The German ordo-liberals may offer a path for reforming today's central banks.

Forging an Empire

Germany’s importance to Europe and the world since the 20th century obscures the relatively short time it has been a country. Compare its establishment in 1871 with that of the United States in 1776 or the United Kingdom in 1707. France, Russia, and Spain have undergone transformative political changes, but have much longer histories as recognized states. By contrast, Germany before its unification was a geographic expression comprising a variety of separate realms sharing a common culture and language. That history shaped both its emergence as a country and the empire ruled by the Hohenzollern dynasty until 1918. Despite underlying political and social fragility that cut against its intrinsic strengths, Imperial Germany survived the strains of World War I and subsequent pressures to fragment the country into its original components. What made it fragile and lasting at the same time?

Katja Hoyer, an Anglo-German historian born in East Germany, addresses that question in Blood and Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German Empire. A concise, well-written study, it deftly blends narrative with analysis to set a crucial era in the context from which the German state emerged. Hoyer draws her title from Otto von Bismarck’s famous 1863 September speech declaring that force, not constitutional procedure, would unite Germany. Victory in a series of limited wars provided Bismarck the opportunity to proclaim a German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles on January 18, 1871, but this process made conflict its primary binding force. Rather than a solid edifice, Hoyer describes the federal empire as “a mosaic, hastily glued together with the blood of its enemies.” Bismarck used the struggle against foreign and domestic threats as a unifying force, but successors managed that difficult balancing act far less well. Although their careless steps produced the conflict that brought the monarchy’s downfall, fifty years of economic development and population growth provided Germany the cohesion to last through its transition to a republic.

Bismarck Constructs an Empire

Before unification, German history offered little to assure that cohesion. The medieval German empire had never drawn together into a true realm, especially since ambitious emperors looked over the Alps to bolster their influence in Italy. Furthermore, a confessional divide since the Protestant Reformation reinforced divisions within Germany. Habsburg efforts to enhance imperial power also failed in the Thirty Years War, which ended by recognizing the authority of German princes within their own domains instead of the Holy Roman Emperor. As Voltaire famously quipped, the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, Roman, nor an empire.

The rise of Prussia would later create a formidable threat to the Austrian Habsburgs’ control of the Empire. Whether Prussia or Austria would lead Germany remained an open question until the latter’s defeat in 1866.

The French Revolution followed by Napoleon’s invasions of the German kingdoms served as a catalyst for German nationalism. Indeed, Germans saw the struggle against Napoleon as a war of liberation, but the settlement arranged at the Congress of Vienna disappointed patriotic sentiment. Germany remained divided into separate realms in a confederation dominated by Austria with Prussia a junior partner. While sharing a common mythology and language, the German people primarily were loyal to their home regions. And those who wanted a united Germany, like liberal nationalists, faced conservative distrust of revolution and resistance to any change in the existing arrangements that favored individual principalities. Prussia’s Friedrich Wilhelm IV refused what he called a “crown from the gutter” when the Frankfurt Parliament approached him to rule a united Germany.

