Destroy customary norms of neutrality and hark how social discord follows.

Abortion and the Arts

In the fall of 2018, The Progressive magazine ran an article: “The Mark Judge We Knew.” The piece highlighted some articles I had written for The Progressive, the editors noting that in the 1980s, when the pieces ran, I “took a firm stand on the political left.” The headline offered this summation: “Writing for us back in the 1980s Judge… displayed a concern for social justice, and a progressive vision for the world.”

Looking back on what I wrote for The Progressive more than three decades ago, I was struck not by how much my thinking has changed, but rather by how consistent it has been. Back then I was against censorship and adored the arts and pop culture as life-affirming and freedom-loving signs of creative power. I thought that most conservatives didn’t appreciate, support, or understand art, something that I think is still true today (although my feelings about it may not be as harsh as they were in my socialist college days). Back in the Reagan years, however, there was one thing that kept me from fully embracing liberalism. That thing was abortion.

I grew up in an artistic, intellectual, tolerant, funny, and loving Irish-Catholic family. We love literature, movies, poetry, plays, and the visual arts. There was only one thing that separated us from our fellow liberals: the life issue. We were not holy rollers about it, but my father was very clear where he stood. I still remember the nights when, with guests around the dinner table or on the back porch, things would turn silent or angry when the question of abortion came up. My father, a brilliant, mystical Catholic who worked for National Geographic and had an encyclopedic knowledge of books and big band music, would be happily partaking in a free-flowing conversation about the latest novel, song or hit movie, or politics, when someone, usually one of his children’s friends, would mention abortion. Up until then, our friend probably got lulled into thinking they were in a safe space; after all, dad disliked Reagan’s policies, was a globe-trotting journalist with a ribald sense of humor, smoked, drank, loved football and Glenn Miller.

When our friends railed against those crazy right-wingers who were against abortion, dad would stun them. “That’s a baby,” he would quietly say. “You can’t argue with the science.” Things would grow quiet, then tense. There would be counter-arguments tossed out, but dad would not budge. He would softly explain the science of conception, talk about sonograms, and mention scientists he had interviewed for National Geographic. He was not some yahoo at a tent revival meeting. This was, he softly said, fact. Our guest would be shocked: but, but, your dad is so cool. Well, yes. Our dad is a pro-life, anti-communist John F. Kennedy liberal. There used to be a lot of them. The late theologian Richard John Neuhaus summarized my father’s philosophy well. When asked how he could support Vietnamese refugees and the poor in the 1960s, and the unborn in the 1980s, Neuhaus responded, “because it’s the same fight.” The reason The Progressive magazine was remembering me in 2018 was that I had become a target for the left, who tried to use me to bring down a nominee for the Supreme Court. They did that out of fear that Roe v. Wade would be overturned.

Roe was struck down, which has me hoping that the world can soon witness the return of the pro-life liberal. The left can stop pouring so much energy into a cause that has dubious constitutional merit. The right can turn their attention towards supporting single mothers and perhaps doing what I for years have been waiting for them to do: step outside the lucrative but limited culture war battles, and engage with and support the arts. Maybe we could create more art.

We won the Cold War and overturned Roe. Watching Ben Shapiro annihilate college students is fun, but it’s now time to do something different. The response to cancel culture is not just counterpunching, but creating the kind of questing, beautiful, and provocative art that Hollywood is too scared to attempt anymore. We’ve won the arguments. Now it’s time for the hard part – creating culture.

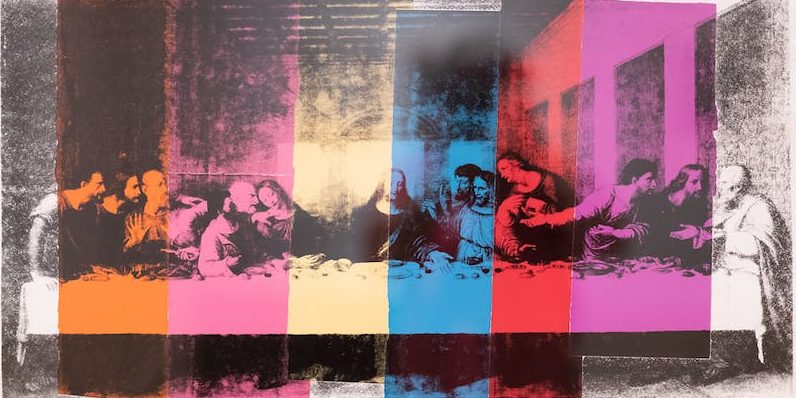

It might seem like I am conflating two very different things, abortion and the arts, but in my personal history, the two have always been linked. The things that I found most crucial in life, that is to say the dynamic and holy experiences of love, learning, and transformation through engagement with the arts, were largely provinces of the left. This was because for decades, liberals built up an impressive infrastructure to support actors, directors, writers, and musicians. The 1980s, my years in high school and college, were fecund, exciting years for movies, literature, and painting in the West. My friends and I would meet in bars and salons and talk about new music, novels, and what Andy Warhol was up to.

