History's Undying Penalty

During the 1880 Lent term at Cambridge University, school commissioner Joshua Girling Fitch delivered a series of lectures sponsored by the new Teachers Training Syndicate. In the last of these lectures, Fitch reflected on the place of morality in the teaching of history. “As to History,” he said, “it is full of indirect but very effective Moral teaching. It is not only as Bolingbroke called it ‘Philosophy teaching by examples,’ but it is Morality teaching by examples.” For a reformer like Fitch, history inspired youth with “the echoes of far-off contests and of ancient heroisms”—the grand drama of English history that featured the heroic Philip Sidney, the bishops who resisted James I, and Wolf dying gloriously on the Plains of Abraham. “As we realize these scenes, we know that this world is a better world for us to live in because such deeds have been done in it; we see all the more clearly what human duty and true human greatness are, and we are helped by such examples to form a nobler ideal of the possibilities even of our own prosaic and laborious life.”

These last words reappeared in the voluminous, multi-lingual footnotes to Lord Acton’s 1895 Inaugural Lecture as Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge. They were meant to bolster Acton’s claim for the place of moral judgment in the writing of history. “But the weight of opinion is against me,” he feared, “when I exhort you never to debase the moral currency or to lower the standard of rectitude, but to try others by the final maxim that governs your own lives, and to suffer no man and no cause to escape the undying penalty which history has the power to inflict on wrong.”

This righteous desire to hand down verdicts on the past is one of the defining marks of what a generation later Herbert Butterfield called “Whig” history. His 1931 Whig Interpretation of History, still in print after 90 years, begins with the problem of the historian seating himself on the judge’s bench: “It has been said that the historian is the avenger, and that standing as judge between the parties and rivalries and causes of bygone generations he can lift up the fallen and beat down the proud, and by his exposures and his verdicts, his satire and his moral indignation, can punish unrighteousness, avenge the injured or reward the innocent.” Notably, the words “lift up the fallen and beat down the proud” come from Anchises’s prophecy of Rome’s divine mission in Virgil’s Aeneid (Book VI), the very lines St. Augustine in the City of God four centuries later turned against Rome’s presumption in claiming God’s prerogative of justice for itself.

All of this may seem remote from problems of contemporary historiography, but it is not. If we think that Whig history is merely a quaint relic of the Genteel Tradition in Anglo-America culture that died once the twentieth century killed off innocence, optimism, and faith in progress, we are mistaken. Butterfield wrote about the “psychology” of the Whig historian, the habits of thought that shape his principles of selection and exclusion, that set the arc of his over-dramatized narrative, that catch him in pre-cut patterns, repeating the same stenciled design over and over. Butterfield’s insights are still relevant no matter how the togaed historians drape themselves ideologically today.

Academic historians busy constructing the new grand narrative of racism bear all the marks of the old Whigs. They keep one eye on the present, they search for origins rather than mediation points, they choose evidence that fits their assumptions, they moralize relentlessly, and believe they are on the right side of history. While Whigs a century ago looked for who to praise for the blessings of the present, today’s Whigs look for who to blame for the horrors of our time. They act as prosecuting attorneys addressing a jury of readers, summing up the evidence for their side, and pushing for a guilty verdict. No balance. No measure. No proportion. A reader, waiting in vain for the phrase “on the other hand,” becomes exhausted under the accumulated weight of sin and guilt. If he fails to convict, he must be part of the problem or at least blind or naive.

Taylor is a moral monist, and America must be judged from beginning to end by some future ideal of equality defined by the just distribution of wealth and power.

The University of Virginia’s Alan Taylor is a prolific author who writes extremely well. He has twice been awarded the Pulitzer Prize in history: in 1996 for the micro-history William Cooper’s Town and in 2014 for Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832. His latest book, American Republics, is the third in a series that began with American Colonies (Penguin, 2001) and continued with American Revolutions (Norton, 2016). Perhaps his next installment will be called American Nations or American Empires.