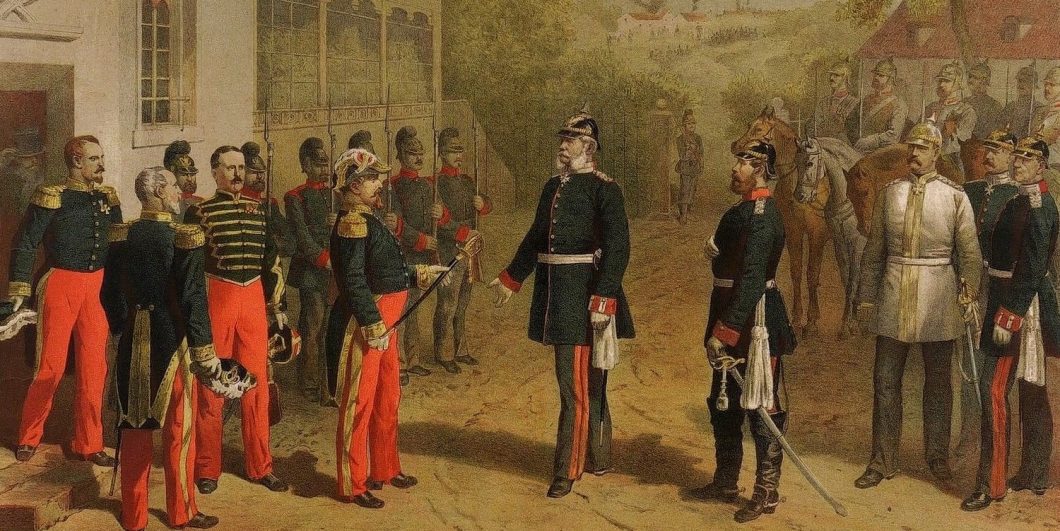

The realization of liberal nationalist aspirations for unity came only through the decidedly illiberal Bismarck who appreciated Germany’s conflicting impulses better than most. He dominated politics not only during the process of unification but also through critical early decades when the empire took form. Military reforms that increased the number of troops and ensured the Prussian army’s loyalty to the crown provided a vital tool for unification—one that Bismarck secured by overriding parliament and breaking constitutional rules that set a lasting precedent. Hoyer emphasizes his view of “liberalism as fanciful intellectual indulgence” and belief that only actions, not words, could get things done. Those actions using conflict in a sequence of calculated risks taken without regard to principle or political morality cut against conservative instincts as well as liberal principles. Nonetheless, even as Bismarck moved decisively to accelerate unification by conducting a series of limited wars, he knew when to hit the brakes and show restraint.

Indeed, Bismarck checked demands to impose harsher terms on France after its defeat just as he supported reconciliation once Austria had been pushed out of German affairs. Unification made Germany a satisfied power with a stake in the new status quo. Bismarck focused now on keeping what he had secured.

A federal constitution with devolved powers recognized the importance of the states, but Prussia dominated, both by its votes and by the fact that its king was Germany’s emperor. Universal manhood suffrages operated alongside mechanisms to preserve aristocratic and business influence. Culture, custom, dialect, and history pulled Germans to regional loyalties even as they shared a country. The system Bismarck established, along with the foreign diplomatic alignments he forged to protect it, required careful balancing. At home, this meant reconciling competing interests and fostering loyalty to the Reich without encroaching too much on principalities that would spark resistance. Abroad it involved marginalizing France diplomatically while making alliances to minimize conflict among other powers that might affect Germany.

New Enemies

Rallying Germans against perceived threats to national unity gave Bismarck a valuable tool. The so-called Kulturkampf against political Catholicism declared those who undermined German unity to be enemies of the state. Liberals committed to secularism backed his program to take education and marriage from church control and push clergy out of politics. Hoyer describes Bismarck’s efforts as a battle over spiritual and moral authority in the new empire. The state would not tolerate rival claims for allegiance. Although specific measures, including civil marriage and educational reforms stuck, they also sparked a backlash. Many conservatives, alarmed by moral and theological relativism, found the program too radical. In response, Bismarck dropped his partnership with liberals for a rapprochement with conservatives and the rising Center Party. Socialism would become the new enemy within.

Hoyer argues persuasively that building a German empire on war ensured its eventual collapse. Maintaining national unity required a steady diet of conflict until the catastrophe of global war brought it to an end in blood and iron.

Economic growth created the conditions that made socialism a force even as it strengthened Germany. Coal, iron, and other resources made lands along the Rhine, which Prussia secured in 1815 as a barrier to France, the richest jewel in Prussia’s crown. They became the foundation of German industrialization that drew on technical skills to develop industries in chemicals, electrical goods, and mechanical engineering along with steel and coal. A customs union had facilitated development even before unification and Bismarck adopted protectionism over liberal resistance to secure a domestic market. Partnership between agrarian and industrial elites—the so-called rye-iron alliance—dominated German politics. Infrastructure development linked resources, manufacturing, food, and population centers with railroads that served industry rather than passengers. Higher agricultural productivity shifted the workforce from agriculture to industry. A stable food supply increased population and the labor supply. These factors created a virtuous cycle of economic growth that shaped Germany with lasting effect.

A financial crisis in 1873 briefly dampened economic confidence, but Hoyer argues that, with a steady rise in living costs, it had lasting social effects by framing liberal capitalism as exploitative. The spike in share prices driven by excessive investment brought Germany’s first recession which hit vulnerable groups hard. Without liquid assets to weather the crisis, many in the middle class lost fortunes made from banking and investments. Landed interests saw the fragility of their wealth, while workers reliant on wage earnings struggled with high costs and poor conditions. The situation provided traction for anti-Semitic critiques of finance despite a pattern of Jewish assimilation, which the government encouraged. Hoyer notes suspicion against progress in the countryside where inhabitants had less access to rail travel. There also was a growing distrust of urban modernity, along with a broader move against liberalism itself. A trend among the nouveau riche of copying aristocratic styles reflected a turn away from the bourgeoise sensibility that fostered it. Social reform became a way to blunt discontent among urban workers even as Bismarck framed labor militancy as a challenge to the nation. Socialism replaced political Catholicism as the anti-national force to guard against.

