Somewhere between Horror and Hope

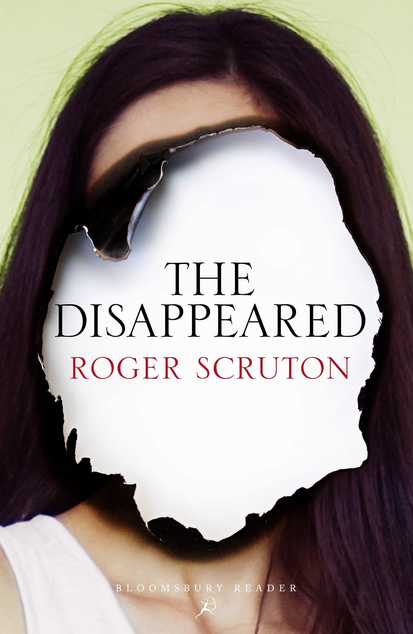

Writing a novel that resonates with current headlines may draw attention, but it’s a mixed blessing—there’s more than a chance that confusion with the contemporary will obscure more enduring issues. The departure point for British philosopher Roger Scruton’s fine new novel The Disappeared is as dramatic as it could be, but its implications are so serious, and Scruton’s understanding so nuanced and complex, that it becomes something rich and strange.

No one can have missed the horror story uncovered in the Yorkshire town of Rotherham, far too slowly, over the last decade and a half. According to a “conservative estimate” arrived at by the independent inquiry eventually commissioned, there were in that period more than 1,400 victims of systematic child sexual exploitation. The victims were almost all white girls, children and adolescents from the margins of the underclass. Children “in care,” children whose households were disrupted by the absence of adult authority, or order, or just of supper, were “groomed” by adult males who sexually abused them or pimped them out across the north of England. Uncomfortably for the authorities, almost all the perpetrators were South Asian men from Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Afghan backgrounds.

Despite task forces and committees, and the sustained involvement of some social service workers, efforts to stop this exploitation were grossly inadequate, not least because of institutional fears of appearing racist. So the girl who was doused in petrol and warned at the end of a lighter not to report her rape, the drunk and drugged children arrested while their groomers were left free, were undefended by the law.

The Disappeared resonates, intentionally, with the Rotherham disgrace. But Scruton has imagined its story in another context as well, offering possibilities of transformation and hope without trivializing tragedy. By echoing The Tempest, possibly the greatest humanist story, he invites consideration of these possibilities; that it is the great English story suggests how they might be realized.

Set in the declining Yorkshire town of Whinmoore, The Disappeared tells of two youngish Englishmen, several younger women, and their tragic encounter with forces unleashed by collision at the sharp edges of culture.

Stephen Haycraft has wandered into a teaching job at St. Catherine’s, a state school serving the neighborhood of Angel Towers, council housing for immigrants and the umpteenth generation of Britons on benefits. Numbed by the indifference of students and teachers alike, Stephen is astounded to receive a series of extraordinary essays from the unlikeliest of sixth-formers. Sharon Williams of the Towers is what the bureaucracy unironically calls a “looked after” child, that is, in foster care, and as Stephen begins to recognize, dreadfully abused.

Through her essay on The Tempest, thrust shyly at Stephen, Sharon demonstrates a remarkable understanding of Shakespeare’s last play. Her intellectual sharpness is complemented by an inferential sensibility, which allows her to recognize herself in Miranda. Sharon, though, is unprotected from the local Calibans who rape and abduct young women, beat them, and sell them to mysterious buyers in Russia. Appalled, Stephen contacts social services, but social worker Iona Ferguson can’t imagine that an essay on fiction could itself be anything other than fiction. Meanwhile Iona puts credence in other reports of wrongdoing, such as that concerning a girl in care “whose adopted parents were real racists.” They “took against the Afghans and Iraqis in a big way,” spreading “stories of rape” that made the girl run away. Stephen, however, knows that she did not—she was abducted and sold in Russia.

At about the same time, an environmental planner, Justin Fellowes, is rattled out of his routine by seeing Afghan men attempting to force the return of a young woman to her family in the Towers. Along with others, Justin offers to walk the young woman, Muhibbah Shahin, to her flat. He is instantly fascinated by her beauty and self-possession and helps her find a job in the green energy company where he works. She’s a quick study, rapidly learning to handle complex projects and discussing her reading with him. Though Justin is strongly attracted to her, and she agrees to go to a play—guess which—she makes it clear that she doesn’t reciprocate.

Muhibbah disappears from the office one afternoon, leaving behind only hairpins and a ribbon. Though her roommate tells Julian that she’s packed up and “skedaddled” on her own, he reports her disappearance to the police, reminding them of the previous problems with the Shahin family. And the police assure him of their commitment to “sensitive policing” (that is to say, their determination to do nothing that might be construed as racist). As Superintendent Nicholson reminds him, there had recently been a case in which a headmaster “insisted that Muslim children should obey the same rules as whites,” which resulted in the headmaster’s dismissal. “Naturally we don’t want any of that on our watch.” And he backs rapidly away, assuring Justin that if “sufficient evidence” turns up the police will investigate.

