The influence of law professors like Tribe shows why it is so necessary to confirm justices who will read the Constitution according to its text.

More Than a Carnival

National party conventions have lingered on as a sort of vestigial organ of politics, evolving into something between an industry trade show and a reality TV program.

But even that bread-and-circus aspect will be missing this year, with the parties, to varying degrees, scared away from large gatherings by the coronavirus.

When they return in 2024, conventions are likely to be something different altogether, perhaps ending a run that began in 1831 with the Anti-Masonic Party, the first-ever presidential nominating convention in America.

Although they haven’t mattered as a decision-making body for more than six decades, conventions once made decisions that forged the destiny of the republic, more so even than elections in some cases.

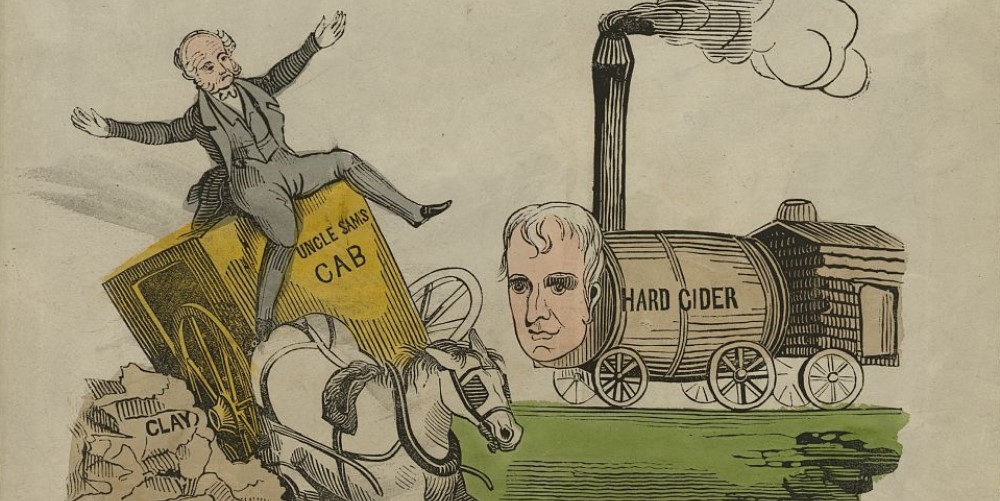

One of those instances was in 1840, an election year famously remembered for the supposed “carnival campaign” of William Henry Harrison and his running mate, John Tyler—Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too.

As Richard J. Ellis explains in scrupulous detail in his new history of that campaign, Old Tip vs. the Sly Fox: The 1840 Election and the Making of a Partisan Nation, there was much more to the contest between the challenger Harrison and the incumbent Martin Van Buren than hard cider and log cabins.

“So often cast as a cautionary tale of how easy it is to hoodwink the credulous American voter with slick packaging of candidates and crude emotional appeals,” Ellis writes, the Whig victory of 1840 was actually “a story less of deluded voters than of rational ones,” although he qualifies “rational” somewhat.

It’s the Economy, Stupid

Old Tip vs. the Sly Fox is the latest entry in the University Press of Kansas’ presidential election series, which is a national treasure. The best volumes in the series are among the finest campaign histories available—elegantly written, voluminously researched, and richly textured.

Ellis’ volume follows in that tradition.

Another tradition of the series is that the authors are fond of debunking the conventional wisdom. The volume on the election of 1824, The One-Party Presidential Contest: Adams, Jackson, and 1824’s Five-Horse Race by Donald J. Ratcliffe, is particularly notable on that score.

Here again, Ellis not only follows the tradition, he exceeds it.

The beauty of this book and of others in the series is that they fully immerse the reader in the campaign, almost making one feel like a participant. That is also the drawback. Almost nothing else about what was going on in the country is touched on. That might be how participants in campaigns feel, but it is not the experience of voters. The lack of context provides something of a blinkered portrait of the proceedings.

Inescapably, though, Ellis does shine a light—in a political context—on the economy, because it had such an effect on the outcome.

A great irony of 1840, Ellis writes, “is that a campaign remembered most for its slogans and songs is the nation’s first presidential election of which it might be said, in the words made famous by Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 campaign, ‘it’s the economy, stupid.’” It’s that legacy, not the myth of a vapid and unserious campaign, that haunts modern political discourse.

Ellis argues that Van Buren was brought down not by clever marketing and silly appeals to ignorant voters, but by the same forces that tend to bring down incumbents of any era. In his case, it was the Panic of 1837, termed by some historians America’s first “Great Depression.”

The economic turmoil unleashed by the Panic had profound and long-lasting implications, not the least of which was the spur it gave to westward expansion. But for Van Buren, the implication was more immediate. Voters wanted to throw the bum out. His conundrum would be recognizable to the modern descendants of his party. After 12 years in power, the supposed party of the people could be fairly painted as having become the elites they once decried, while the supposed party of the elites made a successful appeal to the working class that felt betrayed by elite policies.

The elements of modern campaigning employed successfully by Harrison had been in the works for nearly 20 years—many of them were the brainchild of Van Buren, the father of the Democratic Party.

That helps explain not only the tremendous jump in voter turnout in 1840 but also, just as significantly, the increased turnout in the congressional and state races in the preceding cycle. “Focusing solely on the 1840 presidential campaign . . . exaggerates the effects of the log-cabin campaign on turnout,” Ellis explains, and also “obscures the extent to which the 1840 election transformed the place of presidential elections in American politics.”

