James Poulos' Art of Being Free is the kind of self-help book democratic souls really need.

Bertrand de Jouvenel’s Common Good Conservatism

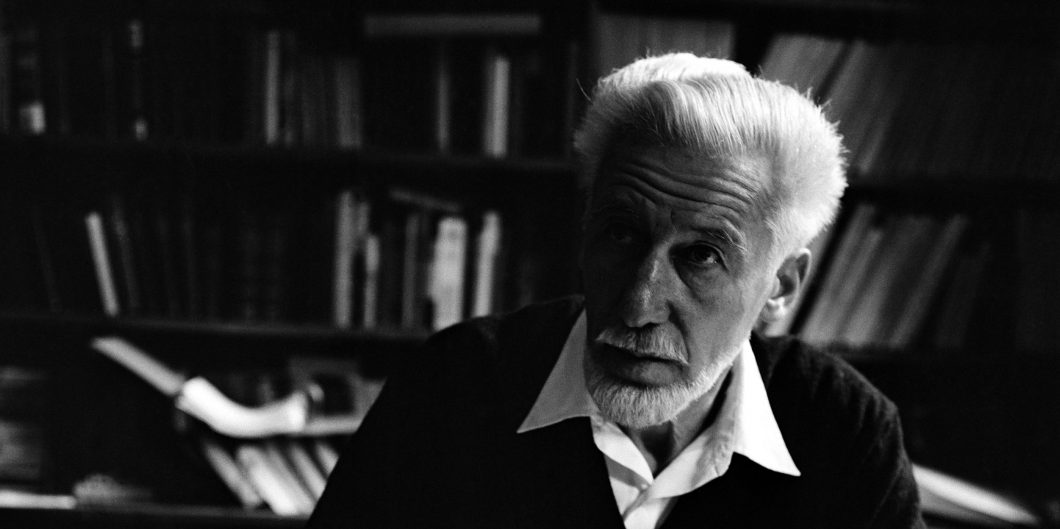

It has been said that Bertrand de Jouvenel (1903-1987) is the least well known of the most significant political philosophers of the 20th century. In many ways, this is perplexing since Jouvenel’s works, in essay or book form, combine erudition, literary grace, and a seemingly effortless capacity for the insightful and memorable aphorism or bon mot. They are as wise and instructive as any contribution to political reflection in recent times. But they are also demanding, precisely because they are free of the terrible simplifications that are increasingly a precondition for getting a hearing in the late modern world.

As Pierre Manent has written, we prefer ideology or the allure of “scientificity” to the “clarity, finesse, and elegance” that inform Jouvenel’s works. There is one additional obstacle pointed out by Manent: Jouvenel’s writings “are sustained and ornamented by a classical culture which is less and less shared.” But if one takes the time to engage Jouvenel’s major works, “at each turn,” Manent points out, one confronts “a view of the historian, a remark of a moralist, a notation of a charming and instructive artist.” Jouvenel’s works of political philosophy, especially On Power: The Natural History of Its Growth (1945 for the original French edition), Sovereignty: An Inquiry into the Political Good (1955 for the original), and The Pure Theory of Politics (1963), which in important respects form a trilogy, are thus a powerful antidote to the spirit of abstraction, and the heavy-handed jargon, that have deformed both modern and late modern politics, and a good deal of recent political reflection.

A Varied Intellectual and Political Itinerary

For a long time, Jouvenel was better known and appreciated as a political philosopher in the Anglo-American world than in France, even as he tended to be misread as merely a particularly erudite classical liberal. This has something to do with the issues raised by Pierre Manent as well as the sheer variation in Jouvenel’s political commitments over a sixty-year period. As his excellent recent biographer Olivier Dard has pointed out, at one time or another Jouvenel belonged, or almost belonged, to every French political family, except the Gaullists and the Communists. A man of the left in his youth, he flirted with the extreme right for a brief period in the late 1930s, convinced that French democracy was decadent beyond repair. But he opposed the Munich Pact and had no illusions about Nazism. The Israeli intellectual historian Zeev Sternhell insisted, wrongly in my view, that Jouvenel was for all intents and purposes a fascist during this period. Jouvenel was famously defended by Raymond Aron during his libel trial against Sternhell in October 1983 (Aron died of a heart attack descending the stairs of the Palais de Justice immediately after his testimony).