By the time Justin notices Muhibbah’s computer has disappeared, he is worried that reporting it might incriminate her. And when he realizes that she’s fiddled the books, he is sufficiently preoccupied with her wellbeing to forgo reporting that to officialdom, either. He confides his worries to his social worker friend Iona, but guardedly—he is savvy enough about social work “to conclude that the thought police had its headquarters there.”

The parallel crises, of Sharon’s safety and Muhibbah’s, collide dramatically when another young woman is accidentally caught up in them. Laura Markham, hired by Justin to investigate his doctored books, is shanghaied (chloroform and all) in mistake for Sharon, who’s eluded her vengeful abusers from “the Angel.”

So far, so melodramatic. But the overlapping of these crises is less contrived than it sounds. Whinmoore is not a large place, and the anti-community of the Angel Towers is even smaller and less various. Sharon’s stepfather, a Polish ship captain, is the one who has been smuggling women into Petersburg. The kidnappers are Muhibbah’s brothers, bewildered Yunus and vicious, wall-eyed Hassan, part of the trafficking network that is the Shahin family business. The story is so vividly presented that what seems impossibly coincidental in broad outline is suspenseful and quite frightening on the page. And what we know of the Rotherham outrage has made it clear that the unimaginable can be literally true.

The novelist has clearly enjoyed himself in choosing his characters’ names, by the way, and I don’t think he means us to miss their significance. The confused and ineffectual Yunus is called “dove,” but the surname Shahin means “falcon.” It is a gentle irony that the well-intentioned but politically correct Iona bears the name of the island home of early Irish monasticism. “Krupnik” is apparently the name of a Central European rotgut, appropriate for the violent sot Bogdan who is the liaison between the Shahins and a set of shadowy Russian criminals.

The two most significant names, naturally enough, are Muhibbah and Sharon. As Muhibbah tells Justin, her name means love, or loving, or that which is loved or lovable. Whichever of these it means at a given moment, it is clearly intended to remind us again of Miranda, whose name means “admirable.” The less fortunate Sharon bears what is possibly the original “chav” (loutish working-class) name, and indeed it sits like a weight upon her.

Meanwhile, as we say in drama, Laura, abducted and bound for Russia, responds more directly to her circumstances than either Sharon or Muhibbah. Innocent of the snares and undercurrents that terrify them, she literally throws a wrench into the works by bashing her would-be rapist with a spanner and causing the ship to turn back for a doctor. But the botched kidnapping has unleashed disaster. The crime lords in Kaliningrad don’t take kindly to losing either assets or face and nor do the local ones, who seek their own revenge.

Events unspool quickly—dénouement has rarely been as apt a word. Stephen rescues Sharon from a murderous attack and gives her refuge with him, but his failure to inform social services results in arrest and disaster. Justin’s attempt to find and rescue Muhibbah is foredoomed to miscarry. Stephen is convicted of child abduction, accepting both the bitter irony and the justice of imprisonment. Muhibbah falls victim to a far more rigorous code, vengeance rather than justice. Stephen is released from jail, and some, if not enough, of the predators are jessed and hooded. Every character in the novel has been more than ordinarily entangled in circumstance, and extricating themselves requires a great summoning of will and understanding.

If all the action ended here, The Disappeared would be a tragedy instead of a tragic romance. But I suggested that Scruton’s many allusions to The Tempest, the overt and the subtle, are there to imply a different ending. Of course The Disappeared is not a paraphrase of the play. At the same time we’re missing a great deal if we don’t notice their similarities and, possibly more important, their differences.

The most important similarity is they are both romances. Despite the catastrophic events that toss them about, despite encounters with a depravity that would make Caliban blush, Stephen and Sharon, Justin and Laura, not only survive but promise to endure. As Iona recognizes finally, what is necessary is not dealing with the “isms” at the top of her social work agenda; what is necessary is to “give [Sharon] back her life.” Sharon’s indomitability helps heal Laura and others—“she was proof that you could be raped, humiliated, treated as a thing, and still be able to give yourself freely.” What Iona sees is grace accorded the battered protagonists, and the moment in which the formation of private bonds illuminates the way forward.

But if private life is being revived, there remains one very important public obstacle. Where is Whinmoore’s Prospero? The short answer is, there’s not one. A more enlightening answer lies in remembering the magician correctly, for in the transport of that wonderful play it’s all too easy to forget Prospero’s complexities. He abjured his office and his civic responsibilities to make himself a Magus—practicing “white magic,” to be sure. But he’s still off dabbling in gnosticism and meteorology and not where he’s supposed to be.

Can it be that Whinmoore is like abandoned Milan as well as like the island to which he repaired? Without any apparent political regime, the town’s corrupt bureaucracies flourish along with criminal gangs. Civil society descends below the level of common decency. In the absence of a coherent politics it’s no accident that there’s a reversion to the tribal level, literally in the case of the Afghans, or that the desire for vengeance would vie to displace justice.

No simple solution suggests itself, but Scruton gives us clues to think on. The moral wasteland of Angel Towers may be mitigated by the implied marriages of the four young people. If Sharon can understand so much of her own difficult life through reading Shakespeare, perhaps traditional education offers truths to those who can hear. And if Laura, armed only with a wrench and her beloved copy of The Wind in the Willows, has the courage to strike back at her abductor and extricate herself from an untrustworthy ship, there seems room at least to hope that other Calibans, other monsters, may be vanquished through courage and good character.