A Jane Austen Valentine

Editor’s Note: A condensed and partial version of this article appeared in the Wall Street Journal, November 25, 2021.

Jane Austen’s beautifully scripted and enchanting novels about love and marriage are unrivaled in the canon of western literature. It is one of the ironies of life that she herself never married. But was she ever in love? If so, was that love requited?

Rudyard Kipling thought so. In a delightful poem about “Jane’s Marriage,” he makes the dashing but financially insecure Captain Wentworth of Persuasion stand in for the love of Jane’s life. This is a good choice, since in some respects Persuasion seems biographical. Written in the twilight of her life as she suffered from a debilitating illness, Persuasion is about thwarted love. Austen fans will soon have the opportunity to revisit the streets of Bath with the star-crossed lovers, Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth, as two new film versions of Persuasion are scheduled to be released in 2022.

Some scholars contend that in 1795-96 Jane Austen fell madly in love with an Irishman by the name of Tom Lefroy. Others disagree, claiming that the idea of a romance between Austen and Lefroy is nonsense, the fiction of our own runaway imaginations. Still others say Austen was never in love at all.

Unfortunately, we have little evidence to go on; Jane’s sister Cassandra burned all the correspondence she considered too personal for public consumption. Cassandra seems to have missed a few letters hinting at a romantic interest, however, which have been just enough to fuel the imagination about the man Austen affectionately called “my Irish friend.” If you have seen the film Becoming Jane, with the beautiful and feisty Anne Hathaway as Jane Austen and the incandescently charming James McAvoy as Tom Lefroy, you know the contours of their conjectured romance.

The story, however, is primarily one based on speculation. Here’s what we actually know: Over the Christmas holidays of 1795-96 Jane met Tom Lefroy when he was visiting relatives who lived in Hampshire, near the Austen residence of Steventon. A cheeky flirtation soon developed between the two just-turned twenty-year-olds, so much so that Austen claimed they broke the bonds of eighteenth-century propriety. “Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together,” she wrote Cassandra. Austen considered the young man “very gentlemanlike” and “good-looking,” even picturing him in the role of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, dapper in his white morning coat and slightly comical in heroic consciousness. Tom’s awkward antics and attentions towards Jane earned him the “excessive laughter” of their families and neighbors. If we are to take Austen at her word, within a relatively short period of time the seriousness of the relationship developed to the point that she expected an offer of marriage. Not long thereafter, however, Lefroy returned to London, ending the romantic holiday interlude. The most common story is that the lack of wealth on the part of the lady prompted relatives of Lefroy (probably at the behest of the wealthy uncle who adopted him) to whisk him away from the danger of an imprudent match.

Whether in the form of parlor word games or esoteric writing, the technique of “writing between the lines” has been employed since ancient times.

Was that the end of it? Or did the romance continue? There is certainly speculation that they met again later in London and in Bath. Be that as it may, Tom Lefroy married Mary Paul in 1799. If Jane Austen was in love with him, her heart must have been shattered. Even so, if she loved Tom Lefroy as Anne Elliot loved Captain Wentworth, her love would endure even when all hope was lost.

It was about the time that Austen was finishing up Emma and would soon begin writing Persuasion that her health began to deteriorate. Still, Emma is Austen’s most playful novel, full of midsummer magic and irrepressible wit. Charades, conundrums, riddles, acrostics, anagrams, and shenanigans galore pack the pages of Emma. The title itself is a play (M plus A) on Francis Hutcheson’s theory of moral goodness.

Whether in the form of parlor word games or esoteric writing, the technique of “writing between the lines” has been employed since ancient times. In its more serious form, it has been used for the purpose of hiding sensitive information or radical ideas intended for especially attentive readers rather than the general public. Plato, Shakespeare, DaVinci, Blake, Addison, and many other writers utilized the technique, as did Jane Austen. Some of the most common methods include burying the sensitive matter as far from the beginning and the end as possible; hiding information in acrostics and anagrams; signaling by repetition, contradiction, and incongruities; placing clues and serious truths in the mouths of fools. These techniques require reading with care and a bit of suspicion, often taking the text literally, at least on the first reading, so as not to substitute what one thinks one sees or already knows for what is actually on the page (as was Emma’s wont).

