Oliver Wendell Holmes was wounded three times on the battlefield, and his Civil War experiences affected his outlook and Supreme Court jurisprudence.

His Truth Marching On

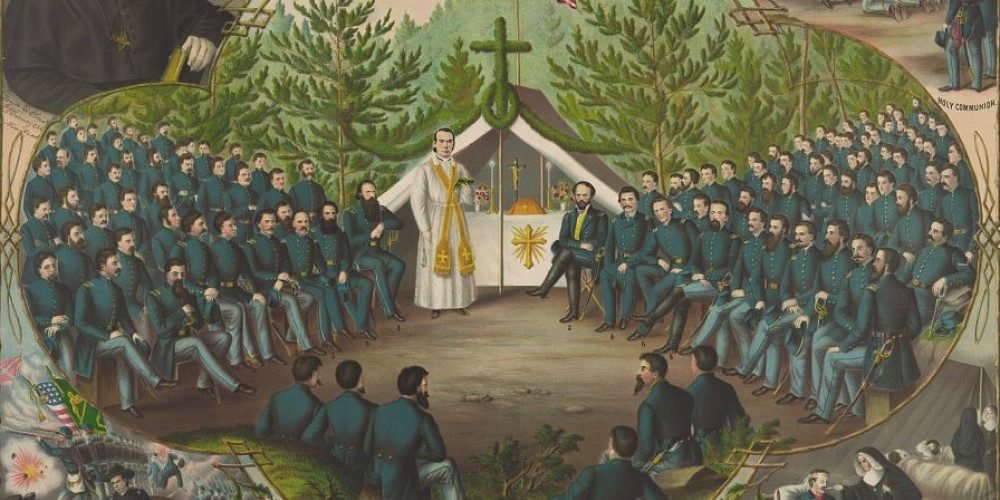

James P. Byrd opens his A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood: The Bible and the American Civil War with Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address. The sixteenth president famously observed that Americans “read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.” This is a fitting opening for a book that sets out to explain how Northerners and Southerners used Christian scripture to sustain their cause in the public religious realm, motivate their respective peoples to continue fighting, and justify in the eyes of the Almighty a war that eventually cost 800,000 lives. Byrd’s book treats the Christian scriptures not as a set of historical or even strictly religious texts, but as spiritually pulsing words pushing its readers—be they soldiers, civilians, or ministers—to action in a variety of different ways. The Bible, Byrd argues, was not simply a compilation of texts. It was “text in action—spoken in sermons, read in devotions, printed in newspapers, and more.” In this sense, the work Byrd offers is a quintessentially American story of scripture’s use, which is fitting to understand an event that Robert Penn Warren called the central event of the American imagination.

The moral and religious fervor of the Civil War Era conjures Harper Lee’s wry observation in To Kill a Mocking Bird that “Sometimes the Bible in the hand of one man is worse than a whisky bottle in the hand of (another) . . . There are just some kind of men who—who’re so busy worrying about the next world they’ve never learned to live in this one, and you can look down the street and see the results.” Bible-infused Evangelical moral polemics resulted in catastrophic social and civil destruction and the seed of imperial bureaucracy. The positive outcomes of the Civil War, the most important being the end of chattel slavery, were accomplished not by abolitionist pastors waving their Bibles but through executive fiat—the Emancipation Proclamation—and the decision to arm free Black men to fight for the liberation of the enslaved. Nonetheless, the Bible was an ever-present companion to soldiers, wives on the homefront, moral reformers, religious clerics, politicians, and others. Byrd’s work, even if only to catalogue scripture’s use across northern and southern society in the war, is a noble effort.

A Fiery Gospel

This book might have been more aptly subtitled “The American Bible and the Civil War.” Even a cursory look at the contents and a quick run-down of the denominational affiliations in the opening pages shows that the Bible invoked by Byrd is that of Evangelicals or Revivalists in the United States during the first half of the 19th century in the United States. Quotes about baptism and blood are scattered across the contents page and we may safely assume, given the origins of the quotes, that these are not allusions to sacramental baptisms or bloody images of the crucified Christ found in sacramental churches. No, these are the blood and baptism of American revivalism, and the Bible of the Civil War Era in Byrd’s work never strays far from the hermeneutic embraced by Baptists and Methodists influenced by the heady revivalism of the Second Great Awakening. Most of the enslaved Christians in the United States, Byrd notes, identified with these two aforementioned traditions, and statistics show that by 1860 so did a majority of white Americans.

The book is arranged chronologically. The early chapters cover the period that preceded the Civil War. Here, William Lloyd Garrison‘s Liberator makes an appearance. The Massachusetts abolitionist sprinkled Biblical allusions into his paper’s tirades against southern slavery. But like many Americans he also found the Christian Bible annoying; it sometimes didn’t say what he wanted it to say, and it sometimes said what he didn’t want it to say. Scripture’s usefulness played an important role in political sermons, but those like Garrison did not always use strict textual recitations. He especially struggled with the notion that the entire Bible was divinely inspired and so he often paraphrased texts for abolitionist purposes. In particular, he disliked the Pauline epistle to the Romans, which he thought clashed with the peaceful tenor of the New Testament. Byrd writes that Garrison’s selecting of which parts of the Bible were divinely inspired and which parts were not made the abolitionist an anomaly in the Early Republic. Garrison, says Byrd, “sounded radical to a lot of Americans who only wanted to hear the Bible was fully true.” Garrison’s temporalizing regarding divine inspiration, however, was consistent with textual criticism especially among New England abolitionists who treated scripture increasingly as a form for moral catechesis and social reform rather than God’s inspired and inerrant Word.

