Churchill understood that popular sovereignty poses hazards for the very liberty of which popular sovereignty is an expression.

History in Black and White

With the volume Red, White, and Black: Rescuing American History from Revisionists and Race Hustlers, the incomparable academic, community leader, and social entrepreneur Dr. Robert Woodson announces the founding of his latest initiative, “1776 Unites.” Woodson describes this initiative as a “black-led movement of scholars, grassroots activists, and other concerned citizens who believe America’s best days lie ahead of us.” He and his colleagues “focus on stories that celebrate black excellence, reject victimhood culture, and showcase African-Americans who have prospered by embracing America’s founding ideals.” They will share these stories through curriculum supplements for primary and secondary school students. They aim, at least in part, to combat the culturally and politically debilitating narrative of black victimhood being disseminated by the New York Times “1619 Project.”

Red, White, and Black comprises more than two dozen essays that address the theme of African American self-reliance. Lucas Morel explains in the Foreword that the volume chiefly focuses on “what black Americans have the power to do for themselves, their neighbors, and their country.” Some of these essays detail heroic achievements by blacks throughout American history. Stephen L. Harris recounted the story of “Harlem’s Hellfighters,” an all-black National Guard unit honored by the French government with the Croix de Guerre for valorous service in the Meuse-Argonne offensive in World War I. Harris also contributed an essay honoring Alice Coachman who, in 1948, became the first black American to win an Olympic gold medal. Woodson and John Sibley Butler detail several black entrepreneurial successes, including that of Biddy Mason who had been born into slavery, but in freedom amassed a fortune in California real estate and became a philanthropist. Other essays contain personal testimonies about the power of self-reliance. Carol Swain describes her journey from a childhood of privation to earning a doctoral degree and becoming an Ivy League professor. Dean Nelson tells of his journey to having become a minister and leader of several non-profit organizations.

Nelson’s essay, in detailing his triumph over the racism of “ignorant white people,” suggests the difficulty of maintaining a narrative of American history that transcends race, and it demonstrates the need for a project like 1776 Unites. Even in his criticism of the 1619 Project, Nelson notes that he and most of his black classmates learned “white history.” Though he clarifies that “[l]earning ‘white history’ in school did not cause any of us to believe we were inferior to anyone,” Nelson’s distinction makes clear that he did not identify with the (now dated) textbook version of American history on which many of us were raised. Nor has his rejection of the 1619 Project led him to embrace that triumphant account of American history that many of us, drawing upon the judgments of multiple eminent and prize-winning (white) historians, hold to be self-evidently true. Instead, Nelson explains that his real education was found in “black achievement-oriented reading material,” evidently of the kind that 1776 Unites intends to provide.

Many of us revere our Founding Fathers for having granted us freedom as our birthright. Now that this inheritance has been spent, let us reconsider our Founding Fathers in light of the black Founding Father, Frederick Douglass.

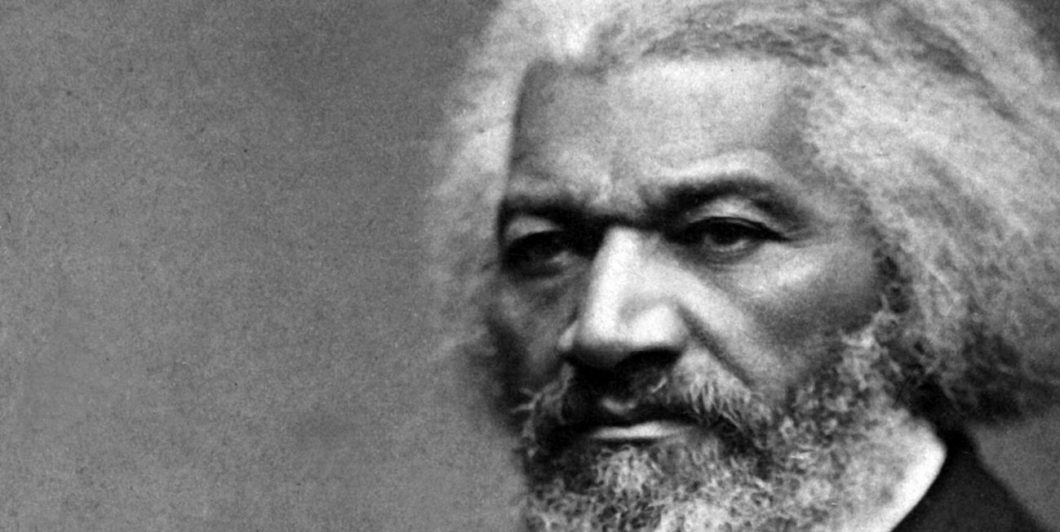

Frederick Douglass

If this volume reminds us of the gap between white and black history, it also reminds us of one black American who plays a prominent role in both—Frederick Douglass. Indeed, Douglass gets the first word in this volume (over Abraham Lincoln) and the last. For many white Americans, Douglass demonstrates that blacks embrace the themes we have embraced in American history. In this vein, contributor Stephanie Deutsch, citing prize-winning historian David Blight, finds Douglass to be the most “eloquent” exemplar of a national “evolution [that] has been guided by faith in the rule of law, by respect for our founding principles, by optimism, and by powerful voices of reason.”

