Lloyd was a meticulous scholar who loved life, liberty, and America.

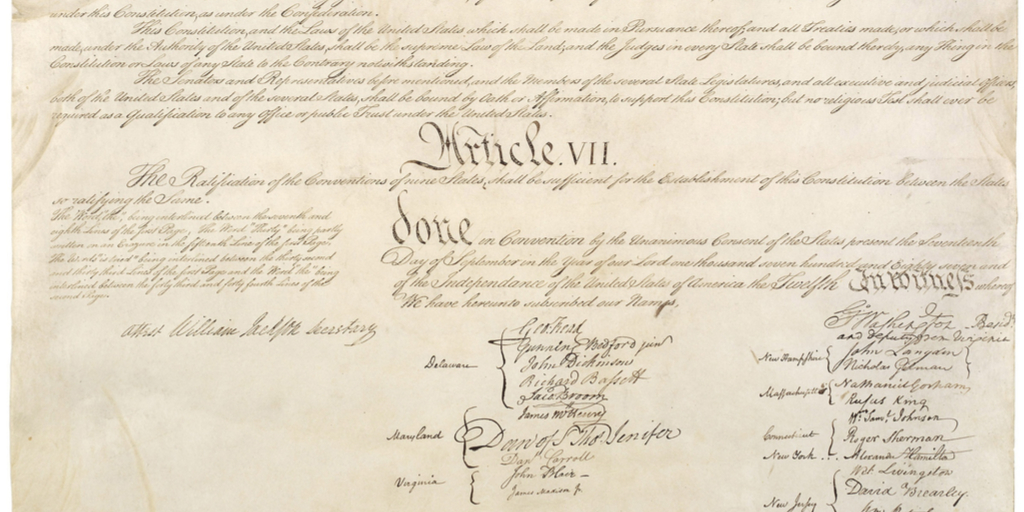

America’s Founders Acquitted

Over the past century, it has been common for academics to describe America’s founders as elitist, sexist, and racist males who created a constitutional order dedicated to preserving their privilege and status. Many of these critics have been and are progressive men and women, with a dominant secularist mentality.

Recently, these critics have been joined by pious conservatives who are concerned with the rampant individualism, relativism, and irreligion that they believe characterizes modern America. These critics lay the blame for this moral malaise at the feet of modernity, in general, and America’s founders, specifically. Of particular concern to Robert Reilly are conservative Catholic critics of the founding, especially Patrick Deneen and Michael Hanby. In America on Trial, he mounts a spirited defense of America’s founders and of the ideas, he says, that made the American founding possible.

One possible defense is to acknowledge and celebrate the influence of modernity on America’s founders. This is definitely not Reilly’s approach. In his mind, William of Ockham, Niccoló Machiavelli, Martin Luther, and Thomas Hobbes paved the way for modern authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. But he defends the contributions John Locke made to the American founding. Locke is often viewed as a quintessentially modern thinker, but Reilly contends that he really stands in the centuries old natural law tradition, which he learned from one of its masters, Sir Richard Hooker. Locke’s focus on the rule of law, property rights, equality of persons, consent of the governed, and freedom under law aren’t modern notions, but they stem back to the medieval tradition of law.

Reilly contends that America’s founders drew from ancient and Christian ideas, including:

the immutability of human nature; the constancy of the universe, the basic goodness of creation; the existence of a benevolent God; the indispensability of Christian morals and the eternal destiny of man in the transcendent, along with their limitations on the role of politics in man’s life.

The founders’ great accomplishment was to put into practice the great constitutional principles of medieval Christendom. These ideas were transmitted to the founders indirectly through Robert Bellarmine, Francisco Suarez, and Richard Hooker. The latter is especially important as he repaired the “damage of the Reformation” and restored “the integrity of reason through the recovery of the classical and Christian natural law traditions.” Hooker, in turn, influenced Algernon Sidney and John Locke, and these two authors had, in Reilly’s account, a tremendous impact on America’s founders.

In making this argument, Reilly wades into the contentious debate over whether Locke is a “thinly disguised version of Thomas Hobbes.” He admits that there are ambiguities in Locke’s thought, but concludes that his political ideas are fundamentally “in concert with the classical and Christian lineage that had proceeded him.” And this is certainly how the founders read him.

No reasonable jury would find America’s founders guilty of the charges brought against them by conservative Catholic thinkers such as Patrick Deneen and Michael Hanby.

There is much to admire in America on Trial, but it contains a flaw which, if repaired, significantly strengthens Reilly’s argument. He is convinced that Martin Luther and the English Puritans were political absolutists who rejected medieval limitations on the power of rulers. Moreover, they “abandoned the ideas of popular sovereignty, social contract, and the requirement of consent.” Reilly agrees with G.R. Elton that, in general, “all the leading reformers preached non-resistance because kings were kings by right divine.”

