Our education, licensing, and entitlement policies are driving the young to socialist views which break sharply with America's political tradition.

Corruption on the Left

Peter Schweizer has become America’s foremost authority chronicling political corruption, with books ranging from Throw Them All Out and Extortion to Secret Empires and Clinton Cash. These exposés have led to follow-up investigations by the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and 60 Minutes, and even to Congress passing the STOCK Act, which prohibits insider trading by government and congressional employees. For Schweizer, this has turned into an unexpected career not only as an author and investigative journalist but as founder and president of the Government Accountability Institute.

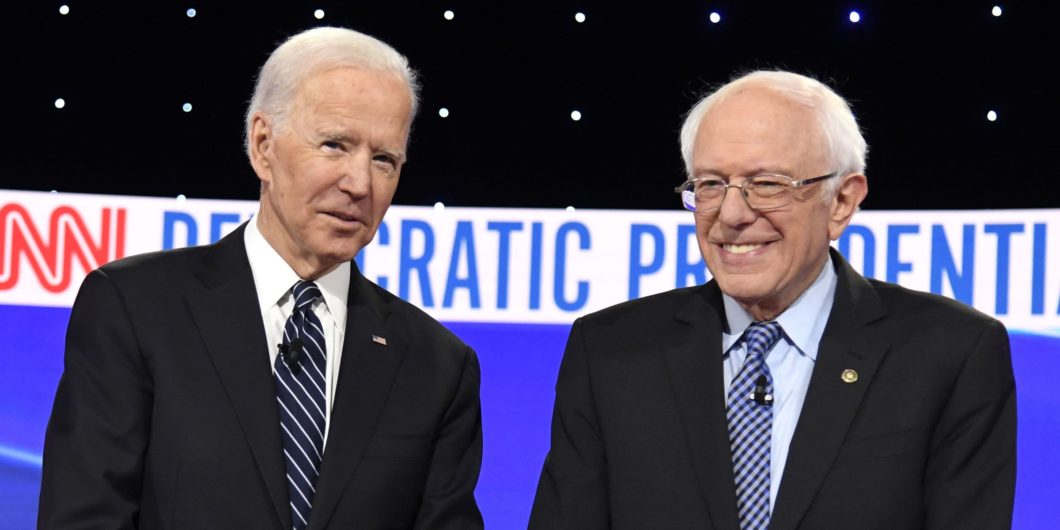

Schweizer has intrepidly detailed corruption at the highest levels of both the Democratic Party and Republican Party. His most recent work, Profiles in Corruption: Abuse of Power by America’s Progressive Elite, looks at eight leading liberals, many of whom tossed their hat into the ring for the Democratic Party presidential nomination: Kamala Harris, Joe Biden, Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, Sherrod Brown, Bernie Sanders, Amy Klobuchar, and Eric Garcetti. Some of these names may be surprising, while others obviously are not.

The book traverses 354 pages, roughly 80 of which are endnotes carefully documenting the book’s many shocking claims. When Schweizer narrowed down his choices of which progressives to focus on, he probably figured he had bona fide presidential contenders among several of them—Harris, Biden, Booker, Warren, and Sanders. He probably didn’t expect the quick exits from the Democratic race by Harris and Booker, nor the lasting power of Klobuchar. But he no doubt expected Biden and Sanders to hang around. Tellingly, the book’s two longest chapters go to Biden and Sanders, the two frontrunners. Upon close inspection, this seems less a prophetic projection from Schweizer than a simple case of following where the evidence leads.

I will offer some of the book’s highlights (or lowlights), then focus at length on the Sanders profile as an example of Schweizer’s meticulously researched accounts.

Power and Money on the Left

Schweizer’s profiles are tied together by a common theme: the confluence of power and money. While parroting the left-wing rhetoric of equality, the prominent figures he investigates all used their power both to protect their positions and to make money for themselves, their backers, and their families. As for Kamala Harris, Schweizer links her rise in national politics to her close ties with California’s corrupt political machine and reports that her tenure as a prosecutor in the state raised “disturbing questions about her use of criminal statutes in a highly selective manner, presumably to protect her friends, financial partners, and supporters.” Harris, he says, “covered up information concerning major allegations of criminal conduct, including some involving child molestation.” Schweizer has a similar assessment of Cory Booker: “his political climb reveals a politician who has leveraged his power for the benefit of his friends and supporters.” Booker has used that power to enrich family and friends.

