A Yellow Journalist's Tale

In The Crowded Hour: Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and the Dawn of the American Century, Clay Risen has written a rollicking, entertaining, colorful interpretive essay on the Spanish-American War focusing on Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders and their part in the invasion of Cuba and the liberation of Santiago, Cuba. He begins his tale with an interpretation of the national soul from the perspective of the New York celebration of victory a year after the war. In a grandiose assertion, he explains that “[t]he celebration was less about the nation’s recent past achievements than what those achievements foretold: a new, confident, global American Empire.” Quickly after his grandiose assertion, though, he explains that this “book is an account of their [the Rough Riders] story, and Roosevelt’s story with them. It is also an account of the Spanish-American War: why it happened when it did, and how it shaped America at a crucial moment in its history.” A rather more limited scope than a “new, confident, global American Empire.”

To avoid being misinterpreted himself, he telegraphs his interpretive bona fides, to ensure that we understand this is no attempt to let the age and its characters speak for themselves, but is rather to be a critical analysis, wherein this empire aborning is establishing within itself an “apartheid regime” in the south, and building itself upon a “campaign of outright annihilation against Native Americans.” He is, to say the least, an unlikely candidate to write a book like The Crowded Hour with focus on the foreign policy and military subjects. He has several books to his credit on topics ranging from Scottish single malt whisky and American whiskey, bourbon, and rye to historical treatments dealing with the Civil Rights Act and the aftermath of the Martin Luther King assassination. Apart from the obvious effort at revisionism, it remains curious why a noted historian of various whiskies would turn to an historical treatment of the Spanish-American War and the Rough Riders in particular—or should claim the expertise to undertake such a study.

Still, he asserts, “two facts about America’s place in the world stood clear” at the time: 1) “global economic power requires comparable Military power to protect it”, and 2) this power should do more than protect mere material interests, but rather represent the idea of America, its, as he calls them, “universal values written into its founding documents, ideas about liberty and equality.” There is a tension in these two facts that the Rough Riders and Theodore Roosevelt will at least emblematically reconcile in their participation in the Spanish-American War and lay a foundation for future American interventions to come. Risen later refers to these as templates for American action that become routinely and rather automatically and unreflectively applied in the 20th century.

