“To Make Disciples of All Nations”

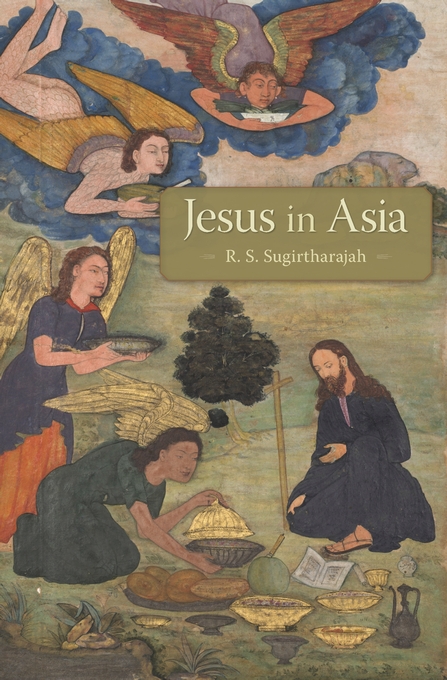

Those of orthodox (small “o”) Christian faith should expect to be taken aback by R.S. Sugirtharajah’s Jesus in Asia, a book that has just been published by Harvard University Press. But such readers who would put aside their surprise may well find the book’s depictions of Jesus over the centuries in various Asian countries fascinating—or at least entertaining, like a visit to a museum might be.

In his introduction, Sugirtharajah, Emeritus Professor of Biblical Hermeneutics in the Department of Theology and Religion at the University of Birmingham, laments that the study of Asian depictions of Jesus has been ignored in Western seminaries or, at most, confined to coursework in church history or mission studies rather than Christology. The same orthodox Christians who might find this book unnerving could easily inform him why this is. They would very likely inform him that they find these depictions of the Jesus of the Gospels heretical.

Consider it from these Christians’ perspective when we learn that, “The teaching of Jesus is encapsulated in the third liturgical Sutra, where four essential principles—‘no desire,’ ‘no piousness,’ ‘no doing,’ and ‘no truth’ . . . ” Such teaching bears resemblance to the Buddhist Four Noble Truths but none at all to the Gospel of the New Testament.

Also of great curiosity is that Hong Xiuquan, the leader of the Taiping Rebellion in the mid-19th century, “deleted the word ‘only’ where Jesus is spoken of as the ‘only begotten Son of God.’ ” Little things like the word “only,” to say the very least, mean a lot. Christologists wouldn’t have kind things to say about the deletion of this word.

There is a defensiveness in Sugirtharajah’s writing along the lines of we-Asians and they-Westerners, and it can be distracting. Common artistic depictions of Jesus looking Caucasian notwithstanding, linguists and geographers could affirm that, most technically, Jesus was in fact Asian, Bethlehem being in the far western part of Asia, and that he spoke Aramaic, a language classified as Afroasiatic. But I think we can assume that Jesus wouldn’t want his Asianness dividing East and West.

Sugirtharajah posits that “the first modern depiction of Jesus’ life was not written in the Christianized West, as is often presumed, nor was it composed in a European language nor even aimed at a Christian audience.” Rather, it was commissioned by the emperor Akbar. Really? Did no one so endeavor in all the centuries before Akbar, who lived from 1556 to 1605? The veracity of this would certainly depend on how one defines “modern” and “depiction” but I find the statement hard to accept using conventional definitions of those two words. I can’t help feeling that the author used some esoteric meaning of those words to justify his statement.

He concludes grandiloquently that, “Just as the Bible in Asia is not a stand-alone text but has to be read in conjunction with the religious texts of the East, so, too, Jesus has to be understood in relation to the region’s spiritual sages.” In this sentence, the three words, “has to be” are the little things that mean a lot. In fact, they mean the entirety of evangelical Christianity, which affirms the sole divinity of the Bible and which, furthermore, has quite a following in modern Asia.

Although orthodox scholars would not doubt that the spreading of the Gospel must necessarily adapt to local cultures, can it still be understood to be Christianity when the Gospel itself is adapted?

The intent of this book, which its author notes throughout, is to “extricate Jesus from his historical moorings so that he could live at any time, including in the present.” The entirety of Jesus in Asia holds that the need for such extrication to truly understand Jesus is self-evident. I for one did not find it so.

Let us consider what Jesus might think. How would the Christ respond to such portraits made of him? Would Jesus feel that He needed to be extricated from his historical moorings in order to live at any time?

To cite the words of Jesus himself in the Book of Matthew 28:19-20:

Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.

The words of the Great Commission do not directly address the questions posed above. But the timelessness of His commandment and its eternal import would suggest that Jesus wouldn’t need extrication from anything.