The relationship of the President and his aide was one of frustration on Schlesinger’s side and irritation on Kennedy’s.

In McCarthyism’s Long Shadow

Do we need another mammoth biography of Joe McCarthy? Fervent defenses of the man and “ism,” and equally partisan denunciations, have appeared over the years, beginning almost as quickly as he rose to prominence, starting with William F. Buckley and Brent Bozell’s McCarthy and His Enemies, and Jack Anderson and Ronald May’s McCarthy: The Man, The Senator, The ‘Ism.’ He has been the subject of several critical biographies, two of which, Thomas Reeves’ The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy and David Oshinsky’s A Conspiracy So Immense, received justified praise from reviewers. A recent hagiography by Anne Coulter, Treason, and two admiring but occasionally critical accounts by Arthur Herman, Joseph McCarthy, and M. Stanton Evans, Blacklisted by History, all generated controversy. Scores of books about the Red Scare of the 1950s feature McCarthy as the central figure from Ellen Schrecker’s screed Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America to Ted Morgan’s more nuanced Reds: McCarthyism in America.

Larry Tye, author of the newly published Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy, is a journalist who has written well-received biographies of Satchell Page and Robert Kennedy. He is the first to utilize McCarthy’s personal papers, housed at Marquette University, that have heretofore been closed to researchers, and he gained access to the Senator’s medical records. He has also unearthed previously unused material from some of McCarthy’s confidants, and analyzes transcripts from executive hearings of McCarthy’s investigative Senate subcommittee that have been public for some time but have not been extensively employed. Finally, he makes use of the mountain of material about Soviet espionage that has been disgorged from American and Russian archives over the past twenty-five years and extensively discussed in a number of books (several of which I have co-authored).

The end result is an interesting, readable account of McCarthy’s “life and long shadow,” as the subtitle puts it. The new material from McCarthy’s personal archive add interesting and colorful detail to what has previously been known. Some of it redounds to McCarthy’s credit. Notably, Tye debunks claims that McCarthy vastly overstated his wartime record for political gain. He documents his considerable personal charm and the very real medical issues that contributed to the addiction to alcohol that eventually killed him.

