By pushing more government-sponsored loans, Fannie and Freddie are feeding the already runaway house price inflation.

Inside the Housing Hot Zone

Max Holleran’s new book, Yes to the City, chronicles a hot front in the culture war. The battle rages through every city in the land. The outcome will shape America’s future more than inflation, covid, or the war in Ukraine.

I speak, of course, of zoning codes.

You seem unconvinced. Yet city planning touches every part of our lives, and there is a rich, albeit neglected, conservative literature on the topic. Obdurate towns, hoping to shield themselves from change, have built regulatory mazes that serve as potent weapons in the hands of any canny culture warrior. The result: fissures in American society between young and old, rich and poor, Right and Left.

In January 2020, Guiding Star Wakota, a crisis pregnancy center serving moms in the independent city of West Saint Paul, Minnesota, sought to expand its overcrowded facilities. It wrote up exhaustive plans for how the project would meet each rule of my hometown’s sprawling zoning code, and requested only one small variance: an exception to its parking minimums. West Saint Paul’s code required Wakota to have 37 parking stalls. Everyone knew the requirement was absurd for this lightly-trafficked facility, and variances were granted as a matter of course to projects of all kinds. (The city cut the requirement by half zonewide barely a year later.) Wakota reasonably expected smooth sailing when they sought approval with only 29 stalls.

Instead, dozens of locals, who opposed Wakota’s mission, persuaded the commission to reject the plan. Wakota desperately struck a parking deal with a neighbor, withdrew its request for a variance, and, backed by hundreds of locals, appealed to the City Council. City Council members did all they could to block it, but, faced with the threat of a lawsuit they would lose, they chose acquiescence.

In the shadow of the zoning codes, very little commercial and residential development in American cities can be called “free” at all.

Yet it all hinged on Wakota making that lucky, last-minute parking deal. If they had not, the City Council majority would certainly have denied the variance, and the moms Wakota serves would be out of luck. Naturally, the Council would have rubber-stamped the variance for anyone else. They just hate crisis pregnancy centers.

As I dug deeper into city planning, I learned this is totally normal. By combining restrictive zoning codes with copious variances and conditional use permits (granted at a city’s discretion), 21st-century cities across America have given themselves sweeping power to decide exactly what gets built, where, and by whom. In the shadow of the zoning codes, very little commercial and residential development in American cities can be called “free” at all.

Unsurprisingly, this degree of central control causes problems, and not just for pro-life charities. The housing market has gone from “red-hot” to “actual crisis” in much of the country. Rents and home prices are through the roof, especially near city centers where good jobs are. Many of my fellow Millennials are unable to move into the kind of homes our parents bought when they were our age, with ominous long-term effects on family formation and household stability. There simply aren’t enough housing units. Zoning mandates for low-density housing have prevented cities and inner-ring suburbs from increasing density, despite growing populations. Over half my city is zoned for single-family homes only, on lots no smaller than 7,000 sq. feet. No townhomes, row houses, or pop tops allowed, and, oh yes, our land is full. This is typical.

Yes to the City: Millennials and the Fight for Affordable Housing is an exploration of this crisis and my fellow Millennials’ attempts to fight back through the YIMBY movement. YIMBYism (short for “Yes In My Backyard”) is a reaction against NIMBYism (“Not In My Backyard”). NIMBYs support America’s restrictive land-use laws and their aggressive application. Those laws arose for often-understandable reasons: typical NIMBYs are longtime residents of a neighborhood who don’t want their beloved home to become dangerous, devalued, or distasteful. Yet, too often, their rules strangle the natural growth and development every city needs to thrive.

YIMBYs want to build denser, mixed-use housing, bulldozing regulations that get in their way. Although “YIMBY” isn’t new, Holleran dates the start of the YIMBY political movement to 2014. The Silicon Valley boom had brought a large new population to San Francisco, putting extreme pressure on housing prices. Then came the backlash. New renters formed the Bay Area Renters Federation (or “BARF,” because too-cute Millennial irony peaked in the 2010s). They made YIMBY their creed, and their movement grew faster than 1950s urban sprawl.