Yet on the left, Jean-Paul Sartre’s indefatigable defense of every vile totalitarian regime of the left over a forty-year period (including Stalin’s, Mao’s, and Castro’s) remains uncontroversial in most intellectual and academic quarters. Likewise, Alain Badiou and Slavoj Žižek are applauded even as they write pseudo-philosophical discourses fawning over Mao’s speeches from the murderous Chinese Cultural Revolution, or genuflect before Lenin as the purest of revolutionaries. But somehow Jouvenel’s early political mistakes and misemphases are beyond the pale. An inexcusable double standard persists, one made more noxious because unlike Sartre, Badiou, and Žižek, Jouvenel became a principled anti-totalitarian of the first order.

Jouvenel, for all his philosophical profundity, lacked the surety and solidity of political judgment that marked Raymond Aron, his close friend and the other notable defender of conservative-minded liberalism in France in the decades after WW II. It is worth noting that Aron led the intellectual resistance to the soixante-huitards during the revolutionary rebellion of May 1968 while Jouvenel interrogated his students in a rather naïve pseudo-Socratic way. Yet there can be no doubt that Jouvenel saw through the conceit that “it is forbidden to forbid.”

Firmer Ground

When one turns to Jouvenel’s three masterworks, one turns to much more solid ground, to high political philosophy informed by deep moral seriousness, yet fully attentive to the political stakes of the age. A civilized European in an age of war and tyranny, “having lived through an age rife with political occurrences, [he] saw his material forced” upon him, as he put it at the beginning of The Pure Theory of Politics. Yet Jouvenel recurred to the classics—Aristotle, Thucydides, Plutarch, Shakespeare, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Burke, Tocqueville and Constant—as indispensable guides to understanding modern and contemporary political thought and political activity. His thought is “normative,” that is, committed to inquiring into the nature of the Political Good and a natural “moral harmony,” and its accompanying affections, that must be the aim of any stable and decent political order. At the same time, it is preoccupied with the raw and disruptive political behaviors that need to be understood, controlled and “polished.”

Hence Jouvenel’s oscillation between his never-abandoned judgment that “politics is a moral science,” “a natural science dealing with moral agents” (as he put it in a final chapter added to the English-language edition of Sovereignty in 1957), and his search for an accompanying, if subordinate, “pure theory of politics” that would provisionally bracket the high “moral pulpit” of traditional political philosophy in order to understand “raw” political activity on its own terms. Like the unarmed bishop confronting the barbarians as they are about to sack Rome, normative political philosophy confronts “big men with a cruel laughter.” As Jouvenel puts it, the discipline does its best to teach such barbarians the art of “wise kingship.” At the same time, it tends to moralize the study of political phenomena. This tension between the normative and the behavioral in Jouvenel’s political science is a fruitful one, however. As a result, Jouvenel is a master at resisting the dual temptations of ahistorical moralism and a faux realism that forgets that human beings and citizens are indeed always and everywhere moral agents.

The conclusion is clear: Power is indeed powerless when it eschews justice and the real, if indeterminate claims, of the civic common good. Social and political affections, and rival claims to justice, are much more real than power understood as some self-subsisting good. This is why Jouvenel forthrightly rejects “sovereignty in itself,” a moral, philosophical, and juridical positivism that claims that laws are good simply because they have been promulgated by the sovereign authority. That is pure lawlessness and when carried out to its logical conclusion law loses its soul and “becomes jungle,” as Jouvenel writes in the conclusion of chapter XVI (“Power and Law”) of On Power.

