James Matthew Wilson's poems in The Hanging God speak about the reality of life and the love we give, receive, or reject.

How to Leave Hatred Behind

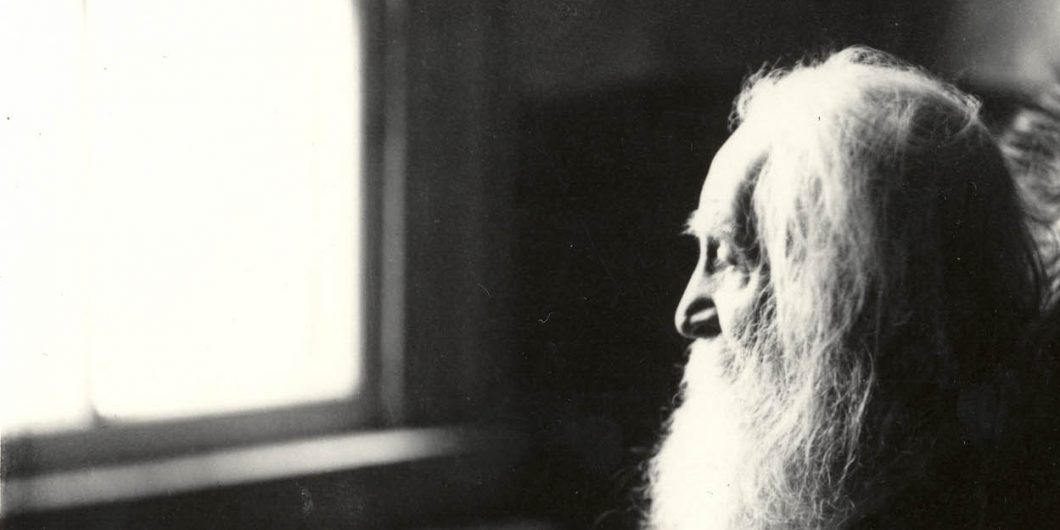

Walt and his book came out of nowhere. He was a working-class Long Islander, self-educated, and always poor. He tried various jobs, never wildly successful at anything; he wrote forgettable journalism and even worse fiction. Then, in his thirties, he self-published a slim, dark-green book on oversized paper, Leaves of Grass. After a prose preface (the first word of which is AMERICA, all-caps), the poetry begins with an astonishing untitled poem over forty pages long. The opening line startles: “I CELEBRATE myself.” It took up most of the 1855 first edition of his book and would later be called “Song of Myself.” On page after page, Whitman poured out his long free-verse lines, crammed with fast-paced montage and catalogs of sights and sounds, the human body and sex, people and cities, and the vast landscape of America. It has inspired, puzzled, and frustrated readers ever since.

Mark Edmundson’s book, Song of Ourselves, offers a clear, coherent interpretation of Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” with the full 1855 text of the poem. Edmundson argues that “Song of Myself” offers a cure for the two main threats to our republic: “hatred between Americans” and “the hunger for kings.” Whitman’s poem resists these twin evils not through political activism but by using language and the imagination to create a truly democratic soul in each of his readers. We follow the lyric speaker, a cosmic yet democratic figure named Walt Whitman (a fictionalized version of the author himself) on what Edmundson calls “an American quest.” If we experience the poem, Whitman hopes, we will recognize our deep kinship and equality with other humans, and we will reject tyranny.

Green Grass and Democracy

Against hatred and division, Whitman’s poem reveals the unity that we already have as human beings. “I CELEBRATE myself,” the poem begins, but the next two lines apply this celebration to all: “And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” Our kinship with other humans extends even to our chemistry. We’re made up of the same elements. And, since our bodies constantly take in and shed matter, and since matter cannot be destroyed, the very particles that make up our bodies are interchangeable and shared across time and space. For Whitman, this means there are no unbridgeable differences between us. If Whitman’s body has the same carbon and nitrogen and calcium as that of a president, a slave, or a prostitute (who all appear in his poem), then to hate, denigrate, or oppress other humans isn’t just contrary to good politics: it’s bad science.

Edmundson identifies the grass as the key metaphor, symbol, and model for a democratic people. Whitman writes: “A child said, What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands.” After a series of reflections, the speaker offers an interpretation that touches the heart of the American project:

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.

Grass grows among all; it does not discriminate. But more importantly for Edmundson, the grass is “a magnificent metaphor for democratic America and its people” that preserves both our individuality and our fundamental kinship with others. “No two grass blades are alike,” he writes, “Yet step back and you’ll see: the blades are all more like each other than not.”

We are all the same species, so we have shared experiences; we can also use our feelings and imagination to help us understand experiences different from our own. Whitman’s lyric speaker does this throughout his poem in some of the most dramatic passages. “I am the mashed fireman with breastbone broken,” he writes, and “Not a mutineer walks handcuffed to the jail, but I am handcuffed to him . . . Not a cholera patient lies at the last gasp, but I also lie at the last gasp.” This will change how we relate to people. Call it empathy, call it the Golden Rule: if we lovingly feel what others feel, we will treat them with dignity and respect. “In general,” Edmundson argues, “we walk the streets with a sense of isolation.” Yet if we “embrace Whitman’s trope of the grass,” then “We can look at those who pass and say not, ‘That is another.’ Instead we can say, ‘That too is me. That too I am.’” Whitman’s lyric speaker does this and calls us to do the same.