This is true as far as it goes, but we should not forget that Douglass, too, distinguished between white and black history. “What, to the American slave,” he pointedly asked, “is your Fourth of July?” In dedicating a memorial to Abraham Lincoln, Douglass recalled that Lincoln “was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man. He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.”

White history may honor Douglass for his sober rationality in defense of justice, but some black authors in this volume find Douglass’s appeal in his spirited response to injustice. Yaya J. Fanusie admires Douglass as having been “struggling for blacks. . . .” Dean Nelson marveled at how Douglass “demanded respect.” To their credit, and to everyone’s benefit, these authors do not claim to deprive white history of this hero. Fanusie insists that Douglass was not fighting for “blackness” (a concept that she, as a Muslim, denounces as idolatrous). Nelson said nothing about Douglass’s race, but remarked simply, “What a man!”

Indeed, anyone who has ever read Douglass’s autobiographical account of his fight with his so-called master, Mr. Covey, will immediately share Nelson’s awe at Douglass’s courage. Covey caught Douglass unaware, dragging him out of a hay loft and tying his legs so he “could do as he pleased.” With no one to rely on for protection but himself, Douglass resolved to fight. “I seized Covey hard by the throat; and as I did so, I rose.” Covey “trembled like a leaf,” and called for assistance. Douglass handled the second assailant as well as the first, giving him “a heavy kick close under the ribs.” With his accomplice incapacitated, the terrified Covey asked Douglass if he intended to continue resisting. “I told him I did, come what might; that he had used me like a brute for six months, and that I was determined to be used so no longer.” Douglass recalls that they continued fighting for two more hours before Covey relented. In six more months of working for Covey, Douglass was never again threatened physically.

Douglass recalled this fight as being “the turning point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived in me a sense of my own manhood.” Douglass’s manly defense of himself is the ultimate example of self-reliance, even as it represented an incident of the threat our founding fathers most greatly feared—slave rebellion.

Despite this, or because of this, Douglass has retained a place in both black and white history because he, like our own revolutionary fathers, asked for nothing more than liberty, would accept nothing less, and used violence only as a means for securing his liberty and not as a means for avenging his subjection. If 1776 Unites can establish Douglass, on these grounds, in the hearts and minds of young black Americans as their Founding Father, as a full and rightful heir to our nation’s founding, and as an unparalleled exemplar of our nation’s civic virtues, this project will do immeasurable good.

Culture and Class

Frederick Douglass is the leading man of this volume, but the chief supporting character is the African American father. Several of the authors reported having strong fathers who refused to allow them to lose faith in the face of discouragement or resistance. Shelby Steele explained that when he was a young man, convinced of America’s racism and of the need for black or African nationalist alternatives, his father—whose own father had been born into slavery—cautioned that the younger Steele “shouldn’t underestimate America.” Conversely, this volume also points out that where fatherly insistence upon self-reliance is absent, social pathologies of truancy, crime, drug abuse, and childbirth out of wedlock are present. Several of the authors refer to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy to demonstrate how the absence of strong fathers is responsible, in white communities as well as black, for many of the social and cultural problems that are often attributed in black communities solely to racism.

Contributing author Clarence Page was raised, like Vance, in the Rust Belt town of Middleton, Ohio. Like Vance, he has witnessed the disappearance of working-class jobs and the consequences of this economic change on working class families. Page agrees with Vance that too many of these families, white and black, have responded not with manly self-reliance but with “learned helplessness.” This may be true, though it shades a bit close to victim-blaming. Still, if Page may be too harsh on the white working class, this reveals that whites may also have been too unsympathetic to the desperation of blacks stuck in poverty. He is right to conclude, “Americans need to desegregate our poverty discussion to learn across the lines of race and class the true causes of poverty and inequality. . . .”

This theme of poverty and inequality is a reminder that, while America has always known inequality in terms of intractable (if not necessarily irreconcilable) differences of race, we have scarcely known inequality in terms of irreconcilable differences of class. Yet the rise of what has aptly been called “neo-feudalism” portends that inequality, in the form of massive concentrations of capital and the hollowing out of the middle and working classes, is the unavoidable future of our nation. The fealty demanded by our neo-feudal ruling class may differ in substance from what was demanded in the past, but it still requires vassals and serfs to kneel in submission. Any who dare to demonstrate the manly spirit of self-reliance exemplified by our Founding Fathers in refusing such submission will soon come to know what it means to be treated as a second-class citizen, and even as somehow less than human.

1776 Unites may never succeed in uniting blacks in a full celebration of white history. Instead, the volume Red, White, and Black can help white Americans set aside the triumphalist view that tacitly frames our national story as the first chapter of the end of history, in which our nation’s Founders established just and rational principles of government that apply equally to all individuals in all places at all times. The experiences detailed in this volume can give us the courage to embrace the harsh truth from black history that true freedom is always and everywhere the product of struggle.

Many of us revere our Founding Fathers for having granted us freedom as our birthright. Now that this inheritance has been spent, let us reconsider our Founding Fathers in light of the black Founding Father, Frederick Douglass. As much as any of our white Founding Fathers, and even more so, he embodied the American virtue of manly self-reliance, refusing to kneel to his self-professed superiors and demanding their recognition of his rights even through the use of force. We may need his example sooner than we think.