A Child's Primer for Liberty

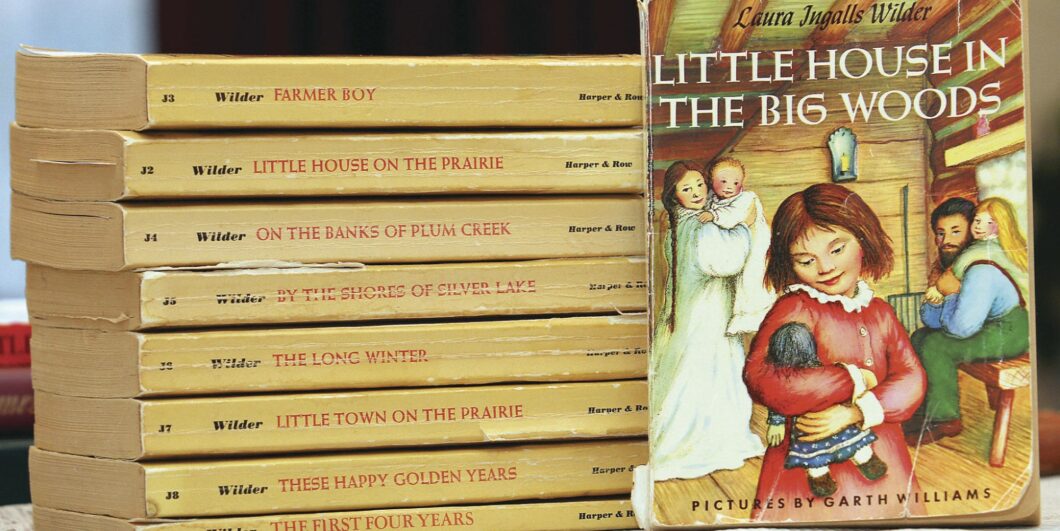

Of all the books my wife and I have read to our now seven-year-old daughter, none has taught as much about life and liberty as the Little House series by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Most literature that enthralls children, like The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, is fantasy, but this series, being a memoir of the Ingalls family when Wilder was growing up, is based in fact—even if softened by a degree of nostalgia with a modified timeline and composite characters. Her family members cannot call on magic but only on their own inner strengths to survive in a world of outer scarcity.

This austere setting makes the series the best introduction for a child to virtues indispensable to liberty—self-reliance, personal responsibility, and respect for individual choice. The difficult life her family led also naturally prompts discussion of how and why our lives have become so much more comfortable today. While these transformations may seem akin to magic, they have been brought about by capitalism—another important lesson for a child.

Unfortunately, political scolds now want to cancel Wilder, not only because her characters do not always reflect modern sensibilities, but because she so clearly sets forth the personal and emotional framework for a society of liberty. If they succeed, they will eliminate a resource that shows how to build a resilient self—the kind necessary to a free society. This story of resilience is particularly timely given the widespread recognition that children today suffer from an emotional fragility that makes it difficult to accept criticism, spring back from reverses, and tolerate arguments on topics essential to democratic deliberation.

From the very first book, Little House in Big Woods, Ingalls remembers her five-year-old self as struggling with self-control. She believes that Mary, her elder sister, is both better behaved and more beautiful, with golden curls compared to her dirty brown locks. Her parents, Ma and Pa, try to keep her within bounds by a combination of love and occasional physical chastisement. Even at this early age, she helps with small chores, like churning butter. The Ingalls family has almost nothing saved. Pa can obtain the fabric for clothes and small treats like candy only by trading the fur of the animals he traps. Still, there is leisure in the evening and plenty of singing with Pa leading on his fiddle. Laura is fascinated in particular by the stories that Pa tells to while away the dark winter nights. Sometimes Laura wants to complain about their hardships but she learns to stop herself and instead contribute to family merriment.

The course of Laura’s childhood recapitulates in miniature the famous thesis of Frederick Jackson Turner about American history, in which the wide-open frontier determined our national character. Pa moves in the hopes of a better life only to move again when those hopes are disappointed. He leaves the little house in the big woods in Wisconsin, because the place is getting overcrowded, no doubt reducing his supply of animal furs. He moves to the plains of Kansas and builds a new house, only to find that the territory belongs to Native Americans. Before the soldiers come to move them off, he takes his family on yet another wagon journey to Plum Creek in Minnesota. There he builds another home, expecting to make a good living through abundant wheat harvests. But hordes of locusts destroy his crops. The scenes of the locusts are brilliantly rendered both when they descend in a glittering cloud to alight on his wheat and when a year later their brood marches off West in the millions having eaten all the surrounding vegetation. Wilder captures both the biblical grandeur and desolation of the events.