The Pathos of On Power

On Power is Jouvenel’s most famous book. It is at once beautifully written and marked by a deep pathos about the distension of the modern state, the ravaging and egocentric “Minotaur” that is the principal theme of the book. Yet, Jouvenel is a partisan of legitimate authority, a defender of the myriad “social authorities” that resist the aggrandizement of state power and that have a moral integrity all their own. Far from being a 19th century liberal individualist, Jouvenel eloquently takes aim at “individualist rationalism, “a destructive metaphysic” that “refused to see in society anything but the state and the individual.” Jouvenel’s political science constantly reminds us of the affections, the social trust, and the directing social authorities that must “enframe, protect, and control the life of man, thereby obviating and preventing the intervention of Power.”

At the same time, Jouvenel exposed the “legalitarian fiction” that reduced the relation between social authorities, including business enterprises, and subordinates, such as workers, to merely “contractual” relations. The weak and dispossessed will turn to the false and counterproductive solution of a “social protectorate” or a “democratic” or “tutelary despotism” if the strong and privileged do not respect the dual requirements of the civic law and the moral law. The legalitarian fiction begins with a falsely egalitarian premise that all are in effect equal, and elites have no specific moral obligations or responsibilities to the least off or to those in their charge. Genuine inequalities of capacity, status, and social influence persist despite the legal fiction that human relations are equal because they are contractual in character. But this pretense can end up reinforcing a morally obtuse form of oligarchic domination. Jouvenel is both less and more egalitarian than the classical liberals of a dogmatic stripe.

Rather than being a treatise imbued with utilitarian or “rational choice” premises, as some have falsely presupposed, Jouvenel draws widely on classical and Christian wisdom even in On Power. Likewise, in his superb 1952 work, The Ethics of Redistribution, Jouvenel criticizes those who advocate significant government efforts of economic redistribution for a lack of imagination, given their terribly superficial identification of the good life with the indiscriminate satisfaction of human desires. Their policies are not only bound to fail but they reflect a shallow utilitarianism that hardly differs from tradition of political economy they oppose. Moreover, they are not defensible on ethical grounds.

While Jouvenel traces the seemingly inexorable, and deeply troubling and problematic expansion of Power, he knows that this process is fueled and reinforced by a “political Protagorism” where man is “declared ‘the measure of all things’.” Such human self-deification abolishes any measure outside or above the human will, any meaningful and authoritative conception of “a true, or a good, or a just.” We are left with warring opinions of “equal validity.” Political and military force, or civil war by other means, takes the place of rational and civil disputation, however occasionally messy in real life. In place of the City, we once again enter the jungle, or “the state of nature” beloved by the early modern political philosophers.

The Limits of On Power

Jouvenel came to have reservations about his most famous book. He continued to believe that power must be looked at “stereoscopically,” both as a profound moral necessity and as a “potential social menace.” But he came to regret the excessive pathos that informed the book (written in the final years of WW II). In later work, such as the stellar 1965 essay “The Principate,” he continued to warn about deifying Power while giving a more adequate and constructive account of the moral purposes served by public authority. The “barons,” too, he now emphasized, could threaten liberty and social balance. Within a framework of constitutionalism responsive to the specific sociological features of modern society, the public authorities could serve social needs without succumbing to an all-encompassing “social protectorate.”

But “personal rule,” the “principate,” remained anathema to the liberal in Jouvenel. As he wrote in “The Principate,” it is startling that the 20th century experience with ideological despotism did not lead intellectuals and men of letters to massively turn to “constitutionalism,” “to a belief in institutions that limit personal rule.” As Jouvenel wrote in his equally masterful 1965 essay “The Means of Contestation,” deftly examining the Roman tribunate, the parliaments of the French old regime, and the mechanisms of representation at the heart of British liberty, modern men and women must not lose sight of “the dangers of an unlimited imperium.” Jouvenel strikingly adds that peoples who “deify power” are not those who have known freedom.