In the ninth chapter of Emma, Austen indicates that the novel is a play on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Highlighting the motto, “the course of true love never did run smooth,” the heroine wryly remarks that “a Hartfield edition of Shakespeare would have a long note on that passage.” Amidst this discussion a charade is left at Hartfield, allegedly dropped there by a fairy, which we are told is a “motto to the chapter” and “a sort of prologue to the play.”

Here is the charade:

To Miss—

CHARADE.

My first displays the wealth and pomp of kings,

Lords of the earth! their luxury and ease.

Another view of man, my second brings,

Behold him there, the monarch of the seas!But ah! united, what reverse we have!

Man’s boasted power and freedom, all are flown;

Lord of the earth and sea, he bends a slave,

And woman, lovely woman, reigns alone.Thy ready wit the word will soon supply,

May its approval beam in that soft eye!

After examining the charade, Harriet immediately begins trying to solve the riddle, offering rather literal guesses such as Neptune, Shark, Trident, and Mermaid. Harriet’s lack of imagination prompts Emma to snatch the paper from her and read it out loud, commanding Harriet to “listen”:

For Miss ———-, read Miss Smith.

My first displays the wealth and pomp of kings,

Lords of the earth! their luxury and ease.That is court.

Another view of man, my second brings;

Behold him there, the monarch of the seas!That is ship;–plain as it can be.–Now for the cream.

But ah! united, (courtship, you know,) what reverse we have!

Man’s boasted power and freedom, all are flown.

Lord of the earth and sea, he bends a slave,

And woman, lovely woman, reigns alone.

Despite Emma’s blithe certainty about “courtship” as the charade’s answer, there is actually a second answer to the word puzzle, which serves as an alternate prologue to the play (that is, dedication to the novel). Invited but really commanded to dedicate Emma to the Prince Regent— an incredibly pompous and profligate man whom she disliked immensely—she mischievously composed this charade with two solutions, the second unspoken one being the “Prince of Whales.” To corroborate this second solution, the first four-line stanza of the charade is an anagrammed acrostic, spelling “lamb,” as in Charles Lamb. Lamb is the author of the scathing poem “Triumph of the Whale,” about none other than the Prince Regent, aka Prince of “Whales.” The second four-line stanza of the charade repeats the “lamb” anagrammed acrostic, verifying the accuracy of the discovery.

Despite Harriet’s more literal guesses, Emma is as sure of the riddle’s solution as she is of its intended recipient.

“To Miss ——–.” Dear me, how clever!” Harriet remarks. “Could it really be meant for me?” “It is a certainty,” Emma replied.

“Such sweet lines!…—these last two last” especially, Harriet cried, disappointed that she could not copy the charade into her album. “Leave out the two last lines,” Emma advised, “and there is no reason why you should not write it into your book.”

“Oh! But those two lines are”–

–“The best of all,” Emma remarked, finishing Harriet’s sentence. Emma continued:

Granted;–for private enjoyment; and for private enjoyment keep them. They are not at all the less written you know, because you divide them. The couplet does not cease to be, nor does its meaning change. But take it away, and all appropriation ceases, and a very pretty gallant charade remains, fit for any collection. Depend upon it, he would not like to have his charade slighted, much better than his passion.

According to Emma, then, separating the couplet (couple?) from previous lines does not diminish the message of love, or the love itself. What does change, however, is the “appropriation.” These last two lines are private—too personal to share with the public; they indicate to whom the charade is addressed and thus the object of the author’s romantic intentions. The lines are also part of the proclaimed prologue (i.e., dedication) to the novel. But just as we know that the intended recipient of the charade is not really Harriet, perhaps the intended dedicatee of the novel is not actually the Prince Regent.

In sum, for the curious and perhaps suspicious reader, all of Emma’s commands to omit the couplet and let it remain a private matter amount to a definitive hint to pay attention to it. Here it is again:

Thy ready wit the word will soon supply,

May its approval beam in that soft eye!

These prosaic lines hardly seem worth the exercise of ready wit. But what if we apply to them the techniques we used in respect to the first eight lines? Let us also attend to any incongruities in the note the fairy dropped, and to repetition in regard to the command to leave out the “last two” or “two last.”

If you examine these lines for acrostics, including simple acrostics (letter at the beginning), telestichs (letter at the end), and mesostichs (letter in the middle), you have the following letters:

TOYMEE

Now, leave off the “last two,” i.e., in this case not the whole two lines but the last letter in each of these two lines, thereby omitting “y” and “e” and taking “l” and “y” as the telestichs letters. Now you have the following letters:

TOLMEY

Finally, to whom is this charade addressed? As reproduced in the text, without any interpretation by a character, it is addressed “To Miss —” This same salutation is repeated by Harriet during the course of the conversation: “‘To Miss ——–.’ Dear me, how clever!”