An “-ism” Larger than the Man

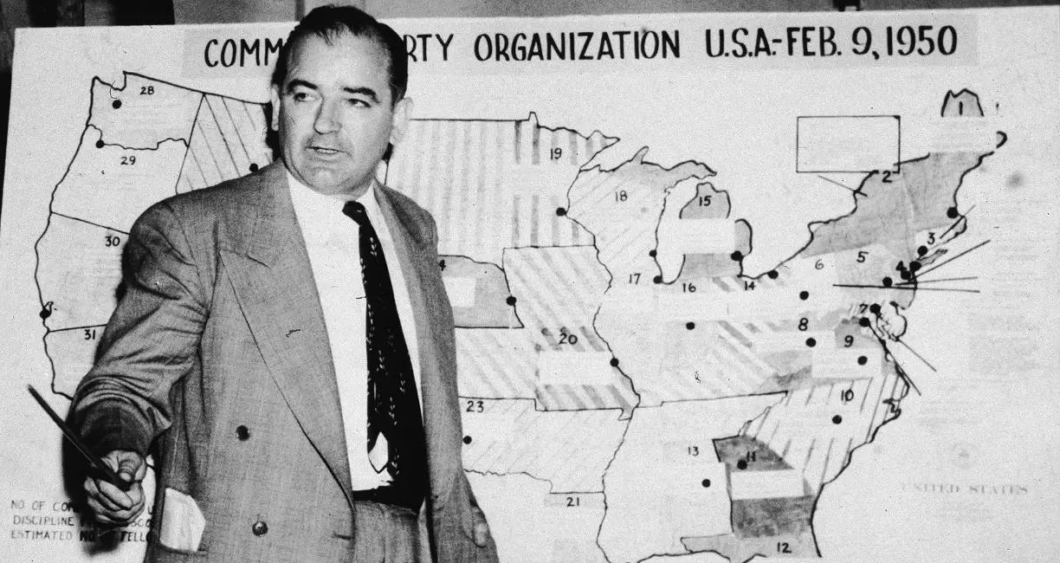

McCarthy has assumed a remarkably prominent role in American history. As Tye notes, standard American history textbooks mention McCarthy and McCarthyism more frequently than most presidents. How did a United States Senator, elected in 1946, unknown to most Americans and dismissed as late as January 1950 by most of his colleagues as an intellectual and political lightweight, become so prominent? His period in the national spotlight lasted less than five years, from his speech charging that the State Department was riddled with Communists in February 1950, until his denunciation by the Senate in December 1954. He died in May 1957, only forty-eight years old, shunned and ignored by most of the press, politicians, and public that had previously hung on his every word.

While McCarthy often dominated the headlines in that five-year period with his claims that the American government was riddled with communists, he actually unearthed relatively few spies. For the first three years after he burst into the news, as a member of the Senate minority, he could not launch any investigations into the charges he made. He made headlines as he hurled charges and enraged Democratic senators and the Truman Administration supervised a futile effort to discredit him. He chaired a Senate investigative subcommittee for less than two years, the only period during which he was able to order hearings, subpoena witnesses, and actually pursue his claims.

His name is now attached to a political phenomenon, McCarthyism, that virtually everyone uses as an epithet. It suggests wild, unsupported charges and claims directed against individuals, and is now deployed by partisans of every variety to excoriate their critics. McCarthy failed to distinguish between spies, Communists, ex-Communists, communist sympathizers and liberal anti-communists. His most risible charge was that General George Marshall, Chief of Staff during World War II, and former Secretary of State and Defense and, was part of “a conspiracy so immense” that it dwarfed any heretofore seen in history. But, he also pilloried government officials who had joined communist front groups naively or for misplaced enthusiasm for the Soviet Union when it was seen as a bulwark of anti-fascism.

McCarthy’s scattershot approach to identifying communists even led him to miss genuine Soviet spies. One of the cooperative witnesses before his committee, Nathan Sussman, had been, we now know, a member of the Rosenberg spy ring. Neither McCarthy nor his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, even questioned Sussman about his ties to Julius Rosenberg, allowing him to pretend to pose as a disillusioned ex-Communist. As Tye notes, even some conservatives with impeccable anti-communist credentials, ranging from Whittaker Chambers to Frederick Woltman and Herbert Philbrick warned that McCarthy was harming the anti-communist cause he professed to be serving with his wild charges, sloppy investigative work, and innuendos.

The Reality of Soviet Espionage

But Tye sometimes lets McCarthy’s targets off the hook too easily. He first accused Owen Lattimore, a sometime State Department consultant and influential commentator of Far Eastern affairs, of being the top Soviet spy in America. When the Senator realized that claim was ludicrous, he charged Lattimore with being a conscious tool of the Communist Party and a major architect of American policy in the Far East. At McCarthy’s instigation, Louis Budenz, an ex-communist, suddenly recalled being told by high-ranking CPUSA officials about Lattimore’s importance, even though he had never mentioned his name to the FBI during years of briefings. While Tye justifiably excoriates McCarthy, he gingerly skates over Lattimore’s long record as a Stalinist fanboy, and his assistance to avowed communists in and out of the government.

As the Venona messages that were being decrypted by the government even as McCarthy was riding high—but not being shared with the public—made clear, several hundred Americans had cooperated with Soviet intelligence and only about a third of them were ever identified.

Similarly, the Tydings Committee, created by the Senate to investigate McCarthy’s initial charges against the State Department, conducted a flawed investigation marred by partisan loyalties. John Stewart Service, a China Hand arrested in 1945 during the Amerasia spy case, was never indicted. Service had not been a spy, but he had leaked information designed to undercut American support for the Chinese Nationalist government to Amerasia’s editor, who was, unbeknownst to Service, trying to set up a spy ring. Sympathetic high-ranking officials in the State and Justice Departments had connived to protect Service—one of the prosecutors deliberately went easy on him before the grand jury—and the Associate Attorney General at the time later committed perjury when he was confirmed by the Senate as Attorney General of the United States (he denied interceding in Service’s case, even though the FBI had a wiretap of him helping to fix the case). Including that context would have helped Tye to explain why many conservatives and Republicans gave some credence to McCarthy’s claims—even when they were wrong.