Schweizer sees similarly stark abuses and excesses with Elizabeth Warren. Specifically, he charges that in the 1990s Warren “effectively leveraged her position working as a government consultant on bankruptcy issues to reap a rich financial harvest as a legal consultant for the biggest corporations in America,” with her family likewise benefitting. Like Bernie Sanders, Warren might make a big display bashing the rich, but she’s hardly averse to raking in some bucks for herself. “The fundamental contrast between what she presents herself to be and what she has done provide for remarkable contrasts,” says Schweizer.

Along with his report on Bernie Sanders, Schweizer’s chapter on Joe Biden is his most revealing. Biden has been part of American public life for nearly 50 years. The bookends of his career involve two personal tragedies: the heartbreaking loss of his first wife and daughter in an automobile accident in 1972 and his son Beau’s death from brain cancer in 2015.

Biden’s detractors will want to read what Schweizer has to say about his family members, as the tale of corruption here is a family affair.

Ironically, whereas much of the tragedy in Biden’s life has involved his family, so has the scandal and corruption. In this 2020 political season, we will hear far more from the Trump campaign about Hunter Biden than Beau Biden. But it might not just be about Hunter.

“The Biden family’s apparent self-enrichment depends on Joe Biden’s political influence,” writes Schweizer, “and involves no less than five family members: Joe’s son Hunter, daughter Ashley, brothers James and Frank, and sister Valerie.” (Biden has only two living children, Hunter, from his first marriage, and Ashley, from his second marriage to Jill Jacobs in 1977.) Biden, notes Schweizer, insists in “absolute terms that he never discusses family members’ business activities.” Based on Schweizer’s account, this might be a good idea.

Schweizer first reported on Hunter in his 2018 book, Secret Empires. He places Hunter on Air Force Two with his father flying to Beijing on December 4, 2013. The trip happened to coincide with an enormous financial deal that Hunter’s firm, Rosemont Seneca, was arranging with the state-owned Bank of China, run by the Chinese Communist Party. Approximately 10 days after the trip, Hunter’s Rosemont Seneca Partners finalized a deal with the Chinese government worth $1 billion. Yes, that’s billion. According to Schweizer, the deal soon mushroomed to $1.5 billion and now (according to the fund’s website) is worth over $2 billion.

Of course, China wasn’t the only country where Joe Biden’s son stood to gain significantly. There were those deals with Russia, with Kazakhstan, and with Ukraine. As to the latter, Schweizer details a meeting at the White House with Joe Biden on April 16, 2014 that was soon followed by Hunter’s appointment on May 13 to the board of directors of Burisma, the Ukrainian natural gas producer. Each of these board members was paid an astonishing $83,333.33 per month by Burisma, or a million bucks per year.

We are sure to hear much more about Hunter and Burisma in the months ahead. Biden’s detractors will want to read what Schweizer has to say about other Joe Biden family members as well. The tale of corruption here is a family affair, as it is with Bernie Sanders.

The Socialist Millionaire

Schweizer’s chapter on Bernie Sanders is scathing. Here we have a self-anointed champion of the working man, a fighter against the wealthy, against Wall Street, against those nasty “One Percenters.” Few presidential candidates ever have made such a big deal about how much money others have—which is not surprising for a lifetime socialist. Yet Schweizer’s depiction shows that Sanders doesn’t have any qualms about piling up his own wealth.

Maybe that’s partly because Sanders never had money until he was elected to public office in 1980. Prior to that, Sanders, who supported the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, and who had been a member of the Young People’s Socialist League in college, never seemed to find gainful employment. A failed carpenter, he literally struggled to keep the lights on. “When he couldn’t pay the electric bill,” remembered Nancy Barnett, an artist who lived next door to Sanders in the 70s, “he would take extension cords and run down to the basement and plug them into the landlord’s outlet.” The landlord grew tired of Bernie’s mooching and tossed him out.

Sanders sought economic salvation in the public sector. In 1980, after previous failed bids for public office, he ran for mayor of Burlington, Vermont and won by a mere 10 votes out of 8,650 ballots cast. He would use this position not only to pay the bills but to pad the pockets of himself and family members.

Shortly after winning the election, Sanders—divorced from his first wife—met a young mother named Jane Driscoll at his official victory party. They began dating and eventually married in 1988 (celebrating with a strange honeymoon trip to Yaroslavl, USSR). They became a team, not just personally but politically and financially.