At many of these gatherings, politics would come up, with someone inevitably denouncing that dunce Reagan to a chorus of cheers. Eventually, we would talk about abortion. To my shame I would sometimes go along with them, just wanting to avoid ostracism or outright violence. I kept my true feelings to myself. On the rare occasion that I expressed doubt about abortion, the reaction was swift and definite. You were out of the club.

In Chambers’ journey from atheism to a kind of Quaker Christianity, a pivotal moment was the day he examined the ear of his infant daughter, and realized that something so exquisite had to have a creator. This was the same daughter that his communist allies had told Chambers to abort.

Considering what a lifeline books and rock and roll were to me then, it would have been a death sentence. Our celebrities and rock stars demanded to sign off on the dogma. Eddie Vedder of the rock group Pearl Jam scrawling PRO-CHOICE on his arm during a live concert was a kind of dark sacrament that you could not refuse. If you did, you didn’t have the right to listen to their music. You really did become an outsider.

Rereading the articles I wrote for The Progressive, it’s clear that my thinking about art has not changed. Liberalism has. Sure, I’m no longer a socialist like I was when I interviewed Billy Bragg. Yet my review of H.L. Mencken’s memoir The Editor, the Bluenose, and the Prostitute: H.L. Mencken’s History of the “Hatrack” Censorship Case quotes the sage of Baltimore expressing something I stand behind today: “Every censorship, however good its intent, degenerates inevitably into the sort of tyranny that the Watch and Ward Society exercised in Boston.”

Another book I reviewed, Seeing Through Movies, praised the book for its criticism of the corporate takeover of Hollywood and how studios churn out garbage to make a political point rather than art. I have these same sentiments today, just from a different angle. The censorship that degenerates into tyranny is the cancel culture of the left. And the corporate junk that Hollywood unloads on the masses is either woke nonsense, or else the kind of superhero dreck that is obsessed over and celebrated by conservative journalists, many of whom have their jobs not through hard work and acquired knowledge, but via the conservative buddy system and flat-out nepotism. Most of the superhero movies are terrible. The gung-ho Maverick that the right loves is a decent popcorn movie, but not a great film (its prequel, Top Gun, is junk). Conservatives might point to Ben Shapiro, whose Daily Wire is now producing films. The three they have released are Run Hide Fight, Shut In, and Terror on the Prairie. All three are damsel-in-distress dramas wherein a single woman fights off outside marauders. All three are basically the same movie.

Several years ago, some conservative friends and I took on a massive project. We attempted to make a film about Whittaker Chambers, arguably the greatest American anti-communist of the 20th century and the author of Witness, a Bible of the American right. In Chambers’ journey from atheism to a kind of Quaker Christianity, a pivotal moment was the day he examined the ear of his infant daughter, and realized that something so exquisite had to have a creator. This was the same daughter that his communist allies had told Chambers to abort. One can only imagine what a director like Martin Scorsese could do with such a scene. The ear was a central part of the script we spent a couple of years working on as we tried to raise money from donors.

In the end, we did not succeed. When conservatives fail to mobilize behind a movie about Whittaker Chambers, this is like liberals not supporting a film about Martin Luther King. The right doesn’t seem to understand that one film with themes about honor, courage and dying tyranny—say, Zack Snyder’s 300, about the Spartans at Thermopylae—has a greater impact than a thousand think tank position papers.

After our project failed, something interesting happened. I was making some money on the side doing headshots and reels for actors and singers, one of whom made it to the top ten on the show American Idol. The black and white reel I did for her was seen by the actor Alec Baldwin, one of the most popular celebrities in the country—and a man known for his outspoken liberalism. Baldwin expressed admiration for my work, and we exchanged ideas about possibly doing a short video together. It didn’t happen, due to scheduling conflicts and my getting swept up in that D.C. political scandal.

The difference between the experience trying to bring Chambers to the screen and my interaction with Baldwin is telling. Conservatives had a group of people ready to tell the story of one of their great heroes, and we were having trouble getting meetings with people and raising money. It was easier to connect with Alec Baldwin, a famous actor who, like me, had grown up in an Irish-Catholic house that idolized John F. Kennedy. His family had been working class, and Baldwin had risked everything to go into acting. I couldn’t help but share some of Baldwin’s distaste for the right, at least of conservatism’s lack of appreciation for art.

In the fall of 2018, when The Progressive article came out that traced my journey from left to right, I got a call from an experienced Hollywood actor and producer. This person had been in several movies, including one with Johnny Depp. He was marveling that no one had expressed interest in making a movie about what had happened to me. I was a man in the middle: the left hated me because I had defied them during the scandal, not to mention being pro-life. I was a “flawed character” – a former drinker with a bit of a wild past – ensuring that Ben Shapiro would not be interested. The caller then put his finger on it: “This entire thing is a psychological thriller that involves a flawed protagonist. You’d have to go back to the 1970s, to All the President’s Men and The Parallax View, to make it.” I thought of my dad, how much he loved All the President’s Men, a masterful film that still stands up. I found myself thinking back to the night my father took me to see it in 1976 when I was twelve.

We ended our conversation with a promise to talk again. We agreed at least on one thing. One day there may indeed be a film made about my small role in overturning Roe, but such a subtle project would most likely be beyond the ability of conservatives.