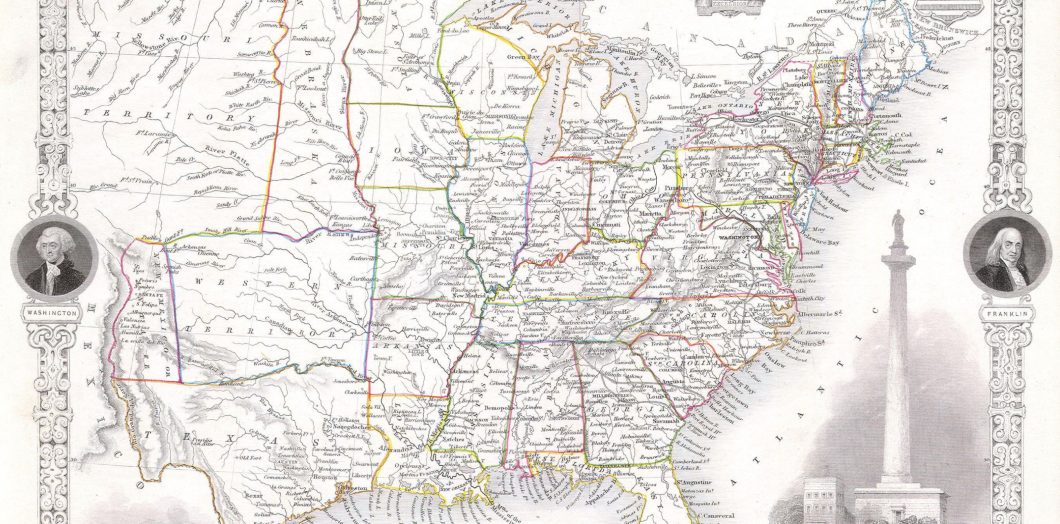

Taylor is to be commended for placing American history into a global context of competing Empires and struggling republics. American Republics is kaleidoscopic “continental history,” keeping in play the stories of Britain, France, Spain, Russia, Canada, and the tumultuous Mexican republic. The early United States takes its place geographically, politically, economically, culturally within a vast North America of competition and more than a little confusion. Taylor takes full advantage of recent trends in transatlantic history, multiculturalism, and race, class, and gender, but I think he misses how attentive to the larger imperial and cultural context historians once were. We did not have to wait until the 1960s for historians to see the wisdom of this perspective. Nineteenth-century historians were quite adept at doing so. The multicultural, multilingual Southern historian Charles Gayarré in the 1850s and 60s published a three-volume history of Louisiana covering the complex phases of its French, Spanish, and American domination. Nevertheless, I think Taylor is right to seek an “expanded cast” acting on “a broader stage,” as he wrote in the introduction to American Colonies.

But Taylor’s script for this production unfolds a violent tragedy filled with a Hobbesian grasping of power after power, a world of force and fraud, hypocrisy and delusion, racism, exploitation, and human and environmental degradation. Recently, in his essay “One Nation Divisible” (in Joshua Claybourn, ed. Our American Story: The Search for a Shared National Narrative) Taylor concluded that “There is no single unifying narrative linking past and present in America. Instead, we have enduring divisions in a nation even larger and more diverse than that of 1787. The best we can do today is to cope with our differences by seeking compromises, just as the Founders had to do, painfully and incompletely in the early Republic. Recognizing their limitations and divisions would help us deal more frankly with our own political dilemmas.”

Unless I am missing something, Taylor builds precisely a “single unifying narrative linking past and present” as potent (and distorting) as any “traditional story” attempted in the past. That narrative is oppression, hypocrisy, and white supremacy. Paradoxically, this is a unifying narrative of division. Taylor is right to say that the primary purpose of the Union of 1787 was collective survival in a hostile world of predatory empires and that political and regional compromises remained necessary to that union for decades to come. He draws in part on the work of David Hendrickson’s excellent Peace Pact and Union, Nation, or Empire. But the driving narrative is the one he began with in American Colonies. There he argued that the construction and imposition of the “white racial solidarity developed in close tandem with the expansion of liberty among male colonists” and their descendants.

In that same introduction to American Colonies, Taylor claims to have struck a balance in his narrative technique between “teleology” (presuming a known, predetermined outcome for which events serve as mere precursors) and “contingency” (“multiple and contested possibilities in a place where, and a time when, no one knew what the future would bring”). “Hindsight,” he promises, gives “a pattern” to the otherwise chaotic “change over time that readers reasonably seek from the historian.” I sympathize with this delicate operation, but the key question, then, if this role for hindsight is appropriate, is what is that thing the historian looks back on and traces to give coherence to the story? What disappears from the past when historians direct this hindsight across vast stretches of time and space to accumulate the evidence they need to convict more than to understand?

Taylor’s America of the early republic is a world almost devoid of ideas. I’m on record as calling for John Locke’s role to be deemphasized in the American Founding, but Locke vanishes from Taylor’s world altogether aside from an incidental appearance in the first volume. In American Republics there is no indication of the rich intellectual culture Americans built from the 1820s onward or the variety of institutions they propagated. Nothing about the rise of Unitarianism. No William Ellery Channing or Theodore Parker. Aside from brief mentions of Emerson, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and James Fenimore Cooper, Taylor’s America is a cultural and intellectual void. No one would ever guess from his account that there were such institutions as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, William and Mary, South Carolina, his own UVA, or the scores of denominational colleges spanning the country; or that there was sophisticated engagement, North, South, East, and West, with current European trends in philosophy, theology, history, literature, and art, and daunting theological and literary journals that routinely reviewed books in French, German, and Italian, new translations of the ancients, the works of Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe, editions of Plato, Bacon, Locke, Newton, Kant, Coleridge, Comte, Cousin, and on and on almost endlessly. And it was incredibly exciting to participate in America’s trans-regional intellectual culture. There was a palpable sense of high stakes involved in cultivating the mind and taste of a brash, awkward, young republic. Americans were making a world and not simply inflicting “cruelty, violence, and destruction” on anyone who got in their way.

But Taylor is a moral monist, and America must be judged from beginning to end by some future ideal of equality defined by the just distribution of wealth and power. For Taylor, history is still moral philosophy teaching by example.

In the last chapter of The Whig Interpretation of History, Butterfield quotes Acton again from his Inaugural Lecture: “There is a popular saying of Madame de Staël,” [Acton] writes, “That we forgive whatever we really understand. The paradox has been judiciously pruned by her descendant, the Duc de Broglie, in the words: ‘Beware of too much explaining, lest we end by too much excusing.'” Taylor’s readers are not meant to forgive. “A Whig theory of history has the practical effect,” Butterfield warns, “of curtailing the effort of historical understanding. An undefined region is left to the subjective decision of the historian, in which he shall choose not to explain, but shall merely declare that there is sin.” And sin must not escape history’s undying penalty.