Looking beyond electoral advantage and narrow policy questions suggests that people make progress when they face the future while looking to the past.

Catholic, Protestant, Partisan

“Religion,” wrote Tocqueville, “which among the Americans never directly takes part in the government of society, must be considered as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not give them the taste for liberty, it singularly facilitates their use of it.” James M. Patterson aims in his book, Religion in the Public Square: Sheen, King, Falwell, to explore whether Tocqueville’s observation held true in the 20th century and still offers guidance in the 21st. His method is to look at three cases of widely renowned Christian ministers who spoke and acted in ways that had significant political effect, who were theologically informed but who became known not as theologians but as Christian preachers and leaders. Tocqueville had argued that religion retains its importance in America precisely because it is separate from the state; staying aloof from partisan politics, religion successfully addresses the needs of the human soul while avoiding the vicissitudes of political life, its short-lived successes and inevitable set-backs.

Patterson’s thesis is that Sheen and King succeeded because they carefully eschewed partisan politics, whereas Falwell failed because he embraced it. On the basis of the evidence presented, I thought the thesis was hardly proven, but the author collects enough interesting material and provokes important enough questions to make the book worth reading.

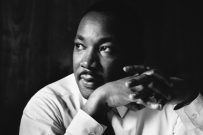

Patterson’s choice to focus on Fulton Sheen, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Jerry Falwell is, so to speak, inspired. Each man was prominent for about a decade-and-a-half—Sheen in the late 1940s and 50s, King from the mid-50s until his assassination in 1968, Falwell from the late 1970s through the 1980s—and each was associated with a political cause that helped define his moment—Sheen with anti-communism, King with racial justice, and Falwell with moral restoration. All three achieved their prominence partly because they were adept in modern media, especially television, with Sheen and Falwell having their own shows, while King masterfully captured the attention of national news reports.

All three emerged as spokesmen for populations that had been excluded from the center of American political life. This is most obvious in the case of King, for blacks had been widely disenfranchised in the South and had been forcibly segregated from mainstream economic and social life when he began his work, but Patterson also shows that Sheen, whose ministry was launched in the aftermath of Al Smith’s defeat and extended through the election of John F. Kennedy, fought for full inclusion of Catholics in the American intellectual and political world, while Falwell was instrumental in returning Protestant Fundamentalists, who had retreated from public life in the 1920s, back into the middle of electoral politics in the 1980 election and beyond. While none of the three preached American exceptionalism, each of the three assigned to the American nation a critical role in the global meaning of his specific cause.

In writing of religion as a “political institution,” Tocqueville had in mind its role in limiting the reach of democratic politics and thereby contributing indirectly to political liberty. Religion, specifically Christianity in its several forms, provided Americans with dogmatic answers to questions about human origins and human destiny—the fundamental questions human beings readily enough ask but rarely have the resources to answer without recourse to authority—and thus brought peace of mind; in addition, it offered moral guidance, for Christians of all denominations basically agreed on what constituted a moral way of life. Although enforced by public opinion—Tocqueville hints but does not say outright that this moral consensus was an example of the tyranny of the majority over thought that he vividly explained—religion was hardly omnipotent, for it could not constrain Americans’ love of material improvement, but it was effective in allowing them a wide range for experimentation in politics and enterprise, for it ensured social stability in the midst of enormous change.

While Patterson draws his framework from Tocqueville, the America he depicts has no such settled place for religion. Instead, Christianity plays a dynamic role for all three clergymen—especially for King—in a world where social change is endemic and religion itself is not fixed. No longer the stable place for the human heart that Tocqueville describes, in a world where churches lined the public square, as it were, and provided a place and a day of rest, religion in the 20th century was swept into the maelstrom of democratic society, or rather retained the engagement with politics that the great reform movements of the 19th century, especially abolition and temperance, had begun—movements whose first stirrings Tocqueville saw but whose full force he had not imagined.