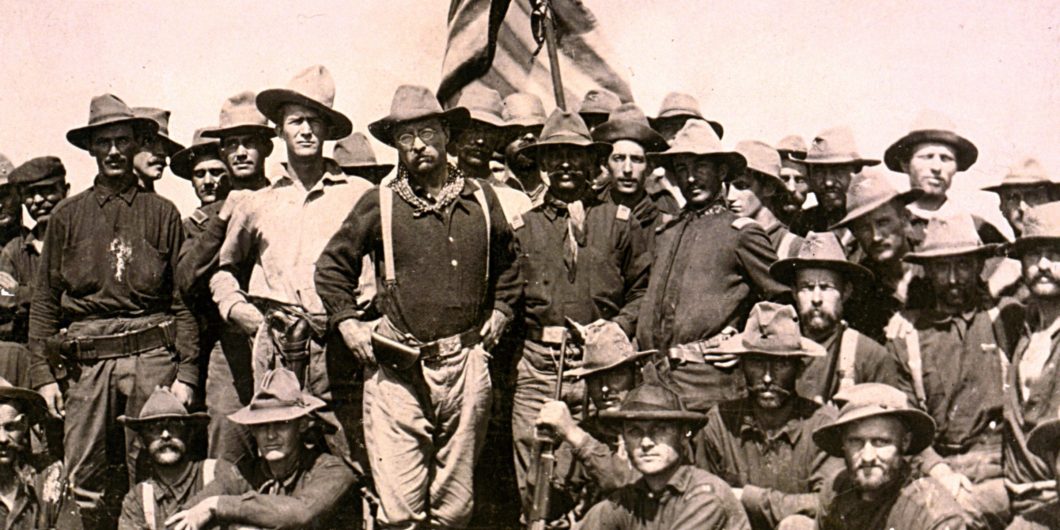

After a chapter devoted to a brief and conventional recounting of Roosevelt’s biography, Risen lines out the progress of the story in chronological succession from the Spanish early conquest in Cuba to the push for American intervention and the final commitment to war. The focus then turns to the Rough Riders, the First United States Volunteer Cavalry, their organization, training, transit to Tampa for embarkation, and then their successive experiences in the execution of the landings in Cuba, the ensuing battles, the liberation of Santiago, mustering the Rough Riders out of the Army after less than six months service, and some post-war wrap-up.

The Crowded Hour is extravagantly sourced. Risen has quite obviously scoured the secondary and journal literature for material on the Spanish-American War. Still, one is left with the impression that one reason the war is typically treated in larger histories or collections is due to the paucity of compelling detail to be found. One finds a myriad of filling details such as the breathless description of the correspondent Richard Harding Davis’s stunning good looks, and accounts of the after hours exploits of the Rough Riders in San Antonio among the drinking and carousing establishments of the town for example, instead of the telling detail that illuminates the core elements of the story. The account is rich with descriptive detail of the flora and fauna of Cuba, as well as the primitive or colorful characters of the towns the Americans encounter on the island.

Risen does an outstanding job of describing the condition of the US Army in 1898 and its unpreparedness for executing an expeditionary landing in force against territory held and defended by a European army. He rightly makes much of this incapacity, particularly as he recounts the manifold difficulties experienced by the Rough Riders in their transit to the Tampa embarkation port, the embarkation itself, and the transit to and landing in Cuba.

Risen likewise provides a very colorful and readable account of the expeditionary landings in Cuba and the battles that follow, leading to the surrender of the city of Santiago. He catalogs the Spanish mistakes that worked to offset the mistakes and poor preparation of the American forces. The initial battle at Las Guasimas is well described by Risen and is one of the few displays of initiative by leadership during the American campaign. Risen provides rich and colorful description of the scene and setting, as well as the action, particularly focusing on the individual instances of death, insofar as those details are available. Risen observes, in recounting the success of the Rough Riders in maintaining unit integrity and discipline under fire, “[a]dd to that the triple-digit temperatures, the strange surroundings, and the seemingly invisible enemy, and their feat becomes even more impressive.”

Here we begin to glimpse the deficiencies of Risen’s capacity for analysis on the subject of war. As long as the challenge is merely descriptive in nature he is fine. But his focus on celebrity colors his perception. It is presumptuous to expect even green invasion troops should expect to meet the enemy in temperate conditions, intimate surroundings, and with the enemy staged in the open for the shooting. It was the very intent in standing up a cowboy regiment to mitigate these very factors by choosing men hardened by the elements and life, and capable of handling the unusual and unexpected. Further, we have no means to gauge the comparative performance of the Rough Riders since Risen excludes discussion of the actions of the main force advancing directly up the road to Las Guasimas, save a brief acknowledgement that the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Regiment held the line allowing Roosevelt, dispatched by Wood, to restore order to the disarray in the right side of the Rough Rider line. This they apparently did in the same triple digit temperatures, in unfamiliar territory, and against an unseen enemy.

The same travelogue level of filling detail is brought to bear on the seven days between the battle of Las Guasimas and the assaults upon El Caney and the San Juan heights overlooking Santiago, as the troops of the expeditionary force are collected and supplied for the assault. Risen then supplies a creditable and colorful description of the assault itself, and for a change expands his view beyond the Rough Riders to the assault on El Caney as well. The narrative flow of Risen’s over-interpreted tale falters a bit when he includes the action against El Caney by the 1st Division, made up of eight regular and one volunteer regiments, which falters and requires most of the day to reduce the fortified position held by disciplined troops. Here we do not see American “gumption and guts“ compensating “for a lack of formal military training,” but rather disciplined and trained Americans fighting to victory.

