Debating Publius

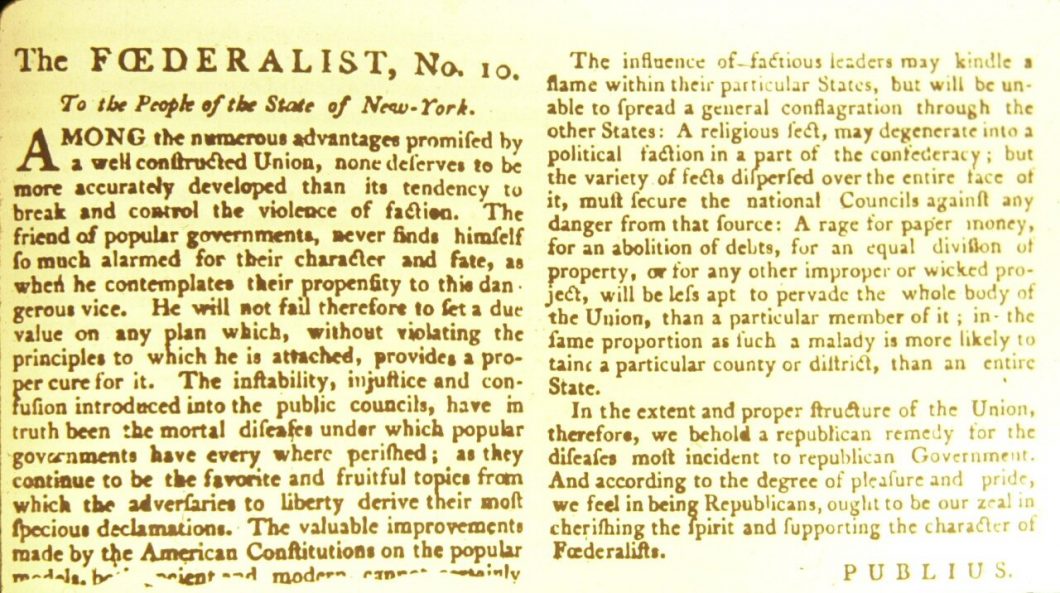

If the popularity of the musical Hamilton has contributed to a revival of interest in The Federalist in American popular culture and education, two significant political events over the last generation have also helped contribute to the continuing relevance of the work in American law and politics. The first was the resurrection of original intent or original meaning jurisprudence by the Reagan Administration in the 1980s as a counterweight to the liberal judicial activism that had dominated so much U.S. Supreme Court jurisprudence over the previous generation. The second was the Tea Party movement of a decade ago. Like the movement toward originalism spearheaded by President Reagan’s Attorney General Edwin Meese III and popularized by Judge Robert Bork’s 1990 bestseller, The Tempting of America, the Tea Party movement made the founders’ Constitution the touchstone of American constitutional law. And at the center of the founders’ constitutionalism was The Federalist, the 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pseudonym “Publius” in defense of the original Constitution.

Contemporaneous with these political movements was an academic movement over the meaning of The Federalist and its appropriate place in the American constitutional order. A number of the key figures in this parallel movement appear in the just released Cambridge Companion to The Federalist, edited by two well-respected scholars of the American founding, Jack Rakove and Colleen Sheehan. The Companion, which exceeds 600 pages, consists of 16 essays by prominent academics in the fields of political science, history, and law and runs the gamut of the ideological spectrum. As the editors note in their Introduction, The Federalist is thought by many, at least in political science, to be the consummate “exposition of the original meaning of the Constitution;” perhaps the best explanation of both the theory underlying the Constitution and its meaning by those who ratified it.

But historians disagree with political scientists. So Rakove and Sheehan propose. Being much more skeptical about whether The Federalist or the ratification debates actually captured the true state of public opinion in the late 1780s, historians doubt whether ideas prevailing at any time can fix the meaning of a written text like the Constitution. “The legal fiction of originalism might have its uses within the courts of constitutional jurisprudence,” the editors remark, “but it could never provide an adequate way to assess the true meaning of the Constitution. For historians the clock of constitutional time never stops running.” We might translate the dispute here in today’s vernacular to the debate between constitutional originalists and those who advocate for a “living constitution,” a constitution susceptible to ever-changing meaning as history progresses.