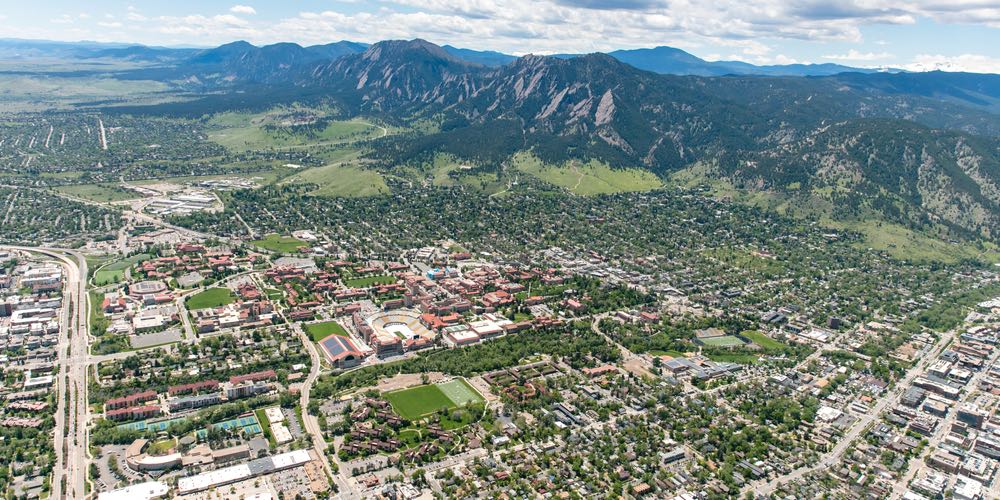

Yes to the City is structured as a series of investigations into five different conflicts the YIMBY movement has dealt with as it grows: YIMBYs versus anti-gentrification activists, YIMBYs versus Baby Boomers, YIMBYs versus environmentalists, YIMBYs versus “urban authenticity,” and YIMBYs versus The Rest of the Planet. Holleran relates each conflict to a specific city in order to bring it to life: San Francisco, Boulder, Austin, and Melbourne. (Yes, that’s only four cities. Chapter Two, about Boomer NIMBYs, inexplicably drops the city gimmick.)

To his credit, Holleran never flirts with hagiography. He gives a fair hearing to the YIMBYs’ opposition, especially opposition from the Left. We learn that anti-gentrification activists dislike YIMBYs because new development tends to happen in poor neighborhoods. That causes gentrification, which means poor people lose their homes. Activists want YIMBYs to stick to wealthy neighborhoods, while YIMBYs want to build high-density housing on cheap land. Thus, there is conflict. Environmentalists often oppose YIMBYs, too, because YIMBYs are desperate for places to build apartment blocks, and government-owned green space can look awfully attractive. In describing these conflicts, it’s not even clear which side Prof. Holleran is on.

Holleran is equally unsparing toward the YIMBYs themselves. He paints them as obnoxious out-of-towners who shout in meetings before going home to passive-aggressively meme (quite badly) online. One representative YIMBY in the book proclaims, “Fuck local control,” while the founder of the movement chimes in with, “nobody gives a shit what color you think someone else’s shutters should be.” They are renters and apparently plan to stay that way. Thus, they claim no allegiance to any particular town, and they show little interest in “densification” when it comes to owner-occupied property like, say, starter homes.

Startlingly, Holleran reports, “not a single [YIMBY] interviewed did not have a university education.” YIMBYs don’t bother building mass popular support because “they are far more interested in finding expert-driven solutions.” Which experts? Turns out, themselves! “Because so many millennial YIMBY activists have training in architecture, design, and urban planning, the local government’s rebuffing was particularly irksome, because it went against professional consensus and threatened their position both as renters and as members of a knowledge field.” Rarely does an author so castigate his subjects!

Yet, at times, one sympathizes with Holleran’s YIMBYs. Although their rootlessness makes them avatars of the atomizing, corrosive ideology conservatives have come to call “liquid modernity,” they might as easily be seen as its victims. Sent out into naked modernity by an upper-middle-class success script, sacrificing close community ties to make their way in a distant city, these kids find the price—both figurative and literal—far higher than they can afford. One anonymous YIMBY told Holleran, “A person has the right to live in the community that they want to live in.” I doubt it’s accurate to call this a “right,” but certainly America thrives when people can choose where they live. Desperate migrants, fleeing everything from Jim Crow to Irish potato famines, have been one of the most important drivers of America’s eternal renewal. That dynamism dies if the migrants have nowhere to live at the end of the rainbow.

If this book is any indication, even conservatives eager to make common cause with the YIMBYs will struggle to be accepted.