Reconnecting Liberty, Authority, and the Common Good

Sovereignty (recently republished in France in a new edition for the first time in decades) is Jouvenel’s chef d’oeuvre, a major and enduring work of high political philosophy. It is announced in its early pages as a self-conscious sequel to On Power. In this work, Jouvenel’s liberal, or conservative-liberal, critique of liberalism becomes most evident. In it, Jouvenel speaks much more of authority, legitimate authority, than he does of insatiable, self-aggrandizing Power. The Good, not understood in an a priori way separate from prudence or practical wisdom, comes to sight when any citizen or statesman reflects on what “he hopes to achieve by the exercise of the power which is his.” The fundamental choice facing a human being and citizen is whether to exercise power “despotically by making the good only his own, or will he use it properly in the interest of a good which is in some way common?”, as Jouvenel writes in the opening pages of Sovereignty. This is the deepest “Aristotelian” moment in Jouvenel’s thought. To reinforce his point, Jouvenel cites Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Book 8, 1160B): “The despot is he who pursues his own good.” Radical individualism and despotism share the same perverse premise: There can be no good held in common by human beings. This premise is shared by despots and nihilists alike and can never animate a community of free men and women.

The common good must be lived and theorized outside of the closed city which, in any case, was always more aspiration than political reality. Jouvenel admirably bridges liberal practice and classical wisdom in a way that is unique to his political philosophizing.

Jouvenel’s conservative-minded liberalism takes the notions of authority and the common good very seriously, indeed. Man is “made by cooperation” and human beings invariably live in “social aggregates,” culminating in the City or polity, that depend on social trust, social affection, and a confident affirmation that political authority can and should be exercised for the common good. Authority has two primordial and equally indispensable faces, the Dux and the Rex as Jouvenel calls them: that of leadership and initiative (think Napoleon stirring his morally disheartened soldiers to action and courage at the famous Bridge of Arcola), and good Saint Louis IX of France under the Oak at Vincennes administering justice and thus attenuating social divisions and potential political clashes. Authority has both a “principle of Movement” and a “principle of order,” one that upends the social order and the other that incorporates these changes into a new moral and civic equilibrium, as Jouvenel calls it. While the Dux initiates action, the Rex acts to maintain the social trust at the heart of all enduring political order. Numa and Solomon represent the crucial stabilizing role of authority after the change and conflict initiated by Romulus and David, respectively. The lesson for a liberal order is clear: No society can persist if the initiatives that invariably accompany political and economic freedom are not followed up by the work of the Legislator as peaceful and humane “stabilizer.”

The liberal order is a necessarily dynamic one where initiative should not be stymied by the exercise of heavy-handed state authority. Nor is it a revolutionary order where change can be allowed to war on continuity and settled principle. Jouvenel’s liberalism is thus neither simply conservative nor simply progressive. The more dynamic a society is the more it needs statesmanship to perform the humanizing task of conservative stabilization. Jouvenel does not see Public Authority as “the natural enemy of widespread initiative.” No government should attempt to claim “the monopoly of initiative”—that is always an invitation to tyranny, stagnation, and penury. But government must play a vital role in managing the problems that inevitably arise in a dynamic or progressive society. This should not be confused with “Big Government,” where government is unnecessarily burdened in a way that is “injurious to the performance of its proper duty.”

Bringing Old Gods to a New City

Likewise, it is impossible to think or act politically without reference to the still indispensable notion of the Common Good, the good shared by all within a political community or social aggregate. To resort to the common good is to reject despotism as we have already suggested, a point underappreciated by most soi-disant liberals. But as Wilson Carey McWilliams has so memorably remarked, Jouvenel would bring “old gods to a new city.” “Moral harmony within the city”—the “ruling preoccupation of Plato and Rousseau”—needs to be freed from what Jouvenel strikingly calls “the prison of the corollaries”: its historic identification with small size and population, cultural and social homogeneity, resistance to innovation, and insistence on social immutability. Jouvenel challenges the dogma common to late modern sociology and political philosophy that a society that values individual freedom must repudiate old ideas like the common good and social trust. Even the regime of modern liberty must preserve a sense of community that transcends individual self-assertion. Jouvenel thus resists both rationalist individualism and what he calls “primitivist nostalgia.” The common good must be lived and theorized outside of the closed city which, in any case, was always more aspiration than political reality. Jouvenel admirably bridges liberal practice and classical wisdom in a way that is unique to his political philosophizing.