However, when Emma reads the charade out loud to Harriet—annoyed with Harriet’s inability to immediately grasp “courtship” as the answer—Emma’s impatience results in carelessness, causing her to misread the salutation. Instead of “To Miss —“, she erroneously says “For Miss —”, commanding Harriet (and us) to “listen.”

One of the common methods used in the art of esoteric writing is apparent error, contradiction, and incongruity. “For” is a spoken error by Emma, but deliberate on Austen’s part. It is inconsistent with the written charade. Accordingly, let us add the three letters of the mistakenly spoken word (“for”) to the other letters we have gathered:

TOLMEYFOR

Now, anagram these letters, and what do you have?

Jane Austen died at the age of 41, carrying in her heart a love so deep and enduring that it continued to burn even when the embers of hope had longed turned cold and ashen.

Yes, indeed. Jane Austen’s Irish friend. Her love for Tom Lefroy was a secret she could not, finally, take to her grave. The discovery of the message of love Austen encoded in this novel about love that “never did run smooth,” is stunning, breathtaking, and heartbreaking. There can be little doubt that Jane Austen knew love, or the name of the man she loved. There really should never have been uncertainty about the former, for no one could write such perfectly exquisite and beautiful portraits of the marriage of true minds without herself having experienced that love, even if that experience was thwarted by everything but the most inscrutable of love’s attendants: hope. Hope, even when all hope is gone.

For those readers not familiar with the intricate art of esoteric writing, or those who have already decided that Austen never loved Lefroy (nor he her), the discovery of, admittedly, a rather complicated triple acrostic combined with a seemingly trivial error in the text may well be unconvincing. Granted, it would be more persuasive if Austen had provided confirmation that the finding is correct, as she did in the case of the “lamb” anagrammed acrostic in chapter nine, repeating it so as to leave no doubt that it was intentional on her part, not a matter of chance.

If I am correct, both the Prince and Tom Lefroy are named in the charade that constitutes a prologue to the play, indicating two dedicatees of the novel. One of the dedicatees, however, was the object of her ridicule and the other of her love. It seems a pity she had to give actual front-page billing to the one she despised rather than the one she adored.

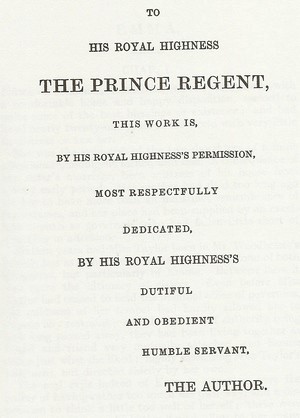

But never underestimate Jane Austen. If you are an avid reader of Austen’s works, you have probably seen the Emma dedicatory page dozens of times. But have you really looked at it carefully? The formatting is odd, seemingly random. All the lines are centered until you get to the last three lines, minus the signatory. These lines are not left justified, right justified, or centered.

Is the formatting of these valedictory lines merely haphazard, or is there a method in the author’s madness? Let me again suggest that we apply the technique of reading (vertically) between the lines that we employed in the chapter nine charade. Might the seemingly random arrangement of these three lines reveal the intentional alignment of certain letters (as much as early nineteenth-century typesetting could achieve!)? Can you see these letters? Can you see that they spell the name of Austen’s “Irish friend”?

Jane Austen died at the age of 41, carrying in her heart a love so deep and enduring that it continued to burn even when the embers of hope had longed turned cold and ashen. But as was her wont, rather than dwell on misery, she chose “to remember the good things rather than the bad.” Kipling may have learned this lesson from Jane Austen; his poem about her ends as all of her novels do: in happiness deserved.

In Kipling’s account, upon entering Paradise, Jane was met by three Archangels who offered any of heaven’s gifts she wished to command. “Jane said: ‘Love.’” Instantly the seraphim set forth in search, whispering “round the Nebulae” — “Who loved Jane?” “In a private limbo where none had thought to look, sat a Hampshire gentleman reading of a book.” The book “was called Persuasion,” and in its pages told, the story of their love, timeless, and richer than gold.

Happy Valentine’s Day!