Catholic Americanism

Patterson makes passing mention of Prohibition and of the Social Gospel, but his aim is not to give a comprehensive account of religion in American public life, only case studies, so with Fulton Sheen he jumps into the middle of things. Ordained a priest in Peoria, Illinois, in 1919 and sent to Catholic University for a degree in canon law and then to Louvain for a doctorate, Fr. Sheen joined the faculty of Catholic University and taught theology, then philosophy, for twenty-five years. Already in the 1930s he earned a reputation as a powerful and charismatic speaker, appearing frequently on Catholic radio, preaching sermons, leading rallies, and writing books. With his 1948 bestseller, Communism and the Conscience of the West, Sheen came to national attention and to the attention of Pope Pius XII, who consecrated him an auxiliary bishop for New York in 1951 and made him head of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith in the United States. Launched in 1952, his weekly television show on Catholic doctrine, Life Is Worth Living, drew a huge audience during its five-year run, winning him an Emmy and eventually a place on a major network, ABC. Though Sheen returned to television in the 1960s, albeit with less audience success, and lived to see John Paul II become pope, Patterson concentrates on the height of his influence in the immediate post-war world.

Sheen’s presentation of Catholic doctrine was comprehensive, as a perusal of the titles of his dozens of books make plain, and was within the orthodox Thomism of his era, but Patterson emphasizes Sheen’s embrace of what the latter boldly called “Americanism,” boldly because a papal encyclical in the late 19th century has denounced a heresy under that name and because in the middle of that century the term had been used by the “Know-Nothings” to condemn immigrant Catholics. Sheen, quoted by Patterson, reversed the valence on both counts:

Americanism, as understood by our Founding Fathers, is the political expression of the Catholic doctrine concerning man. Firstly, his rights come from God, and therefore cannot be taken away; secondly, the State exists to preserve them…. The recognition of the inalienable rights of the human person is Americanism, or to put it another way, an affirmation of the inherent dignity and worth of man.

By contrast, for communism, as well as for the fascists and the Nazis, “the state is the source of rights; here man is the source of rights.”

Patterson shows that the contemporary call for Christians to exercise a “Benedict option” and withdraw from public life—except when seeking protection from the courts for their isolation—betrays the legacy of religious engagement with the larger culture and its democratic politics.

In short, argues Patterson, Sheen adapted the rhetoric of a foreign spiritual threat, invented by 19th century nativist Protestants to denounce papists, now to denounce European totalitarianism, seen as threatening the Judeo-Christian consensus of 20th century America and the shared commitment to religious liberty—all the while proclaiming the authority of the Catholic Church in teaching coherently the religious doctrine upon which a comprehensive account of human dignity depends. Outside his teaching and public speaking, his political involvement was limited to his personal relations and appearances with social and political leaders of his era, including several prominent figures he converted to the Catholic faith.

Patterson treats Sheen’s theology with a light touch—leaving unexplored, for example, how his thought on the relation between Thomistic natural law, American natural rights, and modern human rights developed. Moreover, he might have explored these ideas with respect to how Sheen’s contemporaries Jacques Maritain and John Courtney Murray understood these concepts. Another unexplored area is how his engagement with modern psychology in his 1949 bestseller Peace of Soul aimed to deflect the politics of self-expression that emerged in the 1960s. Even if Sheen’s gift was principally as a teacher, not an original thinker, his success in that capacity suggests the possibility, unexplored by the author, of successfully speaking to modern men and women without the sort of compromises that characterized so much of the pastoral work of the Church after Vatican II.