To some extent this is how the contributions to the Companion read. There are those who view The Federalist as indeed the consummate guide to the Constitution. Others, like the opening essay by David Siemers in defense of the Anti-Federalists, pooh-pooh it. Indeed, one of the more mysterious features of the Companion is that its very first essay is from front to back a broadside against Publius’ work. “Instead of a dispassionate, reasoned analysis that stood far above others,” Siemers begins, “The Federalist stood squarely in the fray—a devoted partisan document with a tendency to vilify opponents, to shade and to spin as much as to inform.” Siemers has almost nothing good to say about The Federalist or its authors. Of Hamilton’s response to public sentiment suspicious of the Constitution providing federal training, equipping, and deputizing of state militias Seimers demurs: it amounted to “an exasperated screed.” What was worse, Publius failed to anticipate what American government actually became. The Anti-Federalists had critiqued The Federalist’s theory of republicanism for its lack of descriptive representation and that lack is evident today in Congress, “particularly in terms of race and gender.” And in apparent agreement with two scholars who conclude that “American government is not a democracy but an oligarchy,” Siemers offers that “this was the precise fear articulated by many Anti-Federalists.”

A more charitable reading of The Federalist and of Hamilton is found in Max Edling’s exposition of how Hamilton’s Federalist numbers on security, war, and revenue anticipated what the federal government became shortly after ratification. Edling underscores that until recently there has been an overwhelming preference in Federalist scholarship for the Madisonian elements of the work, a development that Edling, like other contributors to the Companion, attributes to Charles Beard’s Economic Interpretation of the Constitution (1913)—the text that made Madison’s Federalist 10 Publius’ centerpiece. For the last century commentators have tended to focus on Madison’s discussions of the problems of faction and interest-group politics, the hazards of majority rule and protection of minority rights, separation of powers, and other aspects of the Constitution’s institutional process. Yet in the case of the Constitution’s protection of individual rights against the impositions of overbearing state legislative majorities, Edling writes, “it was only when the Supreme Court began to actively strike down southern laws of discrimination after the Second World War that the Madison vision was fully realized in the United States.”

By contrast, Hamilton’s emphasis in The Federalist on the need for an improved fiscal-military state that would provide the federal government with the financial and military wherewithal to improve national security were largely in place by 1795. And those remedies were provided in a manner consistent with limited government constitutionalism; there were only three major executive departments—State, War, and Treasury—and although small, they were effective.

Edling qualified that despite the dominance of pro-Madison scholarship on The Federalist over the last decades a noticeable shift has begun to take place that has focused more on the founders’ concerns with international relations and federalism. The two chapters that follow Edling’s in the Companion focus on precisely these issues. NYU law professors David Golove and Daniel Hulsebosch contend that despite the many themes of The Federalist “foreign affairs remains its ultimate subject.” Michael Zuckert, by contrast, proposes that “federalism seems to have been the central issue in the debate over the proposed Constitution,” as both the title to Publius’ work and the name of the Constitution’s opponents suggest.

Both of these chapters provide compelling interpretations of underappreciated aspects of The Federalist; Golove and Hulsebosch, for instance, point out how those powers over foreign affairs placed in the federal government’s hands—powers over diplomacy, war, peace, and commerce—were as important to solving America’s domestic problems as they were to solving problems in international affairs; Zuckert highlights that The Federalist’s primary task was to convince the American public why the new federalism of the Constitution was so much better than the old federalism of the Articles of Confederation that had proven so ineffective. Again, promoting national defense and internal domestic order were central issues here, themes we find replicated in later essays in the Companion.

For readers of Law & Liberty one of the more interesting features of the Companion will likely be the extensive discussion of the influence of the Scottish Enlightenment on the authors of The Federalist. Edling, Golove, and Hulsebosch, discuss this aspect of The Federalist’s constitutionalism as do later essays by Jon Elster on Publius’ political psychology and Paul Rahe’s chapter on the influence of Montesquieu, Hume, and Adam Smith on The Federalist’s philosophy. Rahe in particular does an excellent job of dissecting the details of the political philosophy of Montesquieu and how that philosophy, along with Hume’s and Smith’s influence, would crystalize in the singular commercial republican theory and institutionalism of The Federalist; the latter being critical to keeping the multiplicity of interests and sects of the large commercial republic embraced by the Constitution stable and secure.

Professional political science has rendered itself increasingly irrelevant to modern American politics.

