A Mixed Account of Modernity

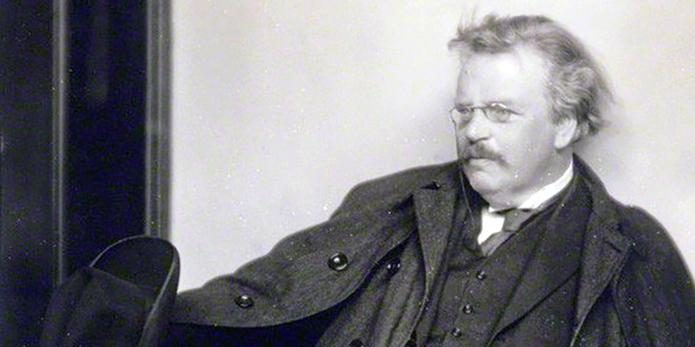

Along with C.S. Lewis and Fulton Sheen, G.K. Chesterton is routinely cited as one of the greatest apologists for Christianity in the modern era and one of the greatest writers and intellectuals of the 20th century. Ironically, Chesterton wrote his most popular and enduring books and essays well before he converted relatively late in life in 1922. Consequently, his arguments for Christianity and against Modernism were always original, imaginative, objective, and fresh.

However, there’s a reason some of Chesterton’s writings are classics and some are not. In matters of faith and morals, his style and approach were perfect; hence these are the writings he is primarily known and celebrated for: Orthodoxy, Heretics, Everlasting Man, and his biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas. Where Chesterton tends to falter is when he broaches the more worldly arenas of politics and economics. These are topics that require a practical mindset and a deep knowledge of specifics, two qualities that Chesterton proudly lacks.

For this reason, reading What’s Wrong With the World, which Sophia Press has recently reprinted, is something of a mixed bag for the Chesterton fan. There are sections where Chesterton really does seem like a “prophet” as Sohrab Ahmari notes in the forward, but there are other sections where Chesterton’s absentmindedness gets the best of him. One can empathize with Chesterton as he tries to contend with the overwhelming forces of industrial capitalism and political progressivism, and point out their corrosive effect on humanity. But so much of that empathy dissolves when it becomes clear that Chesterton hasn’t a clue of what he’s talking about.

Like most conservative intellectuals, Chesterton excels in his ability to identify the logical inconsistencies of the other side, which he brings up in the first section of What’s Wrong with the World, “The Homelessness of Man.” During this time, so many intellectuals and public leaders seemed to lack the capacity to seriously question the corrupt system that had taken hold in England along with the rest of the Western world: a small group of dimwitted rich men reigning over a vast exploited proletariat.

Indeed, more than anything else, this unjust, dehumanizing system is “what is wrong with the world.” But, rather than simply say this, most of Chesterton’s contemporaries searched for ways to either adjust the system or adjust human being themselves to better align with this system. Of the former group, Chesterton responds that such “practical men” are utterly inadequate to the task of reform: “When things will not work, you must have a thinker, the man who has some doctrine about why [various systems and processes] work at all.” To the latter group, Chesterton frankly dismisses them as dangerous utopians, “when one begins to think of man as a shifting and alterable thing, it is always easy for the strong and crafty to twist him into new shapes for all kinds of unnatural purposes.”

Loosely embodying both these fallacious viewpoints are Chesterton’s hypothetical socialist and Tory, Hudge and Gudge. Confronted with rampant squalor and economic inequality brought on by industrialization, Hudge the Socialist wants to evict the poor from their homes in the country and stick them in “a row of tall tenements like beehives.” By contrast, Gudge the Tory wants to keep the poor where they are, “persuading himself that slums and stinks are really very nice things.” Consequently, nothing is done about the poor, the elites continue to exploit them, and the ostensible differences between Hudge and Gudge end up dissolving—towards the end of his book, Chesterton reveals his “suspicion that Hudge and Gudge are secretly in partnership.”

It’s not a stretch of the imagination to note the parallels between Chesterton’s situation and the situation today. While new technologies and various social reforms have alleviated problems of severe poverty and obvious exploitation, there are many 21st-century Hudges and Gudges who collude together to empower the established elite and ruin the working class. The language has changed only slightly: today’s leftist Hudges prattle endlessly about saving the environment and promoting equity while today’s conservative Gudges ramble incoherently about patriotism and free markets, and what results is a lopsided system that leaves people poorer and ever more dependent on Big Government and Big Business.

So what does Chesterton propose to do about this? After all, he’s the one who begins his book with the declaration, “What is wrong is that we do not ask what is right.” If capitalism, socialism, feminism, and progressivism are all wrong, as Chesterton argues that they are, what exactly should replace them?

Humanity doesn’t need new solutions; it needs a new spirit that puts those solutions into practice and finally transforms what’s wrong in the world into what’s right about it.

