Caught Between Creed and Covenant

In After Nationalism, Samuel Goldman takes issue with the idea that citizens of the United States can ever really share a distinct and coherent national identity. He argues that theorists and activists alike tend to aspire to a cultural bond and a unity of purpose that the nation we actually live in can’t really give them. A deep sense of national unity, he reminds us at the beginning and end of the book, has been profoundly abnormal for most of American history, and asserts “we tend to forget,” for the brief periods where it was the norm, “just how much coercion was involved.”

After Nationalism traces the symbolic importance of three movements and outlines the matters that their adherents hold most dear. Covenantalism focuses our attention on origins, on the peculiar lineage of America as Anglo-Protestant heirs to God’s covenant with the nation of Israel. Creedalism emphasizes the ways that America itself rests on a distinctive political philosophy that can admit all citizens who accept its guiding truths. Cruciblism leads its adherents to view America as a melting pot, “in which ethnic and cultural particularities are boiled down into a consistent alloy.” Goldman seems to wish that each of these views could be relegated to its proper place—their mythic status dispelled and their partial truths absorbed in a way that moderates citizens’ minds. He certainly argues that all these symbolic views help us see some aspects of our national life clearly. The trouble with the book, however, is that it seems to lean in the direction of the political equivalent of the Hippocratic oath in which the best solution is that which does “least” harm—and does not necessary seek to help us find a workable political cure to the ills it identifies.

A few people really do seem to relish the idea of a coerced revival of their own imaginatively constructed fantasies of unity. Goldman offers a corrective against this notion: not only does “mandatory solidarity… not always succeed,” but proponents of any sort of new nationalism rarely seem to acknowledge the “disproportion between historical means and desired ends.” These facts help explain “the distinctly rhetorical quality of the present nationalist revival.” Advancing a carefully balanced pluralism, Goldman contends that while “covenant, crucible, and creed are all part of America… none exhausts its past or prospects.” One might ask, though, whether such careful balancing acts tend to emerge naturally in—or even appeal to—Americans.

Consider the fate of the (largely moderate) crucible: The “melting pot” theory of American life more-or-less disappeared in the face of multiculturalism in the 90’s. Today, talking about America’s distinct ethnic cultures melding into a higher unity is a sure path to cancellation. Even though Goldman is at pains to show the ways the melting pot tended to marginalize Catholics and members of ethnic groups further outside the WASP-ish East Coast elite, he nonetheless observes that the symbolism of the crucible offered some major advantages to the nation: In addition to an orientation toward the future, “[t]he crucible… is associated with voluntarism and rebirth”—sensibilities that tend to be lacking in today’s partisans of a new American covenant and reinvigorated American creed.

The Covenantal Imagination

Goldman ably traces the various ways that the old sense of national covenant based on a particularly Protestant sensibility fell apart. He also suggests that covenantal conceptions of nationhood persist because

Covenant theology provides a way of avoiding the abstraction of a purely political understanding of the people without moving too far in the direction of blood and soil. By placing the community as a whole in a “vertical” relationship to God, covenant also establishes a “horizontal” responsibility among its members.”

In abandoning “Calvinist obsessions with sin and predestination,” the young nation left behind a concept of the covenant based on purity, but it did not depart from the pattern of theological and covenantal thinking—a pattern across our nation’s history that has tended to persist whether or not its expressions were even overtly theological.

The old covenantalists would remind us of crucial benefits that flow from their beliefs. Deep religious conviction allows the community both a sense of the reality of sin but also a means of understanding forgiveness. The need to live up to the high calling of the covenant can promote not just an ordered kind of liberty, but also a deeper care for one’s neighbors. At the same time, the covenant is not only plagued by continual factionalism over differences in theology and practice, but also frequently succumbs to the temptation to purge those on the fringes of the covenant. Heretics and dissenters must constantly beware, lest an unguarded word reveal their disloyalty.

If my description of where covenantalism tends to lead sounds familiar, it might surprise readers that After Nationalism’s main discussion of covenantal ideas ends with the nineteenth century. Goldman only picks the concept up again in his conclusion, at that point focusing on Samuel Huntington. Yet far from the covenant belonging to the old Moral Majority or the like, it’s the left that predominantly holds this terrain today in a way and they do so with deeply evangelical fervor. That’s not to say that there aren’t serious conservative Christian thinkers who frame their understanding of the nation in deeply covenantal terms—but they are a distinct minority. While he notes a few thinkers who articulate what covenantalism has to offer the modern nation, Goldman misses the central expression of covenantal thinking in our moment—that found in identity politics.

