A Constitutional Paradise Lost

Mike Lee knows a thing or two about the Constitution. Utah’s junior senator is the son of Rex E. Lee, the founding dean of the law school at Brigham Young University and Ronald Reagan’s first solicitor general. Lee recounts attending his father’s oral arguments at the U.S. Supreme Court, which he characterizes as a somewhat more decorous version of dinner table conversations in the Lee household. The younger Lee went on to graduate from the law school his father helped found, to clerk for Justice Samuel Alito when the latter was on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (later joining Alito again as a clerk at the U.S. Supreme Court), and to specialize in federal appellate court litigation at an elite law firm.

Not many political candidates have launched their careers by trying to work applause lines into lectures on American constitutional history, but for Senator Lee it must have seemed like the natural starting point. A Tea Party favorite, he has commanded the attention of party regulars while joining other young Republicans in putting the idea of constitutional limits front and center.

Now he has tried his hand at getting his message out in book form. Our Lost Constitution: The Willful Subversion of America’s Founding Document articulates some of the core themes of the conservative legal movement. The title echoes what the liberal legal commentator Jeffrey Rosen labelled a decade ago the “Constitution-in-Exile” movement. Rosen warned of an emerging generation of conservative legal activists hoping to revive a long-dead, pre-New Deal constitutional order that would undercut the modern regulatory state. Lee is happy to be counted as a dues-paying member. Like libertarian law professor Randy Barnett, Lee believes that essential components of the U.S. Constitution have been “lost” to judicial subversion and political neglect. In this book, he seeks to describe what has been lost and offer at least some suggestions as to how what has been lost might be recovered.

The book is aimed at the general public. Its author makes no pretense of offering an academic tome defending a particular vision of the Constitution or analyzing in detail how the constitutional rules have been changed over time. He speaks to those who are already convinced that something is wrong with the political system, and he hopes to persuade them to connect their sense of unease to changes that have occurred in our constitutional scheme.

His strategy is somewhat unconventional. Our Lost Constitution is not a jeremiad of the sort that occupied Judge Robert Bork’s later years, but rather a kind of imaginative dramatization of our constitutional history. At the heart of the book are a series of narratives that tell (with “dramatic license,” Lee admits) the story of the creation and eventual abandonment of a set of constitutional principles.

Whether such stories will capture the imagination of a lay audience remains to be seen, but the book does offer an interesting perspective on what are taken to be central constitutional problems of the day. The threat of judicial activism is at most of background interest to Lee, in contrast to Bork and other predecessor conservatives. Unlike John Yoo, Lee has little to say about presidential war powers or the national security state. Unlike Randy Barnett, Lee is not moved by the promise of economic liberty or visions of a properly bounded, night-watchman state. Lee’s preoccupations are his own, reflecting both political debates of the moment and his current perch in the U.S. Congress. His prescriptions are oriented to legislative action and political mobilization, not high constitutional theory.

After a brief introduction that denounces politicians for their unwillingness to make hard choices regarding either public policy or constitutional rules, Lee divides the book into two parts. Part One focuses on “lost clauses.” Each of its five chapters takes up a different constitutional provision, outlining why it was included in the Constitution in the first place and how it was effectively read out of the modern constitutional order.

Covered in turn are: the origination clause (that tax bills must originate in the House of Representatives); the “legislative powers clause” (concerned with the delegation of rulemaking power to administrative agencies); the establishment clause (wherein the author takes a swing at the Warren Court’s “wall of separation between church and state”); the Fourth Amendment (a critique of the National Security Agency’s surveillance programs appears here); and the commerce clause, with that chapter ending rather awkwardly on Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion on Obamacare. In each case, there is copious historical background followed by a brief discussion of a current controversy that implicates the constitutional provision in question.

Part Two takes up the challenge of “reclaiming the lost clauses.” Different avenues for revitalizing forgotten aspects of the Constitution are presented in four chapters that consider generic constitutional questions, without reference to the specific provisions from Part One. The courts lead Part Two but, somewhat oddly, the author mostly cheats here. Rather than considering how or why courts might be a useful vehicle for safeguarding the Constitution, he uses this chapter as an opportunity to tell another set of stories about a constitutional provision: the Second Amendment.

This discussion would seem to fit better in Part One, but it includes an unexpected plot twist. After recounting (one version of) why a right to bear arms made its way into the constitutional text and how the courts gutted the right in the early 20th century, Lee concludes with a redemption story in the form of District of Columbia v. Heller, the 2008 Supreme Court case finding an individual right to possess handguns.

Subsequent chapters suggest actions that Congress could take to help recover the lost Constitution. These mostly amount to stumping for recent legislative proposals—the REINS Act (which would require Congress to vote on significant regulatory proposals), the USA Freedom Act (which would modify the PATRIOT Act), and the move to “defund” Obamacare (which is pitched as constitutionally relevant in that it responds to the President’s administrative finagling with statutory requirements of the Affordable Care Act). The final chapter calls on the people to persuade and mobilize their neighbors to show up at the polls and vote the rascals out. (Needless to say, he doesn’t consider himself one of the rascals.)

