Architect of the New Deal’s Administrative State?

John Maynard Keynes famously said that “practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” This comment is true of many Supreme Court justices as well. When David Souter was a justice, he channeled the legal process school, dominant at Harvard Law School in his student days, which prized precedent and material outside the statutory text. The justices appointed by Donald Trump reflect the rise of originalism that was ongoing in conservative legal culture when they were young. It might be thought more surprising that the jurisprudence of Felix Frankfurter, a justice who was previously a Harvard Law Professor, mostly reflected a theory that he had imbibed at law school, but that is a persuasive thesis of Brad Snyder in his new biography, Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment.

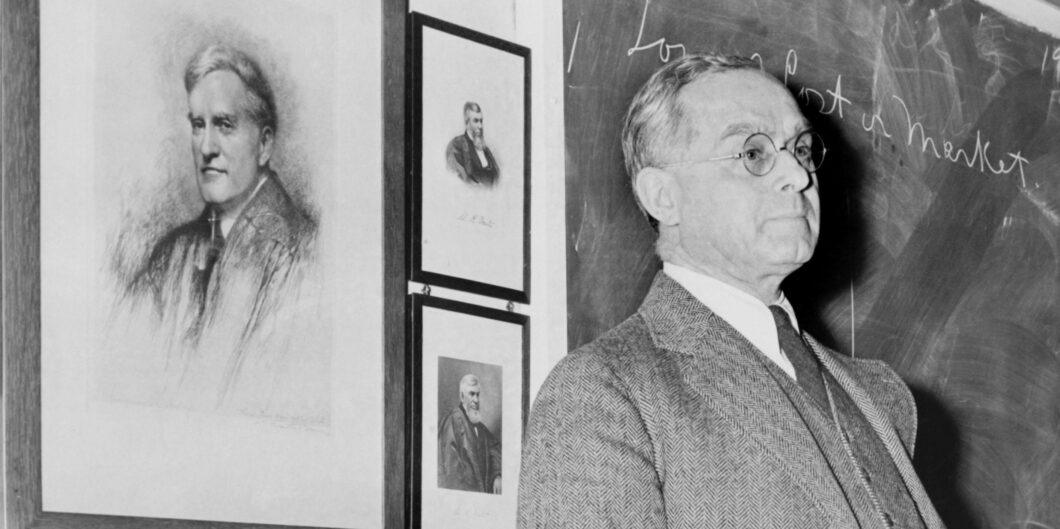

The theorist who is the rosebud of Frankfurter’s career was James Bradley Thayer. Frankfurter himself lamented that he arrived too late at Harvard Law School “to encounter the mind I would have found most congenial.” Professor Thayer had died in 1902 less than two years before. But Frankfurter fully embraced Thayer’s theory of judicial review that deferred to the legislature’s interpretation so long as a “rational person” could embrace it. Thayer argued that “the good which came to the country from the vigorous thinking that had to be done in the political debates . . . far more than outweighed any evil which ever flowed from the refusal of the Court to interfere with the work of the legislature.” Democratic politics was the engine of the good society. The judiciary was, at most, a caboose.

This view informed Frankfurter’s thinking on constitutional interpretation. It explains why, as a professor in the 1920s and ’30s, he relentlessly attacked the pre-New Deal Court that struck down legislation as either beyond Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause or destructive of the property rights protected under the Due Process Clause. In his view, the invalidated reform legislation reflected a deliberative process that was the essence of democracy. Frankfurter’s view of the content of constitutional law was reflected in his arguments to the Court. When he wrote briefs defending the constitutionality of legislation, they were fewer inquiries into constitutional meaning than they were assemblages of facts to show why the legislation at issue was reasonable. His brief on behalf of state minimum wage laws ran 1,138 pages!

Frankfurter’s commitment to judicial restraint also explains why even as a justice in the 1950s and ’60s he did not join other liberal justices in forging a more civil libertarian Constitution by reading the Bill of Rights more expansively than previous Courts and applying it to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment. In Minersville v. Gobitis, Frankfurter even upheld the expulsion of children of the Jehovah’s Witnesses faith from public school for refusing to salute the flag on account of their belief that such salutes were the equivalent of worshipping idols. He emphasized that the way to change the law was through the democratic process, even though the Jehovah’s Witnesses were a small minority. When the Court overruled the decision a few years later, he wrote one of his bitterest dissents, again touting a democratic process that was unlikely to vindicate their interests. His vehement divergence from other liberal justices on the issue of rights was so strong that he compared “the civil libertarian bloc of Warren, Black, Douglas, and Brennan to the conservative Four Horsemen of 1920s and 1930s” who had continually voted to strike down social legislation.