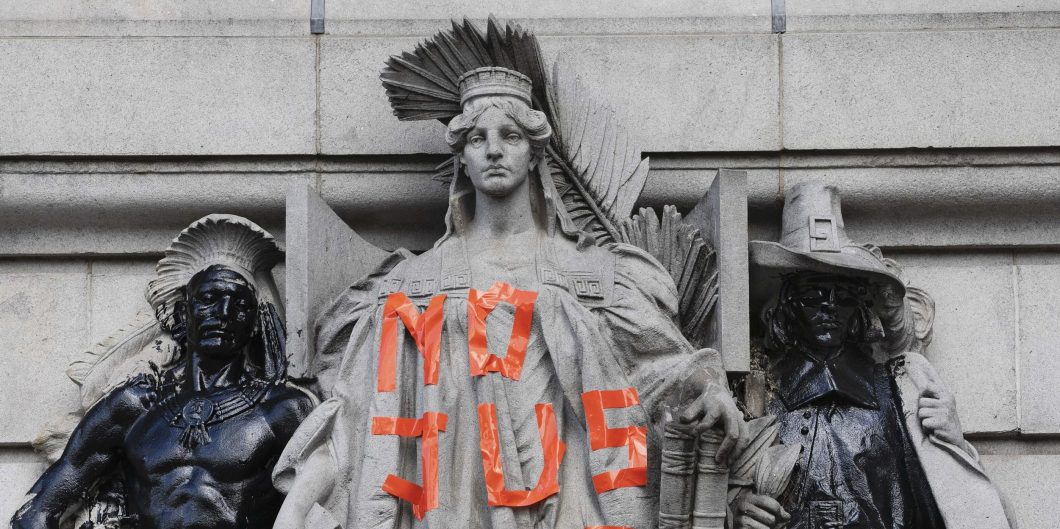

As Joshua Mitchell has most persistently asked, how else can we explain the peculiar tendencies in identity politics? Our woke covenantalists do not just seek some concrete political settlement in favor of equality—they desire a purified nation, a washing away of moral stains only possible by the progressive cancellation and harrying of the guilty (read: the white, privileged, and deplorable) in a worldview that having lost any transcendent faith, denies any basis for forgiveness. This results in a pitiless understanding of the past, but also a certain symmetry in their focus: where orthodox covenantalists used to be “oriented toward patriarchs who established a sacred community,” and prized “deference to great ancestors,” the new identitarians are also peculiarly obsessed with the past. Yet they look to the past in order to expunge the legacy of white sin. The new covenantalists among our journalists and historians work tirelessly to show that our nation’s founding is irretrievably tainted by this new original sin of white oppression.

That this vision offers little more than a pitiless future of disunion does not trouble the woke. In the face of this, it ought not surprise us that many on the right look to a unifying idea of what America is and may yet be in order to move forward.

Creedal Passions

On the right, America’s frustrated creedalists see the progressive constitution as an inversion of all that is good and true in the national story. They look to our nation’s founding as a source of wisdom for—and limitation on—our ambitions in the present day. In Goldman’s telling, the “search for a creedal nation was a failure,” and remains so. Nonetheless, Goldman’s recounting of creedalism’s origins makes for fascinating reading, and it helps clarify why the creedal desire for more—or better—civic education will never quite capture the fugitive unity they believe will help restore our greatness.

Many of the creed’s most prominent early theoreticians were foreigners looking on America’s peculiarities from the outside. Goldman recounts how Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville, and Gunnar Myrdal each offered their own distinctive expositions of what made Americans special—and that these had little influence on how we understood ourselves until the great crises of the twentieth century intervened to demand a stronger basis for national unity.