Pa then moves his family to South Dakota hoping for a better harvest. But early on, the family faces a winter so terrible that they almost starve. Pa ends up making a living as a clerk who oversees the building and maintenance of the railroad, his change of job presaging the new generations that will move off the farm. Through all of Pa’s many failures, the family receives no support from the government but relies on neighbors and each other. They pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and start all over again.

The series is not a political tract. No one discusses the issues of the day. But it reflects a celebration of individual choice and an acceptance of its consequences without relying on government. Ma Wilder is particularly wary of being indebted to anyone. Apparently, when Laura Ingalls Wilder was younger, she read some theorists of small government like Herbert Spencer. Her daughter, Rose Wilder, who had already become a famous writer herself by the time she helped edit her mother’s books, was one of three women most responsible for the rise of the modern libertarian movement, along with Ayn Rand and Isabel Paterson.

In a nation of self-made men, Wilder is quintessentially the self-made writer, carving out, as from marble, a monument to her family’s life and the wild variety of surrounding nineteenth-century America.

But the ethos of these books is at odds with the valorization of selfishness and atheism that appears in Rand’s novels. The emphasis instead is on solidarity and altruism within the family and without. A neighbor runs to help Ma save their house from a prairie fire that is about to envelop it. At some risk to himself, Pa warns a man of Native American descent that he will likely be killed if he comes to town that night because some of the men working on the railroad are angry he cleaned them out in a card game. Mary becomes blind from scarlet fever and Laura becomes her eyes, describing in detail the beauties of the plains from birds alighting on sloughs to rabbits scattering at daybreak. One of Laura’s happiest moments is when she receives a fur cape and muff for Christmas sent along with many other presents for the frontier settlers from a wealthier church back east. The Bible is a constant comfort in their trials: Locusts were not unknown in the Old Testament.

The books thus illuminate what has become a puzzle for some modern political theorists—how are older theories premised on political liberty, generally called classical liberalism, different from modern ones, often called libertarianism? As Wilder’s book shows, many early celebrations of liberty focused less on abstract political rights but on the moral virtues and duties that create a people who flourish in a society of political liberty. These virtues consist not only of self-reliance and independence, but also personal altruism and neighborliness in a framework where religious observance helps nurture these virtues. Wilder certainly does not idolize the absence of government. She sees the dangers of mob rule on the frontier when railroad workers, apart from family and far from home, terrorize officials to get money that they are not yet owed.

Classical liberalism is a philosophy where liberty is nested in personal virtues of a civic society bigger than politics and the economic market—one likely sustained by religious commitments. Modern libertarianism has become a narrower political philosophy that has grown up in a world where that kind of society and those commitments have steadily dwindled.

Sadly, many fewer children of this generation are likely to read Wilder because of campaigns against her work. Most center on the treatment of Native Americans. It is true that some people in the series baldly state that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” But that is clearly not Wilder’s view. Moreover, Pa, the person she most admires, rejects that claim and is shown saving the life of a man of Indian descent, just as that man probably prevents horse thieves from attacking their wagon. Wilder describes how, in Kansas, an Osage chief shuts down a movement among some of his tribe to attack the settlers. And Laura is troubled by the fact that the settlers moving into the territory have made it impossible for the Native Americans to hunt game as they once did. Yet the Association of American Libraries recently eliminated Laura Ingalls Wilder as the name for its award for an outstanding work of children’s literature to disassociate themselves from the books.

In doing so, they are cutting children off from a valuable lesson. Wilder had very little formal education and what learning she did have was from one-room schoolhouses, supplemented by her mother’s homeschooling and Sunday school. Yet the book is also the portrait of a young girl in the act of creating the woman who would emerge as a skilled author at sixty.

Like James Joyce, she delights in words from an early age. She revels in her father’s gifts as a storyteller. Her sister Mary’s blindness forces her to hone her talents as a succinct lyricist of the natural world so she can fully describe what Mary cannot see. And unlike her other sisters, she always is eager to go outside the home to observe unusual happenings, like the way teams of rough workers labor to smooth the way for the railroad across the swells of the plain. In a nation of self-made men, she is quintessentially the self-made writer, carving out, as from marble, a monument to her family’s life and the wild variety of surrounding nineteenth-century America.

Indeed, she provides perhaps the greatest example for a child of the uses to which liberty can be put, transmuting a series of failed family ventures into something of glorious and enduring value.