Alan Gibson adds in his chapter on Madison’s Federalist 10 that the rhetorical tactic of The Federalist was to identify the instability of the ancient Greek polis with the state governments dominant under the Articles of Confederation. The violent eclipse of the polis due to its factious pathologies, especially majority factions, meant that Montesquieu’s orthodoxy that only in small republics could the public good be known and cohesion maintained would have to be abandoned. But Madison’s multiplicity of interests theory, Gibson implores, was not an embrace of modern pluralistic or interest group theory. Madison believed that there was indeed a common good beyond the mere clash of interests that could be discerned through an impartiality principle. That principle would be established through an extensive territory that incorporated a multiplicity of interests, large electoral districts that promoted elite representation geographically removed from constituency pressures, and other institutional measures, all of which were intended to address the “great desideratum” the Convention faced regarding how to achieve legislative impartiality while maintaining popular control of the government.

Other chapters devoted to Madison further develop themes introduced by Gibson. Colleen Sheehan expands on how Madison saw the extended territory and federal system of representation under the Constitution as a way to cultivate a sophisticated commerce of ideas within American society. In response to the likes of Martin Diamond who viewed the Constitution as promoting the low but solid ends of security and material prosperity, making “mediocrity great” as Sheehan puts it, Sheehan counters that the ends of American constitutional government were much more elevated, concerned with the high principles of self-government and justice.

Larry Kramer’s chapter also seeks to salvage Madison from the opprobrium that he was an undemocratic elitist who wanted to curb the power of the people. On the contrary, Madison was “a committed republican who believed in popular government and believed that the people must control the government and law at all times.” This included controlling constitutional interpretation. Madison would have never countenanced today’s doctrine of judicial supremacy where the Supreme Court gets the final say over the meaning of the Constitution. Giving such a power “to a mere agent of the people, worse, an agent structured and designed to be as unaccountable as possible” was “something Madison could never accept.”

Jack Rakove adds that Madison had an “indoors” teaching, his well-known institutional doctrine, as well as an “out-of-doors” teaching, his much less well-known political sociology about the importance of the ever-swirling passions, opinions, and interests of the people. It was this latter innovation, seeking to balance society’s passions and interests—what belonged “to the people out-of-doors”—that Rakove proposes was the most important and underappreciated aspect of Madison’s political theory.

The Companion concludes with essays by co-authors John Ferejohn and Roderick Hills on Publius’ political science and by Harvey Mansfield on the republican form of government in The Federalist. Mansfield’s chapter criticizes present-day political science for its rejection of the formalism of The Federalist that “made liberalism popular and republicanism viable.” In addition, Mansfield expresses skepticism about those who cherry-pick isolated passages from Hamilton’s or Madison’s contributions to The Federalist and then combine these with earlier or later statements by the authors to demonstrate The Federalist’s purported “split personality” or incoherence (something a number of the contributors to the Companion indulge in).

Sheehan shares many of Mansfield’s concerns about contemporary political science. Both highlight that today’s discipline is plagued by the fact/value distinction that holds that real science can only deal with facts, not values. The result of this narrow disposition, Mansfield suggests, has not only been a discipline overwhelmed by “modeling” facts of behavior in methodological disputes over frequently petty issues but a profession that cannot offer advice or pass judgment on even the most elementary political questions that most citizens judge everyday.

Accordingly, professional political science has rendered itself increasingly irrelevant to modern American politics. What is worse, presuming, as Sheehan puts it, that “human ‘reason’ is merely a pretense for personal values, self-interest, male dominance, and/or power,” contemporary political science promotes a moral relativism that is the antithesis of The Federalist’s teaching regarding human nature, a teaching which “recognized that what is distinct about human beings is their capacity to reason about true and false, just and unjust, right and wrong.”

A number of other essays that I have not mentioned here on John Jay’s contributions to The Federalist, by Quentin Taylor, The Federalist on Congress, by Greg Weiner, Publius on monarchy, by Eric Nelson, and Hamilton on the judiciary, by William Treanor, round out the Companion’s extensive treatment of Publius’ seminal work. An exceedingly fastidious critic might complain that the Introduction to the Companion expresses a little too pro-Madison and anti-Hamilton a persuasion and that, similarly, the Companion as a whole tends to skew more towards interpretations of Madison’s contributions to The Federalist rather than Hamilton’s, even though Hamilton wrote almost twice as many numbers as Madison. But who is counting?

The defects of the Companion are few while the richness of the essays and the comprehensiveness of their analysis of The Federalist is a reminder not only of just how different the founders’ political science was from the political science of today but how much more capacious their constitutionalism was. Rakove and Sheehan are to be commended for putting together a volume that addresses an old text in way that reminds us what a faithful companion Publius was to the Constitution and will continue to be well into the future.