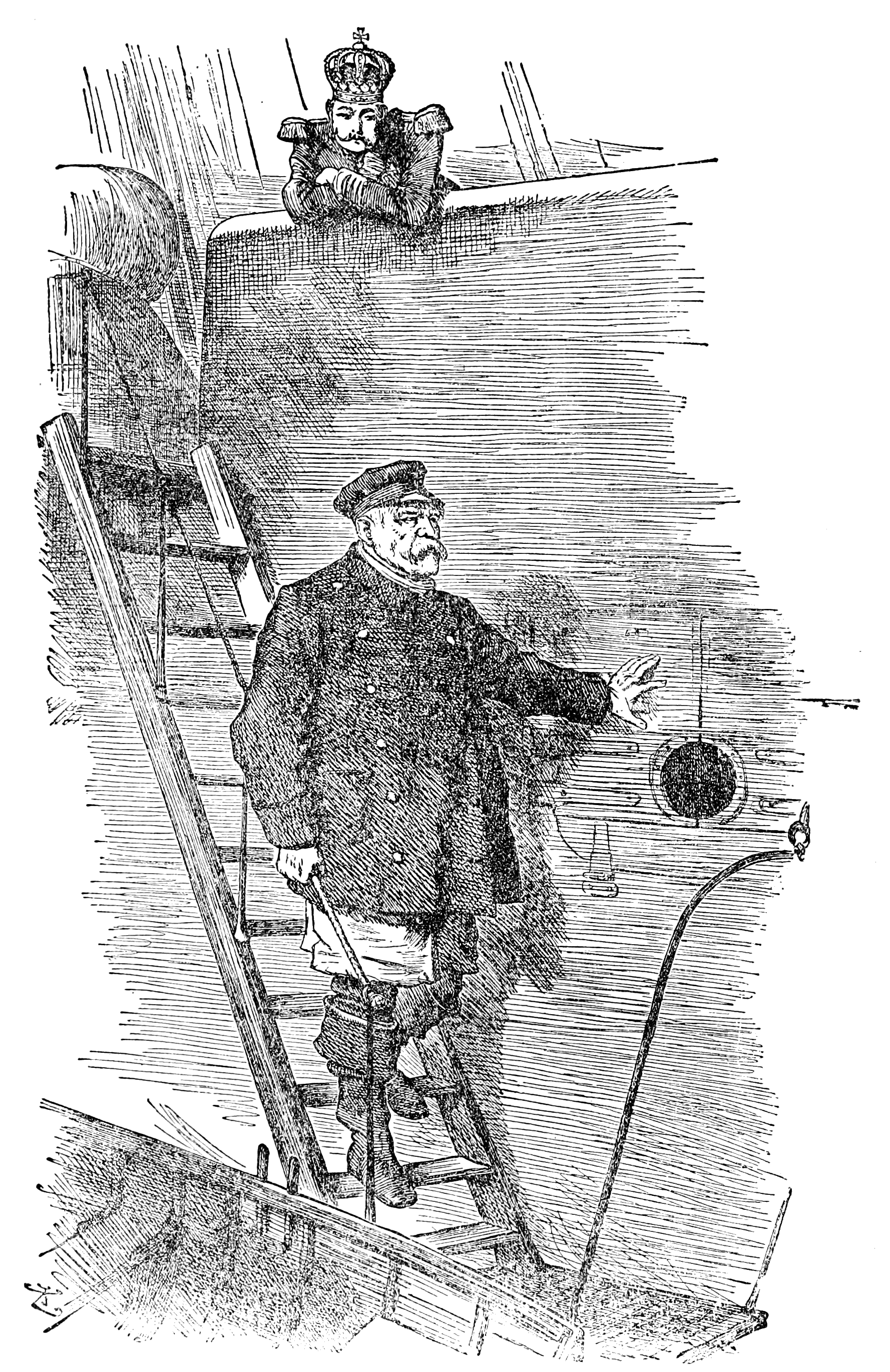

Hoyer describes the stamp Bismarck left on Germany that lasted into the 20th century. Besides reforms like social insurance and state control over marriage and education, the powers he exercised in the chancellorship gave it the authority later used by Konrad Adenauer, Helmut Kohn, and Angela Merkel. Although Bismarck dominated William I as much as the empire, other Hohenzollerns were less pliant. Empress Augusta distrusted him, while the heir, Friedrich, and his wife Victoria had a very different liberal sensibility. The chancellor cultivated their son William, who quarreled with his parents, as a counterweight, but the prince’s accession as emperor after his grandfather and father died posed a new problem. William II declined to follow Bismarck’s lead or approve his crackdown on worker demonstrations. He called the chancellor’s bluff on a threat to resign in a moment captured by a famous political cartoon by Sir John Tenniel entitled “Dropping the Pilot.”