In short order, Sanders appointed Jane, his new girlfriend, to head up the Mayor’s Youth Office, a volunteer position that suddenly became salaried, and was filled by Jane without any outside posting (as was customary) for others to apply. This special office was placed directly under Mayor Sanders’ command rather than the jurisdiction of the Parks and Recreation Department. After Bernie and Jane tied the knot, Mrs. Sanders got a hefty pay increase—which quickly became a matter of controversy to townspeople and the local press.

One shouldn’t begrudge anyone’s wealth. But Bernie’s is ironic, given that he has made a career begrudging others’ wealth.

As Schweizer notes, this was just the start for Sanders of an “established pattern of benefiting himself and his allies.” Jane aside, Schweizer details additional Bernie associates who gained from the Independent socialist’s handy nepotism, and not just at the mayor’s office. During Sanders’ long public-sector cruise from the mayor’s office throughout the 1980s, to Congress in the 1990s, the U.S. Senate in the 2000s, and two fully funded presidential campaigns in 2016 and 2020, he never again worried about where he would get his next dollar—it came courtesy of the public purse.

All along, Sanders would find ways to put his family on the payroll—via various creative “financial conduits to run cash to the Sanders family.”

Once elected to Congress, Sanders put Jane on the payroll in various capacities. She served as chief of staff, press secretary, political analyst, and even as a “media buyer” with an extremely generous commission percentage. On September 27, 2000, the Sanders family formed something called Sanders & Driscoll LLC, a for-profit consulting company run by Jane, her daughter Carina, and son David. It operated under two trade names, Leadership Strategies and Progressive Media Strategies. These entities were run out of the Sanders family home on Killarney Drive in Burlington. They never disclosed the income they received from these ventures, listing only “more than $1,000” on Bernie’s financial disclosure form. It is alleged that “Sanders doled out more than $150,000 to his wife and stepdaughter for campaign-related work between 2000 and 2004.” States Schweizer:

The Sanders family consulting business was at the headwaters of what would become a common Sanders move: use Bernie Sanders’s political position and power to provide income stream opportunities for the Sanders family. Later, as he set up his nonprofit organizations funded by his political supporters, he would again pay members of his family.

Moreover, Schweizer shows that these are some curiously profitable “nonprofits” that Sanders set up. They have been handsomely helpful to Bernie and his family. Schweizer traces a dubious trend going back to Sanders’ first failed nonprofit organization, the American People’s Historical Society, which Bernie launched in 1977, only to see its nonprofit status revoked. “It was the beginning of a trend that held for most of the Bernie nonprofits,” notes Schweizer.

Another perk of Bernie’s public profile in Vermont was Jane’s cushy job as president of Burlington College. This enabled Jane to slide more money to her daughter Carina, who had started the Vermont Woodworking School. Over merely a handful of years, the college funneled more than $500,000 to Carina’s woodworking school. Jane’s antics at Burlington College had the community up in arms. Mired in scandal, the college board of directors asked Jane to leave the presidency in 2011. She did, walking away with $200,000 in severance pay. As for the strained college, it collapsed, closing its doors in 2016.

And then there have been the books. Over the last five years, no senator has published as many books as Bernie Sanders. For one of them, titled Our Revolution, the anti-capitalist revolutionary received a staggering $795,000 advance. For another, Outsider in the White House, the Bernie 2016 campaign paid Sanders’ publisher $440,000 for copies to give to supporters and donors. The denouncer of the “ultra-rich” has done the same with other books.

Through all of this, Sanders has become a multi-millionaire. He and Jane’s annual income in 2016 and 2017 exceeded $1 million. Politico has referred to Bernie as a “three-home-owning millionaire with a net worth approaching at least $2 million.” Among his latest homes is one he and Jane bought with cash for $575,000 in the Champlain Islands, graced with 500 feet of lake beachfront. They summer there. In addition, in 2009 they dropped $405,000 on an attractive Colonial home in Burlington. The socialist couple also forked over $489,000 for a rowhouse in Washington, D.C.

Of course, one shouldn’t begrudge anyone’s wealth. But it is ironic, given that Bernie has made a career begrudging others’ wealth.

For his eye-raising profile of Sanders, and so many more, we should be grateful to the excellent research of Peter Schweizer. Here is an impressive book that sheds ample light on the shady activity it seeks to expose. The public owes Schweizer a debt of gratitude for showing that, despite the flashy, egalitarian rhetoric, there are sad and stark abuses of power by the nation’s progressive elite.