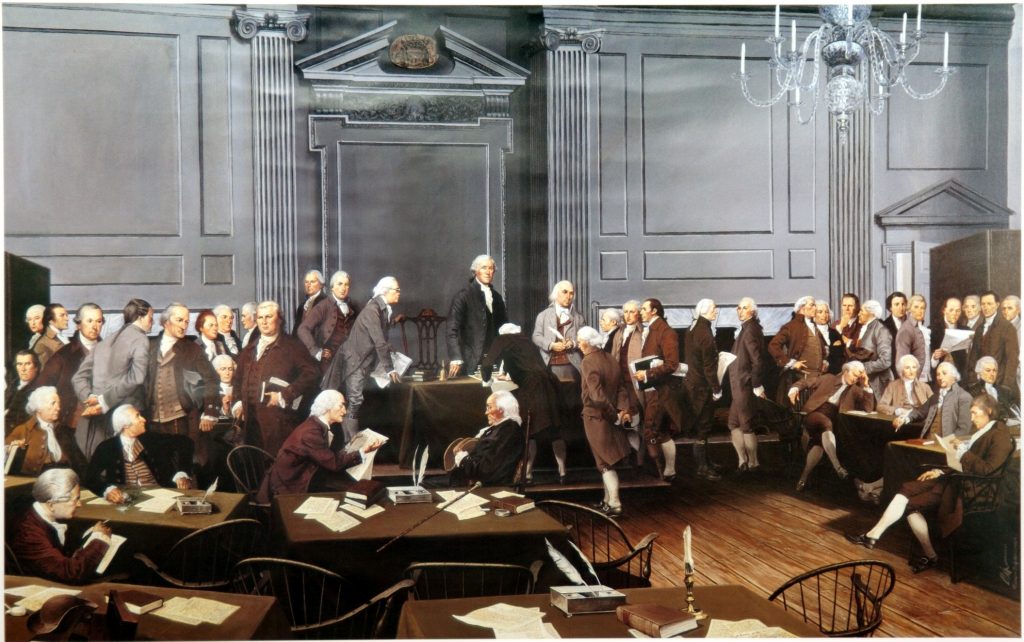

The overarching themes that might have pulled Our Lost Constitution’s individual stories together are not completely evident. In effect, the reader is shown a series of discrete constitutional failures but not a grand vision of American constitutionalism or a coherent diagnosis of the forces that conspire to weaken constitutional safeguards. The problem is most evident in the opening chapter, bearing the grand title, “The Compromise That Saved the Constitutional Convention . . . and That Should Have Saved Us from Obamacare.” Quite a build-up, but the ensuing discussion of the origination clause cannot vindicate the high expectations.

It would be fair to say that the constitutional clause requiring that the House originate tax legislation has been forgotten by most scholars, not to mention most judges and politicians. Lee presents it as having “saved the constitutional convention” because it was part of the Connecticut Compromise that bridged the gap between the rival Virginia and New Jersey plans in the Philadelphia Convention of 1787.

The key component of the compromise was the split in representation between the Senate (giving equal representation to the states) and the House of Representatives (allocating seats by population). Lee mostly ignores that debate, instead placing the origination clause at the heart of the drama. He conveys some sense of why the Founding generation—more precisely, the residents of the large states of the proposed union—would care about this clause, but little sense of why modern Americans should. He brushes past the fact that Congress has long played fast and loose with what is generally regarded as a merely technical (and fairly antiquated) requirement.

The payoff that he offers is that Obamacare was passed through a particularly gross violation of the origination clause. Readers are shown how the Senate’s then-Majority Leader, Harry Reid (D-NV), bypassed the origination clause by stripping the content out of a trivial House tax bill and replacing it with the mammoth Affordable Care Act. The description does offer readers a particularly distasteful look at how the legislative sausage gets made, procedural niceties be damned. But surely the real constitutional objection to Obamacare does not hinge on the origination clause or the fact that the Senate moved first to pass the bill. Lee offers us scant reason to think this clause should be given any more respect by modern legislators than Reid paid it or that more faithful compliance with it would produce better legislative results. It is hard to see how this story could either rally support for lost constitutional principles or persuade the uncertain that they should dislike the Affordable Care Act.

Fortunately, other parts of the book touch on constitutional concerns that are likely to have greater resonance. Lee does a good job, for example, of distilling the recent scholarship that has emphasized the extent to which the establishment clause was designed to be a federalism provision, protecting the states from the possibility of a national religious establishment. He effectively skewers the legal elites of the 20th century who denigrated gun-owners as little better than outlaws. His distaste for feckless politicians who cannot be bothered to take their constitutional responsibilities seriously is palpable and well-taken.

Scholars are unlikely to find this account adequate; the author paints with a broad brush, and the scores he wants to settle are very particular and of the moment. But this is not a book for scholars. It is intended for the potential voters that Senator Lee addresses directly in his final chapter. He hopes to inspire the citizenry to hold their government officials to account and to insist that they recognize and respect the ideal of constitutional limitations.

Hard-won experience and serious political concerns moved the Framers to enact those limitations. Maintaining them requires eternal vigilance and a broad-based fidelity. Ultimately, constitutional preservation must be a popular project. If constitutional rules were made by and for the people, they must also finally be enforced by the people as well. The people could do worse than having Senator Lee in their corner.