Growing out of the increased focus on the executive was the notion that the president is to be held accountable for the economy, even when it is affected by circumstances beyond his control.

Prior to 1840, turnout was consistently higher in state and congressional elections than in presidential elections. This was partly a result of the lack of competitiveness in most presidential elections. But it was also a result of the reality of 19th-century politics. The federal government simply didn’t leave much of a footprint on the lives of most voters, and the executive branch even less so.

Few of the “new voters” of 1840 were actually new voters, Ellis writes. They were simply voters who had typically restricted their interest to local and state matters. Sure, the excitement of the campaign enticed some to vote in the presidential election for the first time. But other factors—the closeness of the race and the bad economy—were at least as important.

The Wisdom of Conventions

Ellis argues that the most important political event took place 11 months before the election.

The Whigs, coming off a respectable showing against Van Buren with multiple candidates in 1836, were confident going into 1840.

The leading luminaries of the party, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, were both pursuing the nomination. Harrison, who had been the leader among the three regional Whig candidates in 1836, was also in the contest. A late entry was another general, Winfield Scott. With Van Buren damaged by the panic and voter fatigue after 12 years of Democratic Party rule, the Whig convention looked to be the defining moment of the campaign.

Anti-Masons and Democrats had held conventions before. But the Anti-Masons never had a chance of electing a president, and the Democratic conventions were mere coronations of a candidate already decided on. The Whig convention of December 1839, Ellis writes, was the first “in which nobody knew beforehand who would become the nominee and in which everybody knew that the nominee could end up becoming the next president of the United States.”

By the time of the convention, the economy had begun to bounce back a bit, altering the political equation. If the depression had persisted and victory had appeared more assured, the party seemed likely to go with its heart, which meant Clay. But a recovering economy meant a tougher fight. In that case, the old hero, Harrison, seemed the better bet. Had the convention been held six months later, when the Democrats held theirs and the economy had begun to spiral downward once again, the outcome might have been different.

Van Buren had to fight the economy and the sense that he simply was not Andrew Jackson. Like almost all election losers, his supporters wanted to blame someone besides their candidate. Usually, that was the ignorant voters. Sen. Thomas Hart Benton saw more sinister forces at work, though. A bitter opponent of the Bank of the United States, Benton later wrote that “two powers were in the field against Mr. Van Buren, each strong within itself, and truly formidable when united—the whole whig party, and the large league of suspended banks, headed by the Bank of the United States—now criminal as well as bankrupt, and making its last struggle for a new national charter in the effort to elect a President friendly to it.”

Seeing the Future

The Bank would not make a renewed appearance for some time, certainly not during the administration of William Henry Harrison. But the debate over it helped shape the emerging partisanship the 1840 election cemented, as Southern Whigs chose to stick with their party rather than yield to the siren song of identity politics. Their Whiggishness overcame their Southerness, the defining moment in the subtitle’s “making of a partisan nation.”

Aside from the partisanship, other aspects of the campaign persist. Certainly, the sloganeering and image-making are part of that heritage. And, contrary to myth, Harrison delivered a number of substantive policy speeches. Van Buren also engaged with voters, although through a letter-writing campaign. This “new business of stumping” was an unprecedented departure from the “mute tribune” standard previously employed by presidential candidates.

But the 1840 election also handed to posterity two other inauspicious developments that plague us to this day, as well as two great lessons that politicians ignore at their own risk.

The campaign—and the presidency that followed—foreshadowed the overweening focus on the executive branch that American politics continues to grapple with. Ellis attributes this shift in focus to the growth of partisanship. With the emergence of the second party system, more voters developed stronger attachments to a political party, which in turn drove increased turnout in presidential election years. It took time for that trend to manifest itself fully in presidential action, partly because Whigs officially eschewed a strong executive. But after the crackup of the Whig Party in the 1850s it was the former Whig, Abraham Lincoln, who accelerated the growth of executive power, necessarily, during the Civil War. By the turn of the 20th century, the progressive movement had begun to institutionalize the idea of a strong and active executive.

Growing out of the increased focus on the executive was the notion that the president is to be held accountable for the economy, even when it is affected by circumstances beyond his control. Ellis notes this in the book’s first endnote, where he qualifies his description of voters as making a rational choice. “Even if voters are not fooled by marketing or rhetoric,” he notes, “a decision rule that reflexively blames or credits the incumbent for economic conditions falls well short of most people’s understanding of rational behavior.” But still we do it, irrationally and unfailingly.

The two great lessons are perhaps more obvious, but only sometimes heeded: Candidates must engage the electorate on the voters’ terms, and nominees should pay close attention to who they select as their vice-presidential candidates.

The myths of the 1840 campaign have hung on, in part, because Harrison’s election itself seems inconsequential in light of his short tenure. But it was Harrison’s death after only a month in office that added to the significance of the outcome. Had Van Buren won, the annexation of Texas would not have taken place when and in the way it did, possibly avoiding war with Mexico and deflecting, at least for a time, the controversy over the extension of slavery into new territory. Had Harrison lived, the same is likely true. Ditto had Clay won the nomination.

Tyler’s ascendancy and his determination to bring Texas into the union set the United States irrevocably on the road to disunion and civil war. Elections—and sometimes conventions—have consequences, even if we can’t see far enough into the future to discern what they might be, or to do anything about them.