In describing the “damage of the Reformation,” Reilly focuses almost entirely on Martin Luther. He offers a less-than-nuanced account of Luther’s theological and political views, but the often bombastic Luther gives Reilly material with which to work. With respect to politics, Reilly desires to draw a direct line from Luther to absolutism, but he concedes that Luther clearly stated that there are times when secular authorities should not be obeyed and, after 1530, seems to have moved towards supporting active resistance to tyrants.

Scholars regularly distinguish between Lutheranism and Calvinism, which is important in in the American context because only 1.5% of founding era Americans were Lutheran. On the other hand, between 50-75% of Americans are reasonably described as Calvinists. With the exception of a few references to the English Puritans and one substantive footnote, Reilly ignores these Calvinists. This is problematic because even if Luther rejected the natural law tradition, Calvinists did not—a reality Reilly acknowledges in his exceedingly brief treatment of them.

The vast majority of Calvinist political thinkers advocated limited government and the right to resist tyrants. John Calvin (1509-1564) was among the most politically conservative of the Reformers, but even he contended that inferior magistrates may justly resist a tyrant. However, contemporary and later Calvinists including John Knox (1505–72), George Buchanan (1506–82), Samuel Rutherford (1600–1661), Theodore Beza (1519–1605), David Pareus (1548–1622), Christopher Goodman (1520–1603), and John Ponet (1516–1556) argued that inferior magistrates must resist unjust rulers and even permitted or required private citizens to do so. Note that all of these men were advocating active resistance to tyrants well before John Locke published his Second Treatise on Government in 1689.

Reilly discusses the political absolutists King James I, Sir Robert Filmer, and Thomas Hobbes; none of whom were Calvinists. Indeed, James I and his son Charles I actively opposed the Puritans and were suspected of being crypto Catholics. The English Puritans led a rebellion against Charles I and eventually beheaded him. Such acts are hard to square with the idea that the Reformed Christians embraced the divine right of kings and passive resistance. Perhaps for this reason, Reilly makes only a passing reference to the English Civil War and does not mention the Puritans’ role in it.

More troubling for understanding the American founding, Reilly completely ignores the American Puritans. David D. Hall (no relation), one of the best students of the Puritans, observes that Calvinists in seventeenth-century New England had greater freedom to reform civil government than they did elsewhere. He makes a persuasive case that they created political institutions that were more democratic than any the world had ever seen and that they strictly limited civic leaders by law. One need not join Alexis de Tocqueville in overstating the influence of the Puritans to recognize that their institutions and practices contributed significantly to the American experiment in self-government.

Reilly doesn’t quite say that America had a Catholic founding, but he does assert that the “provenance of the founders’ ideas was ultimately Catholic.” He recognizes that “most” Americans in the era were Protestants, but he never cites the more specific statistic that 98% of them were Protestants. Although he references Donald Lutz’s excellent study documenting the relative influence of European writers on American political thought, he neglects to acknowledge that Bellarmine, Suarez, and Hooker were not cited enough to appear in the study.[1] He does note that Lutz found that the Bible was cited far more often than any other author (indeed, 34% of citations were to the Bible whereas 22% were to all Enlightenment authors combined), which is exactly what one would expect of a Protestant people.

I have focused a good part of my review on Reilly’s problematic account of Reformed political thought not to be critical, but to be helpful. An accurate account of Calvinist thought is actually quite consistent with the “golden strains” of ancient and Christian thought that he rightly believes informed America’s founders. This account ultimately strengthens his argument against those who contend that America’s founders were influenced by ideas fundamentally incompatible with orthodox Christianity. And it helps explain the transmission of these ideas to America’s Protestant and overwhelmingly Calvinist founders.

Reilly is absolutely correct that America’s founders embraced natural law, natural rights, limited government, and the rule of law. They also believed that governments have an important role in promoting human flourishing, although in America’s constitutional order they thought this is primarily the responsibility of state and local governments. No reasonable jury would find America’s founders guilty of the charges brought against them by conservative Catholic thinkers such as Deneen and Hanby. Reilly not only vindicates the founders, he provides arguments that are so strong that a competent grand jury would not even allow the case to go to trial.

[1] Individual authors had to be cited at least 16 times to appear in Lutz’s study. Reilly is able to provide quotations from two founders praising Hooker. He and I are both attracted to one of them, James Wilson, because he offers a sophisticated account of the natural law tradition and its relationship to positive law. For my views on Wilson see The Political and Legal Philosophy of James Wilson, 1742-1798 (Missouri, 1997). Wilson’s collected works may be conveniently accessed Liberty Fund’s Online Library of Liberty.