A New Path to Destruction

William II’s determination to chart his own course opened a new chapter, but the emperor could neither fill Bismarck’s place directing government nor find an effective minister who could. Relying on favorites rather than working through constitutional structures brought to power men pursuing their own agendas. A weak emperor guided by passing enthusiasms left a dangerous power vacuum at the heart of government. Leo von Caprivi’s early attempt at pragmatism in the 1890s failed to lessen tensions within society and his successors as chancellor fared little better.

Hoyer rightly describes William II as a man of his time and place with a passion for modernization the public largely embraced. Technological change and urbanization reflected in Berlin’s growth set the tone before 1914. As industrial production outpaced home demand, the economy shifted to exports. William II’s nautical interests and increased consumer access to goods from beyond Europe, along with a new mass popular culture, fueled an enthusiasm for colonies that Bismarck had resisted. Germany’s global ambitions marked it as a rising, unsatisfied power. Bismarck’s delicate balancing that excluded France, kept good terms with Britain, and made Berlin the center of European alignments gave way to the nightmare of an encircling coalition that he had feared. Rapprochement between France and Russia followed by a shift of alliances among Europe’s leading states set the conditions for general war.

National unity required at least the illusion of a defensive war as the July 1914 crisis broke out. Social Darwinist thinking that had become so prevalent in Germany made the conflict nothing short of a struggle for survival. The Burgfrieden or fortress truce of national unity suspended regular politics and the Reichstag gave up its powers voluntarily. Press censorship and the sidelining of debate gave the public a distorted picture of events on the front that amplified the later shock of setbacks and eventual defeat. The army’s seizure of executive powers not only suspended democracy, but also curtailed William II’s effective authority, making him a figurehead for the generals, especially once Paul von Hindenburg and Erich von Ludendorff took control.

Massive casualties made both sides reluctant to compromise. Anything short of victory threatened domestic backlash. Steep war aims emerged to justify losses. Dependence on imported food and earnings from exported goods heightened strain on the German home front. Hunger, especially during the “turnip winter” of 1916, and fuel shortages made civilian life increasingly hard. War finance relied on making defeated foes pay the cost. Blockade closed exports and the earnings they brought and Germany could not borrow to sustain its efforts as Britain and France did. Its leaders fatally bet instead on exacting reparations from defeated foes as in 1871, and the inflationary combination of debt and paper currency not backed by gold meant that a peace without gain would ruin Germany economically. Even as it inflicted social trauma that scarred the nation, leaders determined to push the war to a final decision that bought the monarchy’s downfall in 1918.

Hoyer argues persuasively that building a German empire on war ensured its eventual collapse. Maintaining national unity required a steady diet of conflict until the catastrophe of global war brought it to an end in blood and iron. Fragile institutions made Germany dependent on one man—Bismarck—without the resilience to remain stable without him. Yet Germany survived even as the Kaiserreich fell victim to its own hubris. Ironically, war bound Germans together in shared misery. Even before the catastrophe of 1914, several generations had grown up knowing little else. The society and culture forged after 1871 had been their normality and there was no going back to an earlier world with its different loyalties. Forty-eight years together, Hoyer concludes, made disunion unthinkable.

Closing Blood and Iron with the Kaiserreich’s downfall in 1919 leaves open the question of what that period meant for Germany’s later history. Hoyer remarks that Britain and the United States saw the potential in the legacy of unification for a national vision resting on trade, stability, and rule of law, but also points out that alternative only emerged following another more catastrophic war. While democracy in the interwar years lies outside her story, she implies it became a lost opportunity realized only after the Nazi period. Democratic Germany shaped by Adenauer and Ludwig Erhard had roots in the Rhineland and emerged under Anglo-American protection. Reunification came through talks and money rather than blood and iron. National identity has taken a back seat to European unification and other ideas, but the question of Germany’s place among leading powers and relationship with its neighbors remains open.