Robin celebrates socialism as “freedom from rule by the boss,” but is being ruled by bureaucrats better?

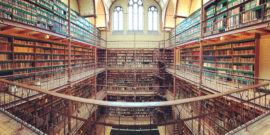

The Decline of Leisure and the Academy

Leisure: The Basis of Culture is certainly an intriguing title. Josef Pieper’s short book is a pair of lectures on leisure and philosophy. That is one topic, not two. Leisure does not mean what you thought it meant.

We live in a world of work. Your life is defined by the work you do. What you think of as leisure is nothing more than a break from work.

Leisure, it must be clearly understood, is a mental and spiritual attitude—it is not simply the result of external factors, it is not the inevitable result of spare time, a holiday, a week-end, or a vacation. It is, in the first place, an attitude of mind, a condition of the soul, and as such, utterly contrary to the ideal of “worker” in each and every one of the three aspects under which it was analyzed: work as activity, as toil, as a social function.

Leisure is equivalent to the act of being a philosopher. The trouble is that we have lost the notion of what it means to be a philosopher by confusing it with the job, the work of being a professor of philosophy. That job is work, not philosophy, and thus not leisure. Philosophy properly defined is the act of transcending the world of work, withdrawing from the things of daily life and experiencing wonder and mystery at the world, asking unanswerable questions seeking wisdom, not knowledge.

Philosophy is, in other words, what used to be called the Liberal Arts, another term that has been stripped of all its meaning in the world of work. Look at any liberal arts college these days and you will see the college proudly trumpeting the usefulness of its degrees. Liberal arts colleges tell us that they will help students find work, will prepare them for a career. Pieper objects.

Aquinas gives this definition: “Only those arts are called liberal or free which are concerned with knowledge; those which are concerned with utilitarian ends that are attained through activity, however, are called servile.” “I know well,” Newman says, “that knowledge may resolve itself into an art, and seminate in a mechanical process and in tangible fruit; but it may also fall back upon that Reason, which informs it, and resolve itself into philosophy. For in one case it is called Useful Knowledge, in the other Liberal.” The liberal arts, then, include all forms of human activity which are an end in themselves; the servile arts are those which have an end beyond themselves, and more precisely an end which consists in a utilitarian result attainable in practice, a practicable result.

So, which do you want to learn? Do you want to learn the useful things that will help you in the world of work? Or do you want to learn the Liberal Arts which will draw you towards having a mind that is free, a mind at Liberty? Sure, you have to work to earn income to pay for the material possessions you desire. Food and shelter are not to be lightly disdained. But, once you have met those biological requirements, do you want your mind to be free or not?

At most institutions, faculty who ask, “What about the liberal arts?” and mean it in Pieper’s sense of the term, survive on life support, and almost nowhere do they thrive.

Do you want your mind to be servile, a dutiful subject of the Nation of Work, offered periodic moments of idleness as a reward for the habitual duties you perform? Or, do you want your mind to be free of the world of work? Do you want to live in a way that work is not the default state, but rather the time that you do the things that need to be done in order to allow your mind to engage in contemplation and wonder? Which is your default state? Is your life work with breaks from work or leisure with times when your mind must devote itself to tasks necessary for survival?

Is there a sphere of human activity, one might even say of human existence, that does not need to be justified by inclusion in a five-year plan and its technical organization? Is there such a thing, or not?

The modern technocrats implicitly assert that such a sphere does not exist. They are wrong. Not everything which is worth knowing only has value because it is useful for practical purposes. Some things, the most important things, are worth knowing precisely because they are not useful, because by knowing these things we get a better glimpse of beauty and truth. This sphere of human existence, not just the fact of its existence but also its content, must be learned somewhere. This sphere used to be what you learned in a liberal arts college.

[L]eisure in Greek is skole, and in Latin scola, the English “school.” The word used to designate the place where we educate and teach is derived form a word which means “leisure.” “School” does not, properly speaking, mean school, but leisure.

The idea of the liberal arts college has been under assault for some time now, not just from without the walls of the Academy. Liberal arts colleges made a Faustian bargain: in exchange for ever increasing tuition payments, we provide students with hypothetically valuable job training in a posh resort.

The result is that there are two forces competing for control of the colleges right now. On the one side, we have the careerism wing, which needs to offer enough practical things to convince parents to part with $70,000 a year in the hopes that the children will get employment paying multiples of that number per year. On the other side, we have the ideologues, who view students as a captive audience for all manner of indoctrination through propaganda. At most institutions, faculty who ask, “What about the liberal arts?” and mean it in Pieper’s sense of the term, survive on life support, and almost nowhere do they thrive.

The point of no return is getting closer. Pieper noted this possibility three quarters of a century ago.

The special sciences, it should be noted, are only free in this sense in so far as they are pursued philosophically. That is actually, as well as historically, the meaning of academic freedom (for academic, in this case, means philosophical or it means nothing); and any claim to academic freedom, in the strict sense of the word, can only arise in so far as “academic” fulfills its philosophical character. And actually, as well as historically, academic freedom goes by the board in exactly the same degree in which the philosophical character of academic studies is lost; in other words, to the extent to which the total claim of the world of work invades the academic sphere.

Once academic freedom goes, there will be no return. Once the voices that ask “Why?” are silenced, the schools will lose all right to call themselves liberal arts colleges. Instead they can be Job Training sites or Indoctrination Camps, but they will no longer be skole, places of leisure and philosophy properly defined. Perhaps this is too optimistic; we are witnessing a steady stream of examples which suggest that academic freedom is already dead in far too many colleges and universities.

But, perhaps in another way this is too pessimistic. The Liberal Arts have been under assault since the time of Aristophanes, and yet the idea survives. This I do know: Pieper is right that leisure is indeed the foundation of culture. To preserve culture, there needs to be people who engage in the act of philosophy. There needs to be people who read books not for the utilitarian knowledge to be gleaned from them, but for the sole purpose of exercising wonder, for the sole purpose of peering a bit more behind the veil, into the dim mirror, shining a bit of light in the darkness.

There is your assignment. Experience real leisure. Set your mind at liberty by allowing it to roam in a world of mystery and wonder.