The one exception to Frankfurter’s embrace of judicial restraint was civil rights for African Americans. He supported Brown v. Board of Education. But that case held school segregation unconstitutional despite also declaring that it was unclear whether the Fourteenth Amendment forbade it. Given that (disputable) view of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is hard to square this holding with judicial restraint, despite the strong moral grounds for the decision. But Frankfurter may have again reflected his commitment to restraint when he became a prime mover on the Court in qualifying the force of Brown by suggesting that desegregation had to be accomplished with “all deliberate speed”—rather than immediately as the previous holding of unconstitutionality might have suggested.

The flip side of his judicial restraint was his lifelong activism in the political process. While he became a professor at Harvard Law School, his work there was distinguished not so much by his scholarship but by his ability to identify bright young men to walk the corridors of power. As Snyder nicely puts it: “Decades before the conservatives created the Federalist Society, liberals had Frankfurter.” James Landis and Tommy (“the Cork”) Corcoran, for instance, became legendary New Dealers only because Frankfurter took them under his wing as high-flying Harvard Law students and sent them off to work in government.

Such protégées embodied Frankfurter’s progressive faith that disinterested experts were the solution to the complex modern world. These experts were to be housed in new regulatory bodies and commissions and be regulated by the new field of administrative law. Frankfurter claimed to recognize that “these new premises” would fundamentally transform the law. But he largely focused only on changing the way in which law’s substantive principles would have to accommodate the new facts the administrative agencies would find.

In our renewed debates about how to restrain the administrative state, we are in large measure addressing a problem that Frankfurter helped create.

He gave less thought to the larger structural questions of how the rise of the administrative state might change the deference due to democracy. Thayer’s view was premised on legislators being the prime movers of law, but now experts were the actual rule makers. Why should judges defer to them? The argument in response might be that they were disinterested, but Frankfurter’s own career suggests otherwise. He became an intimate and partisan of FDR, as did all those he sent to Washington. Thayer has criticized the imperial judiciary but what of the imperial administrative state?

Just as Frankfurter was sanguine about giving government over to experts, he also was content to remove the people from the constitution-making process. When New Dealers debated how to deal with the adverse precedent that frustrated FDR’s federal legislative agenda, some argued that constitutional amendments were needed to ratify the comprehensive economic schemes contemplated. But Frankfurter opposed amending the Constitution. Given his view of extreme deference toward the legislature, that position made sense. Almost any federal legislation could be upheld as connected to a very loose and nonoriginalist construction of either the Commerce or Spending Clauses so long as the government amassed enough facts in its support.

But this approach cut the people out of making their fundamental law. So long as the expert-advised legislature acted, the Constitution would follow. While a logical extension of the extreme deference reflected in Thayer’s jurisprudential theories, Frankfurter’s stance ultimately dissolves many constitutional restraints on government. Moreover, since his government is run by experts rather than by the people, it creates a relatively unconstrained technocracy. In our renewed debates about how to restrain the administrative state, we are in large measure addressing a problem that Frankfurter helped create.

Snyder is less searching than some might wish in bringing out the dilemmas that Frankfurter’s jurisprudential and political theory created for him and for the nation. But the biography is no hagiography. He notes that on the Court Frankfurter continued to spend an enormous amount of time advising the executive branch on policy, never giving up his moniker of “Mr. Fix.” During one skit at the national press club, Justice Frankfurter was all too accurately portrayed as getting out of his judicial robes to call the various cabinet secretaries as well as General George C. Marshall. Even beyond his deferential jurisprudence, he was compromised in fairly adjudicating cases that might be thought to affect the war effort, like Korematsu v. United States, which upheld the detention of Japanese American citizens.

He was also not very effective at persuading other justices or the public. In conference, he pontificated like a professor, which irritated his colleagues. His opinions tended to the prolix and disorganized, at least when he did not have a talented editor as a law clerk. As a result, he left more of a mark as an architect of the New Deal than as the author of a lasting jurisprudence.

It is a great strength of Snyder’s book that he shows how Frankfurter was an indefatigable worker and schmoozer as well as a man of genuine warmth with a talent for friendship— all qualities that made Frankfurter a remarkably effective government insider. While he was very smart, having graduated first in his class at Harvard Law School, even smarter people have failed to accomplish much in government through arrogance, diffidence, or inattention. Frankfurter, in contrast, was a consummate manipulator of the levers of power, moving the New Deal forward in all sorts of areas, from utility to securities regulation.

Unfortunately, some of these positive qualities, like that for friendship, deserted him in the small confines of the Supreme Court. His delight in networking led him to maintain improper extrajudicial contacts. And most of all he lacked some of the essential qualities, like dispassion and distilled eloquence, that make for a truly great justice. Frankfurter was the rare lawyer whose career had a more lasting effect on the nation before he joined the Court than when he sat on it.