The power to choose where one lives also benefits the lifelong local who treasures his community ties and wants to buy a house in his own neighborhood. On the block where I grew up, inflation-adjusted house prices have roughly doubled since 1990, with the sharpest hikes coming over the past five years. I, on a software engineer’s generous salary, found in the late 2010s that I could not afford to move into the modest Twin Cities neighborhood that my philosophy professor parents, living in self-proclaimed “genteel poverty,” had moved into in 1991. It’s hard to imagine what it’s like for kids who grew up in San Francisco or Austin, where, since 1990, home prices have tripled. (Again, that’s after counting inflation.)

YIMBYs are trying to fix this. Hooray for YIMBYs! Indeed, YIMBYs are trying to fix it by railing against restrictive government codes and overweening oversight, by fighting powerful interest groups and their sweetheart regulations, and, ultimately, by demanding that the invisible hand be unshackled at last. With that résumé, you’d expect YIMBYs to be writing for Law & Liberty!

Sadly, it seems that conservatives (especially dread libertarians) are the villains of the YIMBY movement in general, and this book in particular. Holleran is at pains to separate the YIMBY movement from developers, libertarians, and markets. Far-left housing activists frequently lambaste the YIMBY movement as a catspaw for market liberalism and deregulation. Rather than replying that markets and deregulation are powerful tools that even progressives ought to harness, Holleran’s YIMBYs evade the charge by gesturing vaguely toward affordable housing mandates that hard-left critics decry as ineffective (correctly, as far as I can tell from Yes to the City). If this book is any indication, even conservatives eager to make common cause with the YIMBYs will struggle to be accepted.

Holleran tells this entire story in a vague, view-from-nowhere voice. His history of the titular “Fight for Affordable Housing” avoids exciting civic drama like the Wakota incident. It also avoids deep, careful data analysis. Instead, much of the book consists of sweeping, faceless claims like, “YIMBYs argue that…” “YIMBY activists push back [that]…” “Many anti-gentrification activists say…” and “For YIMBYs….” Actually, I got all four of those from the first two paragraphs of page 107, a page I opened at random. None of those claims are graced by a name or even a citation. It’s often impossible to know whether the author is accurately describing the movement’s views, or his own. The whole book feels like a novel written entirely in the passive voice.

When Yes to the City does offer citations, it does not always slake the reader’s thirst for evidence, or even just detail. There are 455 endnotes, but they are often broader than the Maginot Line and about as useful. For example, Holleran claimed that “some urbanists… mainly supported the [Boulder] greenbelt as an urban planning measure that gave authority back to city technocrats.” Intriguing! I wanted to know more. Holleran’s endnote for this reads, in toto: “Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring.” Look, I don’t need much from endnotes. I don’t care where the book was published. But I do need a page number, and Holleran lists none. Forcing the Spring is 484 pages long. It is not about Boulder. It does not contain the word “greenbelt.” Yes to the City did little to allay my suspicion that authors who use endnotes over footnotes are trying to hide something.

Meanwhile, Holleran seemed willing to grant anonymity to anyone who asked, no matter how anodyne. Claims by identifiable sources make up a relatively small part of the text. This is a shame, because the named interviewees help ground the book in real life. Holleran’s oral history of Boulder’s “greenbelt” (a ring of government-owned land around Boulder that blocks sprawl) is the best part of the book, mainly because it introduces us to characters like math professor Bob McKelvey. This man set a boundary for development in Boulder by walking up to a poster board in 1958 and arbitrarily “drawing the line as low as I could draw it.” Boulder’s “Blue Line” remains a basis for regulation today. Fascinating! Alas, we’re soon back to prose like this:

NIMBYisitic objections are often well founded… Concern about one’s backyard is often a deeply deliberative form of community engagement that addresses the carrying capacity of land with on-the-ground knowledge that is attuned to environmental quality and social cohesion. However, it can become a mindset that denies all changes made at scale, embracing some of the more pernicious aspects of American federalism and home rule. Preserving independent, devolved decision making can come from overall skepticism about ‘big government’, but also from latent racism or an unwillingness to share space and resources with others.

Holleran means that NIMBYs know a lot of useful things about their hometowns, but a lot of them hate change, because some NIMBYs are conservatives, some are selfish, and some are racists. A writer may choose to say a short thing protractedly in order to clarify a point, or for beauty’s sake, but this is twaddle.

Yes to the City: Millennials and the Fight for Affordable Housing is not a good book. From its shaky overall architecture to its wormy prose foundations, it struggles to make its points clearly or persuasively. Nevertheless, the Yes In My Backyard movement Holleran depicts is playing a critical role in the growing culture war over city planning. Conservatives interested in strong communities, the common good, and small government would do well to study and learn from the YIMBY movement. If nothing else, we might get a better book out of it.