The problem with focusing so exclusively on the celebrity Rough Riders is compounded when one reviews the table of organization for the Corps as a whole. Of twenty-four regiments organized in three divisions, two of infantry and one dismounted cavalry, we find that only three of the twenty-four are Volunteer Regiments: the Rough Riders, the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, and the 71st New York Volunteer Infantry. These other volunteer regiments are unimportant to the story, for in Risen’s view, it is the Rough Riders who established the template for “intervene first, ask questions later” that defines American action in the 20th century: “The Rough Riders set the template for how Americans would regard their military, and their militarism; the Spanish-American War set the template for how Americans would go out into the world in search of monsters to destroy.”

This seems like a curious claim. Consider that we find also in the table of organization that all four of the Regular Army’s black regiments are included: the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments, and the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments. Yet Risen finds only the 10th Cavalry worthy of any significant mention, and always in the most palpably condescending ways as the segregated or colored unit. These are storied units with exemplary records of discipline in the Army of the time. But one might ask: Were these professional soldiers not also templates for American militarism and adventurism? Were not any of the regulars?

As much as Risen emphasizes the Jacksonian character of the Rough Riders, applying gumption and guts in lieu of formal training, etc., he utterly fails to understand the profound accomplishment of Theodore Roosevelt in the assault on San Juan heights—one that belatedly (in 2001) saw him awarded the Medal of Honor. Whether consciously or not, Roosevelt either saw and took, or just took an opportunity to rally not only his own regiment, but the elements of other regiments scattered across the hillside in his vicinity and by force of will, personality, cajoling, and prodding he and those he led took the first height that day, then turned and supported the neighboring assault on San Juan Hill itself. This was a staggering military feat of leadership and deserves to be so recognized. Roosevelt may have been a shameless self-promoter and a jingo, but on that day, he demonstrated he was also a military leader of substance.

Risen calls his pre-war writings vacuous, one of his many silly and ignorant formulations. Far from being vacuous, those writing represented both the learning and the character of the man who led the charge up Kettle Hill. Roosevelt’s crowded hour was a lifetime in preparation, not a sudden event found only in the crucible of war. Here Risen follows Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris who asserted: “Ninety-nine percent of the millions of words he thus poured out are sterile, banal, and so droningly repetitive as to defeat the most dedicated researcher.” Yet since at least the mid-1990s, dedicated researchers in both the popular and academic worlds have found a rich store of material for serious analysis. Perhaps most notable is the fine volume by Jean Yarbrough on Theodore Roosevelt and the American Political Tradition. One would be well advised to consider the ten pages or so that Yarbrough dedicates to the period of the Spanish-American War as a thoughtful antidote to Risen’s treatment of the war, Roosevelt, the Rough Riders, and American political principles in general.

In the final chapter of the book, Risen takes a single speech by William McKinley, combined with the Rough Riders’ “templates,” and extrapolates from the Spanish-American War to all the wars of the 20th century that America engaged in, even to Iraq. How he gets there is mysterious, for there is no formal explanation of how the Spanish-American War, that war of the small, woefully unprepared, unorganized, ill-supplied Army led by overweight, gout-afflicted leadership that did not plan, reconnoiter, or lead, provides the template for Iraq in 1991 or 2003.

In the context of America’s armed forces today, it is easy to forget that in 1933, Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur declined a German invitation to a military exercise. As William Manchester recounts in American Caesar

His refusal reflected, not disapproval of the new regime in Berlin, but a dawning understanding of the humiliating explanation for his welcome in foreign capitals. While appreciative of the Unite States’ war potential, and thus eager to court its goodwill, other nations knew that they had nothing to fear from its military establishment. MacArthur led the sixteenth largest army in the world.

Some template, some militarism, some empire. Risen’s attempt at a progressive revisionist interpretation of the Spanish-American War falters on the shoals of actual history.