It’s at this juncture that Chesterton’s argument tends to break down. Concerning the abuses of a capitalist system, in which the rich buy up capital and exploit the working class, and a socialist system, in which the state seizes the land and also exploits the working class, Chesterton briefly suggests at the very end of his book a system in which the government would buy up property and redistribute it to families for private ownership; “if we are to save property, we must distribute property, almost as sternly and sweepingly as did the French Revolution.”

It’s a nice thought, but Chesterton doesn’t seem to accept that workers in an industrialized society lack the skills and attitudes of their landowning peasant predecessors. A government or NGO could take laborers and their families out of their tenement in the city and give them a plot of land in the countryside, but this doesn’t necessarily result in a virtuous family-centered life in which a father becomes a self-sufficient farmer or artisan. What generally happens is that the father will soon want to return to the city where he and his wife could find work and enjoy urban amenities. This was why the Catholic Land Movement that attempted to do what Chesterton proposes never worked out.

Concerning feminism and women’s suffrage, Chesterton is even more vague and often patronizing. In the section, “Feminism, or the Mistake about Woman,” essentially argues that a woman’s anti-democratic, universalist nature is incompatible with a modern democracy and that her purity and inherent domesticity put her at odds with the dirtiness and brutality of politics. While provocative and certainly unique, such claims are unpersuasive and even become morbid at times, as Chesterton asserts, “Here, however, I suggest a plea for a brutal publicity only in order to emphasize the fact that it is this brutal publicity and nothing else from which women have been excluded.” Again, ignorant of the specifics, Chesterton ends up mischaracterizing the mechanics of electoral politics and the demands of the Suffragettes, obscuring the few valid points he makes about femininity.

Finally, concerning progressivism, specifically progressive education, Chesterton seems to struggle with what he wants to say. As a result, the chapters in this section, “Education, or the Mistake About the Child,” come off as loosely connected reflections on the nature and meaning of education, leaving the reader to scramble for the line of reasoning. During this time, much like today, many social reformers saw public schooling as the key to materially improving society and mitigating social inequality.

What one can glean from this section is Chesterton differentiating between schooling (formal instruction in a classroom) and education (the knowledge that comes from experience and personal inquiry), defining the purpose of education, stressing the need for authority in the classroom (more direct instruction, less student-led learning), and calling for a clear ideal for public education. Rather than viewing education through a practical lens that focuses on methods, he sees it through an idealistic lens that focuses on goals. Taken altogether, Chesterton seems to be arguing that public schools shouldn’t conform to the demands of a technocratic state, but should follow tradition and empower individuals.

These are all good thoughts, but the lack of development prevents them from becoming anything more than good thoughts. Moreover, those good thoughts are also accompanied by unpleasant rants about hygiene, sports, and honesty. If one were to give Chesterton the benefit of the doubt, the best that could be said about his points on education is that he thinks that schools are more a tool for the elite to enforce their will on the people than a way to empower the people and inculcate virtue. A fair point, but it needs a clearer defense.

Coincidentally, he does have a chapter in this section about education that resonates perfectly with today’s parents, even saying, “The only persons who seem to have nothing to do with the education of the children are the parents.” But after expressing this bit of truth, he descends back into rants about class and the plutocracy’s detestation of the poor.

All this is problematic, to say the least. For so many of Chesterton’s claims, the reader can simply shrug and respond, “Maybe. Maybe not.” While common sense is a powerful tool, especially in the hands of a master like Chesterton, these issues require more hard evidence. Otherwise, so much of it seems speculative and subjective, the witty lucubration of an obnoxious armchair intellectual.

And yet, even with these major weaknesses in What’s Wrong with the World, it must be recognized that the book is quite good and profound in many places. Even at his worst, Chesterton soars far above so many other writers at their very best. He still has the uncanny ability to get to the heart of a problem, uncover its underlying logic, and touch on a wider truth about human nature. He is still a master of paradoxes, flipping conventional wisdom on its head, and confounding the experts. Most importantly, he still has a sense of levity and color that animates and brings interest to conversations that become overly serious and oppressively heavy.

For that reason, it is still very much worth a person’s time to read and appreciate What’s Wrong with the World. Although Chesterton falls short on solutions, he illustrates the problems quite well, and many of those problems persist more than a century later all over the developed world: a plutocratic elite is still making war on the working classes; the false promises of socialism and progressivism are still featured in public discourse; and the civilizational building blocks of family and tradition are still under attack.

And as Chesterton himself notes, so long as there’s hope, solutions to these societal problems are possible and readily practicable. As he famously puts it, “the great ideals of the past failed not by being outlived (which must mean over lived), but by not being lived enough.” Humanity doesn’t need new solutions; it needs a new spirit that puts those solutions into practice and finally transforms what’s wrong in the world into what’s right about it.