The chapters covering the first two years of the war focus largely on how combatants appropriated scripture to justify the respective war efforts. Southerners used scripture to justify secession, slaveholding, and their military effort to leave the Union. Northerners used scripture to justify unionism, wage labor, and the Federal efforts to end the slave rebellion. Robert Dabney, a Virginia Presbyterian, evoked the accounts of King David in the Book of Samuel as an example of a patriot king who made difficult choices that pitted brother against brother. The students at Hampden-Sydney would have understood the allusion to families splitting over the question of secession versus union. Northern and southern Unionists—clerics and politicians—appealed to Romans 13 to urge Christians to obey civil authorities which, in their reading of scripture, meant the United States government.

Most of the clerics and observers in the book were Protestants, but Byrd makes the important point that although Protestants dominated the United States in the Early Republic, the appeal of the Bible was not limited to Protestants, Christians, or even the Abrahamic faiths. As wide as the Bible’s appeal might have been in 1860, Byrd argues that most Americans had a common-sense approach to biblical interpretation and reading. This textual approach was joined with a belief that scripture was indeed a book that enlivened the faith of the reader—a hallmark of the Evangelicalism and Revivalism of the time. The imprint of these two movements is apparent throughout the text but especially so when it was used by writers to press the idea of a societal mission on respective audiences. King David, the prophet Samuel, Esther, and other figures from the Hebrew scriptures gave Civil War Americans examples of holy people who fulfilled specific holy causes. And Southerners and Northerners both viewed the Civil War as a holy cause.

Terrible Swift Sword

While the revivalism of the middle of the 19th century is readily apparent throughout the narrative, Byrd offers a comprehensive treatment of soldiers, politicians, and other observers as they interacted with biblical concepts like providence in the scriptures. The belief that God had a purpose for Americans in the North and South during the war was not limited to Calvinists wedded to a particular notion of God’s sovereign will. Christians of all types sought confirmation for some sort of divine purpose in the pages of scripture. Archbishop John Hughes, Roman Catholic Archbishop of New York, saw God’s providential hand in the outworking of the conflict. So too did thousands of Protestant ministers across the North and South during the war. Byrd argues that Northerners’ experience of military setbacks during 1862 and early 1863 convinced many of them that the war was a divine punishment. The spiritual failures of the nation could not be reduced to one section: Northerners looked to the Bible to discover how they might satiate the divine wrath being poured out on them in the form of defeat by the hands of Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

God’s divine vengeance, in the minds of many Northerners, took the form of soldiers tramping through southern farms and towns.

Lincoln’s musings on scripture come to the forefront of the narrative in the chapters on the Emancipation Proclamation. When it went into force at the beginning of 1863, it made the destruction of slavery in the South an explicit war aim. Slavery and southern society increasingly appeared in sermons of northern ministers, and what had been a war of rebellion become a war against godless un-American aristocrats bent on enslaving humans loved by God. No longer was scripture used merely to show why Southerners failed in their basic duties towards the magistrate. Increasingly, it was used to illustrate the innate wickedness of southern society and to justify a hard war against the South.

Northerners appealed to Ephesians 6 to argue that Southerners broke the Bible’s basic admonition to childlike submission to their paternal governors. Southerners of course used the same chapter to argue for the submission of slaves. By the middle of the war, Southerners transformed in northern polemics from willful children in need of correction to the rebellious and unrepentant people of God in Jeremiah 8 who not only needed but deserved God’s judgment. One Presbyterian divine in Pittsburgh declared that war was not simply against the South; it was also against Satan and any force that might do anything to weaken the government of the United States.

Biblical revenge and the place of anger in scripture played a role in how soldiers reacted to their enemies. Northern civilians dealt with how to approach fury biblically in the wake of atrocities like the Fort Pillow massacre and the Federal liberation of the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Statements from scripture where God appeared to reserve vengeance to himself—Deuteronomy 32 and Romans 12—were interpreted to allow the Union army to become a tool of divine judgment. God’s divine vengeance, in the minds of many Northerners, took the form of soldiers tramping through southern farms and towns. Northern ministers also invoked Romans 13 where St. Paul declared that magistrates were avengers who rightfully carried out God’s wrath on wrongdoers.

Northern anger at southern wrongdoing only increased after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on 14 April 1865. Lincoln’s assassination elicited more than anger. Fear, grief, fury, and uncertainty, noted Byrd, all became psycho-emotional constants for the northern citizenry. Lincoln quickly became a martyr for the Union, and the fact that his death fell on Good Friday meant that sermons on Easter mentioned his murder in conjunction with Biblical text across the Union. Byrd found that most of those sermons used texts from the Old Testament.

A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood is well-researched and covers a wide variety of themes comprehensively. The appendix of Bible verses most often cited in the work is a helpful tool for scholars and students of religion in the Civil War Era. The book’s weaknesses are more stylistic than methodological. The lack of a unifying thesis and the noble attempt to research so wide-ranging a topic and the Bible itself in the Civil War means that the work sometimes reads more like a collection of vignettes than a monograph. Topics that are in vogue, particularly race and slavery, receive an obvious premium in the book, but Byrd also does not offer much that is new with regards to thematic questions. Noted divines of the era are also surprisingly absent. Virginia’s loquacious Episcopal bishop William Meade is consigned to a footnote. Charles Hodge, perhaps the most important northern Protestant theologian in the 1860s, shows up on only one page.

The Bible’s interaction with moral and political philosophy also does not receive wide-ranging coverage. Perhaps more importantly for readers interested in the interaction of religion, law, and politics, the debate over the legacy of Locke and Hobbes among Protestant churchmen in the years of the Civil War would have been a fascinating inclusion in an already worthwhile work of history. None of these criticisms, however, detract from what is a comprehensive work of history that provides a broad and well-researched understanding of how the Bible figured into the lives of Americans in the Civil War Era.