Jouvenel is most classical and Christian in his profound reflections in Sovereignty on the obligations that belong to man as man. “The famous battle-cry, ‘Man is born free,’” is said to be “the greatest nonsense if it is taken literally as a declaration of original and natural independence.” Men are best understood as dependents, most radically as infants and children, but in truth until each one of us departs the earth. Each of us is “an heir entering on the accumulated heritage of past generations, taking his place in a vastly wealthy association.” It is blindness and folly to proclaim individual or collective self-sufficiency, as Jouvenel makes clear in these passages with their markedly Burkean resonances. Jouvenel sums up his analysis of this matter with an aphoristic insight at once discerning and beautiful: “The wise man knows himself as debtor, and his actions will be inspired by a deep sense of obligation.”

Jouvenel deepens this analysis in the splendid section of The Pure Theory of Politics called “Ego in Otherdom.” There he writes that “social contract theories are views of childless men who must have forgotten their own childhood. Society is not founded like a club.” Jouvenel goes on to praise friendship—and human communion—Martin Buber’s “I and Thou” relationship—as “Man’s greatest boon under the sun.” But in accord with the dialectic of classical and liberal wisdom that defines Jouvenel’s political reflection, he warns us that “the community which arises out of love or friendship cannot be contrived by decree, the intensive emotions which it is proposed to extend wear thin.” Jouvenel adds that the dream of a community of love or friendship in an extensive political community “has proved to generate more hate than harmony.” We are back to the “prison of the corollaries” which must be avoided in thinking about the common good appropriate to the liberal order.

The Fragility and Vulnerability of Politics

The Pure Theory of Politics is the theoretically least successful of Jouvenel’s books in no small part because the conception of “pure politics” that animates it fails to distinguish adequately between political and social relations—both are said to be “just a matter of relations between men.” But politics in the truest and most capacious sense is more than a matter of “how men move men.” That said, this beautifully written book (originally written in English to be delivered as the Storr Lectures at Yale University Law School) is full of insight and stunningly memorable formulations. For example, Jouvenel wisely tells us that “the most immoral of all beliefs is the belief that it can be moral to suspend the operation of all moral beliefs for the sake of one ruling supposedly moral passion. But this precisely is the doctrine which has run throughout the 20th century.” How relevant that insight remains in our new era of ideological passion and justification shows how Jouvenel fully appreciated how morally fanatical political immoralism is.

There is the beautiful passage in the chapter on “The Manner of Politics” that describes Burke’s “violent” reaction to the French Revolution to genuine shock at “the new expressions on faces, the new tone of voices” that emanated from the violent nihilistic French revolutionaries. “When the mob marched to Versailles and carried the Royal family with it by mere pressure of force, when the heads of guards, carried on spears, were kept bobbing up and down at the windows of the Queen’s carriage, this outrage, both to formality and to sensitivity, was one which the deputies dared not condemn, and it is apparent in Burke’s writing that such a scene and its condoning by the assembly swayed him altogether.” How often does eloquence and philosophical and historical insight come together as in this truly inspired passage? The chapter on “The Manner of Politics” teaches the precious rarity, and accompanying fragility and vulnerability, of what Jouvenel calls “mild Politics.”

The Myth of the Solution

Jouvenel ends the third book of his trilogy by discussing “the myth of the solution.” In politics, there are no permanent solutions, only more or less reasonable “settlements.” But, as bitter experience attests, decent and free political “settlements” can always be undone or “unsettled.” Jouvenel thus calls us to be “more effective guardians of civility,” that is, protectors of the manners, affections, trust and liberty that defines a City worthy of human beings. And the French political philosopher hauntingly concludes: “that this is no easy task, an image attests, the head and hands of the great guardian Cicero, nailed to the rostrum” on the orders of Octavius.

It is to Liberty Fund’s enduring credit that the intellectual feast made available by Jouvenel’s three masterworks remain available in English. Jouvenel deepens the liberal tradition with an older wisdom in touch with the deepest wellsprings of the soul, while liberalizing or modernizing classical political philosophy. These works remain a signal contribution to political wisdom in modern times, and a bridge between what is best in classical conservatism and classical liberalism.