In oral arguments, the justices asked the tough questions about "race-conscious" admissions.

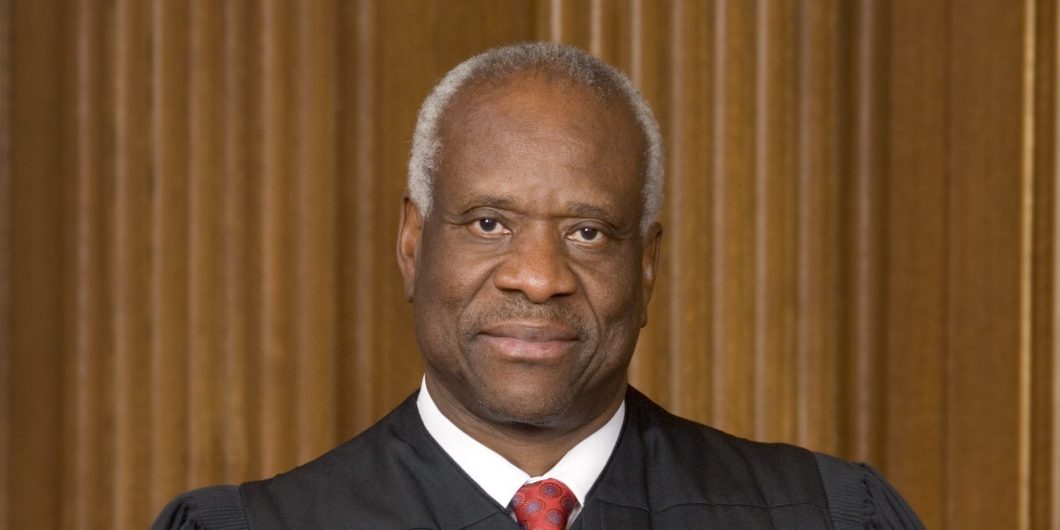

A Justice for All Seasons

This month Clarence Thomas will have been a Supreme Court justice for thirty years. He has been a dauntless originalist on the Court and in many ways both bolder and more consistent than Antonin Scalia. Thomas has staked out originalist positions in scores of opinions of increasing sophistication and breadth. Indeed, there now are few areas of constitutional law on which he has not left directions about recovering the original meaning of our fundamental law.

To be sure, most of these opinions are either in dissent or in concurrence. But because of his consistency, longevity, and courage in the face of constant criticism, he is now poised to become more influential. He is joined by other originalists, Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, with Brett Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito also moving toward an embrace of originalism. And it is, in any event, a mistake to measure the influence of a justice only by his short-term impact on the decisions of the day. Justices, like Oliver Wendell Holmes, have set out dissenting constitutional visions that have resonated decades after they have departed. Such will be the destiny of Clarence Thomas if more originalist appointments are made. He may be seen as a prophet with honor in the future just as the great nineteenth-century dissenter John Marshall Harlan was seen in the twentieth.

Bold Beginnings

It is often said that justices need at least five years to find their voice on the Court, but one of the remarkable features of Thomas’s service was that he offered strong, if simple, originalist arguments very early in his tenure. His dissent in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton and concurrence in United States v. Lopez are works of a jurist already sure of his mind.

Thornton turned on whether the states could preclude individuals who had served a certain number of terms as a senator or representative from again appearing on the ballot for that office. The majority opinion in Thornton rested on the claim that the qualifications set out for these offices in the Constitution, like minimum age, were exclusive. It thus held that term limits were unconstitutional because state law could not add qualifications relating to the number of terms a candidate had previously served. The majority asserted that its view was supported by the precedent of Powell v. McCormick, in which the Court held that Congress could not exclude Rep. Adam Clayton Powell on the basis of criteria not mentioned in the Constitution’s Qualifications Clause. The majority also argued that additional qualifications would detract from national sovereignty established by the Constitution.

But Thomas observed that the Tenth Amendment was expressly designed to rebut inferences like the one the majority attempted to draw from the Qualifications Clause. Because the Constitution simply provides a set of minimal qualifications for representatives and senators, the Tenth Amendment’s reservation of authority shows that the states are free to make additions as long as they are not forbidden by the Constitution. Powell v. McCormick was right because Congress lacks an enumerated power to impose additional qualifications, but nothing in the Constitution forces states to surrender that power.

In United States v. Lopez, Thomas wrote a concurrence that was the most interesting judicial explication of the Commerce Clause in more than half a century. He reconsidered the “substantial effects on interstate commerce” test because it was inconsistent with the original meaning of the Commerce Clause. First, Thomas showed that the modern test used a meaning of “commerce” that encompassed all economic activity, whereas the meaning of “commerce” at the time of the Framing was limited to trading and exchange, as distinct from other productive activities such as manufacturing and farming. Second, Thomas observed that permitting Congress to regulate all activities “affecting” interstate commerce deprives many of the other clauses in Article I, sec. 8 of independent force. Why give Congress particular authority to regulate bankruptcy, since insolvency self-evidently affects economic activity among the states?

No justice has ever announced his jurisprudential stance more quickly or forcefully than Justice Thomas.

An Increasingly Sophisticated Body of Work

Over the years, Thomas has continued to write powerful originalist opinions, now approximately 150 in total. And no justice has ever written more to provide a comprehensive map of what the Constitution would look like if interpreted according to its original meaning.

Thomas has been equally active in interpreting the originalist Constitution of 1789 and its amendments. For the Constitution of 1789, he has written opinions about the original meaning of the vesting of legislative, executive, and judicial power; on the Commerce Clause; on the Treaty Power; and on the Census and Ex Post Facto Clauses. He has written on the First, Second, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Tenth Amendments. He has also explored the Fourteenth Amendment, arguing in particular for the revival of the Privileges or Immunities Clause that was wrongly interred by the nineteenth-century Slaughter-House Cases.