Tye does mention the moral ambiguity that made the Red Scare so problematic. McCarthy, he notes, was “not always wrong,” and “the more we learn, the fewer heroes this story has.” Unfortunately, he sometimes allows his wholly justifiable disgust with McCarthy and his tactics to obscure the lies, feigned outrage and moral posturing of some of his victims. The archival revelations of the past twenty-five years have demonstrated that while McCarthy was wrong about many, if not most, of the individuals he attacked, he was right about the massive extent of Soviet espionage that had taken place in the United States. More than 500 Americans had cooperated in one way or another with Soviet intelligence in the 1930s and 1940s, including several high-ranking government officials.

The Legitimacy of Anti-Communism

While Tye admits that McCarthy’s charges about communists and communism had a basis in fact, he is unduly critical of efforts by the Truman Administration to deal with the issue of communists in government through the loyalty-security program, complaining that the investigations were “based on beliefs rather than actions” and “defied basic American principles of justice.” And, while he recognizes the subordination of the Communist Party of the United States to Moscow and the security issues created by communists serving in sensitive government positions, he fails to suggest how the government could or should prevent people belonging to a political movement opposed to American democracy from occupying government positions, criticizing Eisenhower for not challenging McCarthy’s premises that “merely believing in communism was dangerous, and that Soviet subversion threatened the stability and safety of America.”

That omission occasionally leads to an off-putting remark, like branding Whittaker Chambers, “the most famous of the anti-Communist tattletales.” But, the hunt for people in government with communist ties was not a child’s game. Chambers, by exposing Alger Hiss and Larry Duggan, former high-ranking State Department officials, and Harry Dexter White, once the number two man at the Treasury Department, as communist agents may have launched the Red Scare, but he performed a necessary public service.

As the Venona messages that were being decrypted by the government even as McCarthy was riding high—but not being shared with the public—made clear, several hundred Americans had cooperated with Soviet intelligence and only about a third of them were ever identified. No doubt the Loyalty-Security program had flaws and sometimes led to unjust results. But the overwhelming majority of Americans who had cooperated with Soviet intelligence were communists and communist sympathizers. Removing them from positions of responsibility was vital.

Exaggeration and Its Consequences

My other concern with Tye’s otherwise impressive book is that he vastly exaggerates both McCarthy’s reach and its consequences, insisting that at the height of the Cold War “meaningful dissent had been all but eliminated,” and that movements for world peace, women’s rights, workplace safety, civil rights, and universal health care had all been “set back a decade of more” by McCarthyism.

McCarthy intimidated and damaged many people. His attacks may have contributed to several suicides, ruined some careers and led some people to avoid controversial topics and issues. But he never lacked prominent critics, including individuals, institutions, or newspapers who challenged, denounced and defied him. While Tye complains that organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union or the CIO failed to oppose him vigorously enough, he does not adequately account for the fact that their own experience with communist infiltration over the years meant that to be true to their own values they had to oppose both McCarthy and the communists. By the same token, calling President Eisenhower McCarthy’s “enabler-in-chief,” is too harsh. Did Ike sometimes fail to exhibit political courage in his confrontations with the Senator? Surely, he did. But, he also slowly—perhaps too slowly—but surely put together a coalition within the Republican Party that ended McCarthy’s career.

McCarthy was an opportunist politician who glommed onto an issue that frightened the American public. His sudden ascent was, in part, owed to missteps by the Truman Administration which initially downplayed the extent of Soviet subversion. From the President’s own characterization of the Hiss Case as a “red herring,” to Secretary of State Acheson’s comment after his conviction that he would not turn his back on Alger Hiss, many Americans gained the impression that the Administration did not take the issue seriously enough. That Truman also reversed FDR’s willingness to tolerate cooperation with communist and pro-communist forces, culminating in the ouster of Henry Wallace and his allies in 1948, began an effort to weed communists out of the government, built NATO, resisted communist aggression in Korea—all before McCarthy’s rise—is compelling evidence that whatever its errors or missteps, liberal anti-communism got it mostly right.