In Goldman’s telling, Lincoln articulated the influential first wartime version of the creed, and his vision was in turn expanded and adapted by Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Although each emphasized different and long-standing ideas in our nation’s history, they all agreed that it was shared belief that could bind the people together. With the end of World War II, many agreed with Will Herberg that “the sanctification of national principles was the only way to draw together a people of diverse origins.” But creedalism foundered in the 1960’s on the twin shoals of the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam—and to men like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Reinhold Niebuhr, the gaps between creedal ideal and political reality proved too great to overcome.

By the 1980’s, creedalism saw what Goldman suggests was a nostalgic revival, led by Ronald Reagan, and its adherents launched one front of today’s culture wars over how we interpret American history. Little has changed today, with conservative creedalists arguing that if we can simply teach enough of American history and the most important thinkers and statesmen that crafted it, and in so doing form intellectually capable citizens, we might finally stop the threats to authentic Americanism posed by the left. But Goldman rightly thinks this asks too much of history:

Americans turn to history to explain who we should be. The most it can really tell us, however, is who we were. The culture wars continue because we want interpretations of the past to stand as proxies for political argument in the present. And that is a burden history cannot bear.

Advancing a carefully balanced pluralism, Goldman contends that while “covenant, crucible, and creed are all part of America… none exhausts its past or prospects.” One might ask, though, whether such careful balancing acts tend to emerge naturally in—or even appeal to—Americans.

So intense is this passion on the creedal right that their vision of Americanism tends to blind them to the obvious limits of the creed as a basis for unity. The creed cannot make moral citizens or keep even the creed’s most vocal advocates from excesses of partisan fervor—it may even exacerbate their ideological tendencies. Moreover, to the degree proponents of creedalism suggest every citizen must become a scholar of American political thought and history, it is unrealistic as a basis for unity. A deep adherence to creedalism has not built greater unity in the Republican Party, much less the nation; if anything, it has accelerated our recognition of how great the right’s disunity has become.

The Enduring Appeal of Symbolic Politics

At the outset of the book, Goldman explains his commitment to assessing his three traditions of thought as a scholar, which he tells us forms the core of his “suspicion of myth.” Even though we might acknowledge the limits of both creed and covenant with Goldman, he fails to grapple with why anyone still gravitates to such obviously faulty political faiths. And this presents a difficulty for the reader that wants to extrapolate from his categories to the present moment.

There’s a sense in which Goldman’s account tries to render these myths in functionalist terms—that is, he explains them as means to an end rather than something that offers meaning or fulfillment to the membership, and thereby misses why people care in the first place. Goldman concludes the book with an exhortation to moderation—to accepting that Americans are more fit to embrace a low but stable basis for the nation. Instead of lofty aspirations for unity and common purpose, we should look for “simple, substantive ideas that can unite us… rules of coexistence for people who otherwise don’t share much.” This modus vivendi rules out an expansive sense of the common good just as it demands we see pluralist conflict and disunity as deeply American. But we are also asked to see unity in this American pluralism.

Ironically, this seems to default Goldman into sounding more like a crucibilist than any of the other symbolic traditions he describes, looking to “a variety of overlapping and sometimes contending groups” as “the appropriate setting for cultivating particular virtues” of citizenship. On this account, our loyalty to particular communities will somehow generate the glue that will hold us together as Americans while also moderating the sharper points of contention between those communities that threaten to break us apart. The trouble with this wager is that there seem to be precious few “simple, substantive ideas” that unite us in the manner he desires—and a great deal of conflict over the fundamental truths that make our life together possible.

Goldman clearly grasps the ways that intense American creedalism has become an ersatz religion for some on the right, one that takes on an “ideological character” and a “quasi-religious orthodoxy.” The woke identitarians, too, share this religious character, a topic on which he remains silent. The scholarly hope for a moderate equipoise between creed, crucible, and covenant may simply miss a fundamental, dangerous truth about our polity, and perhaps every polity in our disenchanted age: Is it possible that these mythic extremes speak to a spiritual need that nationalism itself cannot fulfill?

While it offers an illuminating and thoughtful genealogy of American conceptions of nationalism, After Nationalism’s thoroughly diagnostic key leaves the reader hoping for a prescription. What is needed is a pathway toward a developing a humane sense of patriotism, one that leads us to prudently defend our land and laws for the twenty-first century. And to craft one, we must reckon with the idea that neither the broken remnants of a woke covenant nor a hollow appeal to American civil religion will do.