No other justice approaches the breadth and comprehensiveness of Thomas’s investigation of the meaning of our fundamental law.

Thomas’s analysis has grown more sophisticated as he gained more experience in originalism. He now often carefully understands the text in its legal context to draw fine distinctions. For instance, he has joined Justice Scalia in construing the Confrontation Clause right to reflect its meaning at common law, ruling out many hearsay exceptions to the right. But he also argued that the scope of the materials subject to the Confrontation Clause must be understood through their legal context in England. As a result, he departs from Scalia by restricting the Clause’s scope to materials that have been provided with the requisite “solemnity” that prior law reflected.

Thomas’s sophistication is also reflected in his appetite for addressing the fundamental questions that haunt originalism such as its relation to precedent. In Gamble v. United States, Thomas rejects stare decisis for both constitutional cases except in instances where the precedent is not “demonstrably erroneous.” Thomas recognizes that judges in England at the time of the Constitution applied a more robust doctrine of stare decisis, but rejects the notion that federal judges have authority to follow a similar doctrine in today’s statutory and constitutional cases. Thomas argues that “we operate in a system of written law in which courts, [unlike common law courts], need not—and generally cannot—articulate the law in the first instance.” One does not have to fully agree with Thomas on this point (and we do not), as we do not necessarily agree with some of his other originalist interpretations to recognize that he alone among the justices is making a serious effort to integrate originalism with stare decisis.

His opinions have also shown a willingness—perhaps an increased willingness over time—to follow originalism in divergent ideological directions, demonstrating how originalism is orthogonal to present political concerns. Sometimes his opinions are more conservative than those of the Court and his fellow originalists. An example is Carpenter v. United States, where Thomas in a lone dissent insisted that the Fourth Amendment’s original meaning precluded only searches into the property of the person claiming the protection of the right—and that a company’s records were not plaintiff’s property and therefore fell outside the Amendment’s “persons, houses, papers, and effects.”

At other times, especially recently, his opinions have been joined by the more liberal members of the Court on originalist grounds. Last term, for instance, in the major standing case of TransUnion v. Ramirez, Thomas wrote the main dissent and was joined by justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor. Relying on historical materials such as William Blackstone’s Treatise, he argued that individuals asserting private rights did not have to allege actual damages. Thus, entertaining such suits was not beyond the judicial power of Article III.

In United States v. Arthrex, Thomas led the same group of justices in rejecting a challenge to the status of administrative patent judges on the grounds that they could not be inferior officers if their decisions were unreviewable. He noted that inferior officers had unreviewable authority in the early republic, and argued that there was no reason to believe that the Constitution distinguished between the different types of powers exercised by inferior and principal officers.

Given that he has been on the bench for thirty years, it is not surprising that he has sometimes missed the mark. At times, for instance, he has failed fully to address some serious arguments against his position based on original meaning. For instance, some have argued that the federal government’s aid to the newly freed slaves suggests that race-conscious aid by states is constitutional today. While one of us has provided evidence against this claim, it deserves an extended originalist rebuttal in the United States reports.

But it should be noted that Thomas often has a plausible rationale when he does not investigate the original meaning and instead tries to make the best that can be made of current doctrine. He believes that the constitutional issues must be raised by the litigants themselves so that the matter can be addressed in an orderly way. Litigants often have tactical reasons for not making certain claims. It would not advance the orderly and deliberative process of legal interpretation for judges themselves to employ their own jurisprudence to initiate a spring cleaning of constitutional law in every case.

Outrageous Criticism

Thomas has done all this work while suffering the most unfair criticism of any Supreme Court justice for decades. In his early years on the Court, those deprecating his intelligence dismissed him as a clone of Scalia. But as is clear from the discussion above, he disagreed with Scalia in some important respects. Moreover, scholars have suggested that Thomas’s more consistent originalism had an influence on Scalia, moving the latter from his own “faint hearted originalism.”

Thomas was then ridiculed for not speaking at oral arguments and his explanation—that he wanted to give advocates more speaking time in what had often become a free-for-all of aggressive and disjointed questioning—was dismissed as an attempt to hide his intellectual inadequacy. But when the Court moved to seriatim questioning during the pandemic, not only were his questions searching and pointed, but his themes were often picked up by his colleagues. Sadly, Thomas has had to suffer unfair criticisms of his intelligence by those who never would have raised such criticism if Thomas were more politically correct.

He was also attacked for opposing affirmative action on the assumption that he benefited from such programs. But even if the assumption were true, how can a past benefit ever purchase one’s current conscience and dictate one’s current legal duty?

More generally, Thomas has been attacked because he does not vote as others think an African American should. This kind of criticism puts the lie to many left advocates of “diversity.” What they want is not more minorities in positions of political power, but more people who will move the nation leftward. In a world where those who held important offices were truly valued for their diversity, Clarence Thomas would be treated as one of the most important figures in the history of African American progress. Indeed, except during Barack Obama’s presidency, Clarence Thomas has been the highest ranking minority official in the United States Government. Yet he was initially all but ignored by the National Museum of African American History. And Amazon pulled a documentary about him from their video collection during Black History Month.

Historical ratings of justices, like historical ratings of presidents, are controversial because it is difficult, if not impossible, to evaluate a justice without deciding on a metric of jurisprudence, and the correct jurisprudence remains a matter of great dispute. But for formalists, including originalists, Clarence Thomas has a claim to be the greatest justice of all time. No other justice approaches the breadth and comprehensiveness of his investigation of the meaning of our fundamental law. He has pursued this ideal of justice without being deterred by much scurrilous criticism. A justice for all seasons must have sound convictions and the courage to follow them. Clarence Thomas has both.