The Social Gospel and Fundamentalism

With Martin Luther King, by contrast, in the strongest chapter in the book, Patterson explains how King’s ideal of the “Beloved Community” emerged out of his theological education in Protestant covenant theology, Social Gospel postmillennialism (the view that Christians’ advancing social justice can usher in the promised thousand-year reign of Christ), and personalism, but King was not really defined by any one of these. Instead, King developed his ideal through his practical endeavors in the movement for civil rights, recognizing that to get Americans to live up to the principles of the Declaration required a change of heart brought on by a deeply religious motive, not just a political commitment: by the sacrificial love of Christian agape that took seriously Christ’s command to love one’s enemies and found a way to put that precept into practice in the midst of fear, distrust, resentment, and hatred across the barrier of race. In Patterson’s account, King used Gandhi’s practice of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience as a method, not a motive; the motive must be love, the will to form a true community, through a process that entailed redemptive suffering on both sides, however different the change required of each and however different the courage demanded of the protestor and the privileged. The civil rights movement was a complex endeavor, with remarkable leaders in law, labor, education, and elsewhere, but King’s religious leadership, Patterson argues, made it possible for Americans to transcend themselves.

That Jerry Falwell is not usually accorded the stature of figures like Sheen and King is of course something Patterson acknowledges. He neither had their university education, nor did he convey the gravitas they achieved or win the admiration of cultural leaders. Still, his influence on American politics—or at least the influence of the religious right, whose growth he helped to spur—is critical to the rise of modern American conservatism and is wrongly neglected by scholars who study contemporary politics. Patterson pays Falwell the compliment of seeking to understand and then make understood his theology, explaining his Fundamentalist Baptist commitment to Biblical inerrancy and his firm premillennialism, that is, his sense that human efforts cannot help along Christ’s second coming, which will happen in God’s good time.

Though Falwell occasionally preached in the style of the Puritan jeremiad—that the nation’s sufferings were brought on by its sins—Patterson emphasizes instead Falwell’s “nehemiad,” that is, his recourse to the story of the prophet Nehemiah, who returned the Israelites to Jerusalem and oversaw the rebuilding of the Temple, teaching them to ignore the ridicule of the wealthy and powerful. Falwell’s aim was to return Fundamentalist Christians to the center of political life, in order to secure for themselves the liberty for preaching the Gospel, his first concern. Having built an alternative media empire of sorts for his religious message, Falwell then became the principal religious figure in the more ecumenical Moral Majority organization, which cemented into Republican politics opposition to abortion, homosexual rights, and other behaviors. Curiously, while criticizing Falwell for his partisan attachments, which indeed depart from the tradition of American clergy that Tocqueville depicted, Patterson does not point out that Falwell’s professed aim was to restore the world that Tocqueville praised, where a moral consensus based on the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule gave society a common point of reference. Surely the Catholic Democrat Ted Kennedy’s embrace of abortion rights in 1980 was as significant for partisan polarization on the questions of the “culture wars” as Falwell’s embrace of conservative Republicans.

I wrote above that Patterson’s conclusion that Falwell failed because he allied his followers with a political party while Sheen and King succeeded because they didn’t is unwarranted by the evidence he presents. This is partly because he stops the story too soon and then jumps to the present. Is it really so clear that Christian efforts to rebuild traditional morality fail before, say, the incorporation of gay rights into the Constitution by Republican-appointed judges in the 21st century? How could Christians accept the sexual revolution without surrendering the Christian teaching on chastity by which, in a previous sexual revolution, the pagan practices of the ancient world had been overcome? And then, is it so clear that Sheen succeeded, when his own career and the confident authority of the Catholic Church he conveyed were broken by the effects in America of Vatican II? King himself, although he was successful in securing effective federal legislation against segregation and the denial of voting rights, and although his martyrdom earned him iconic status in American memory, seems today a figure from another era precisely as a religious leader, for most of the civil rights preachers who claimed his mantle in the next generation lacked his bearing, and today’s movement for “antiracism” altogether eschews religious grounding.

Whatever his explicit thesis, Patterson shows that the contemporary call for Christians to exercise a “Benedict option” and withdraw from public life—except when seeking protection from the courts for their isolation—betrays the legacy of religious engagement with the larger culture and its democratic politics. In its moments of grace and of tragedy, that engagement remains an inspiring project and a reason for hope.