Edmundson acknowledges that for many in today’s ideological climate it has become taboo, even an act of violence, to try to understand the experiences of others, especially in artistic representation. Edmundson highlights Whitman’s magnificent lines:

I am the hounded slave . . . . I wince at the bite of the dogs,

Hell and despair are upon me . . . . crack and again crack the marksmen,

I clutch the rails of the fence . . . . my gore dribs thinned with the ooze of my skin.

Edmundson comments: “Some people now think that a White man cannot render the experience of a Black one—it is forbidden, unjust. But Walt does so, and I think he will outlast all of his detractors.” He adds, “Most slaves could not read or write. Should no one bear imaginative witness for them?” In 1855, Whitman dares to think that an African-American slave is a person like himself; and he dares to think that imagination and shared humanity might just help him understand the suffering and experience of another. And that sense of shared kinship lies at the heart of a healthy democracy.

The Tyranny of the Sun

But as the Founders warned, democracy can easily give way to tyranny, for humans seem perversely to love kings. For Edmundson, Whitman’s metaphor of the democratic grass stands in opposition to the metaphor of a tyrannical sun. “Kings and pharaohs often find their emblems in the sun,” Edmundson notes; so Whitman’s lyric speaker, who famously reclines on the grass and contains multitudes, finds an enemy in the single sun that rules on high. Whitman’s speaker describes the sunrise as a “heaved challenge from the east,” that offers a “mocking taunt, See then whether you shall be master!” He continues, “how quick the sunrise would kill me, / If I could not now and always send sunrise out of me.” Edmundson sees clearly why we sometimes crave a tyranny: the fear of chaos. In a turbulent or disordered time, we look for a strong leader to set things right. “The leader’s arrival sometimes comes as a relief,” Edmundson writes: “When the world seems to be passing out of control, we want nothing so much as stability. And sun-like men can bring it, though at a cost.”

If we believe that we are just one humble leaf among many leaves, making up the grass of our beautiful nation, then (Edmundson and Whitman hope) we can resist hatred and division.

Edmundson has given us a sensitive, affirmative work of literary criticism that resists ideology, even if the chaotic politics of the last couple of years probably shape his meditations on democracy and tyranny. Always magnanimous in outlook, Edmundson acknowledges the fruitful tension between progressivism and conservatism that has shaped our history, and some of the dangers of excess in either direction. Still, Edmundson evinces a common misunderstanding of the nature and aims of conservatism:

Taken too far, the progressive’s resistance to boundaries can lead to painful disorder, even chaos. The conservative’s affection for rules and boundaries can become suffocating.

True conservatives have no affection whatsoever for rules or for boundaries—only a love of precious things within those boundaries, and a realistic understanding of what lies without. I don’t love my backyard fence at all: I love my child and my chickens, and I rightly mistrust my neighbor’s pit bull.

Still, Edmundson astutely reads Whitman’s vision of democracy not as politically progressive or conservative but as a kind of interior spiritual state. If we believe that we are just one humble leaf among many leaves, making up the grass of our beautiful nation, then (Edmundson and Whitman hope) we can resist hatred and division. If we refuse hatred and division, then the weed of tyranny will have nowhere to grow.

Hospital Democracy

Edmundson ends his book with Whitman’s volunteer service in the Civil War hospitals. Here, he argues, the poet “became a version of the individual that his poem prophesied.” When his brother George was wounded at Fredericksburg, Whitman went to the front to find him. There he saw the grisly signs that symbolized this bloody war within the American body politic: a huge heap of amputated limbs on the ground outside a field hospital. Something happened out there in his time on the front, and before long he was in Washington, D.C. volunteering in the hospitals. It was the era before antiseptics and germ theory, and countless died from dysentery and gangrene. Many of the men were far from home, family, and friends, and Whitman worked to fill that void, visiting sometimes six to seven hundred soldiers daily. He brought them small comforts: clean clothes, ice cream, peaches, tobacco. He wrote letters for those who couldn’t. Sometimes he simply sat with them during their long labor of death. He had written in his poem, “I will not have a single person slighted or left away,” and he ministered to African-American men and Confederates in the hospitals just as he did the rest.

Edmundson writes that in the hospitals, “Whitman assumes a true humility” and teaches us what true greatness looks like in a democratic culture. “Elevated?,” Edmundson asks rhetorically, “Put on high? Tempted to think of yourself as one of the elect? Off to the hospital, the soup kitchen, the slum, the faltering school, the shelter for the victims. Walt showed the way.” Indeed, near the end of “Song of Myself,” Whitman returns to the metaphor of the grass, as we witness the lyric speaker’s death and decomposition: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,” he says, yet he goes ahead of us, hoping we will follow: “I stop some where waiting for you.” I have given what I have to give, Whitman seems to say; now it’s your turn.