That is not to say the judiciary has no role in constitutional interpretation, only that it is part of the ongoing conversation that comprises republican p

Investigating Madison's Political Religion

In the preface of James Madison and Constitutional Imperfection, Jeremy D. Bailey mentions in an aside that he will not speak of Madison’s theory of religious liberty; yet the entire text that follows is taken up with a discussion of Madison’s religion.

I do not mean that Bailey scours Madison’s corpus for evidence of Christian faith or that he seeks, to the contrary, to prove once and for all that the Founders were religious skeptics. He makes no inquiry of the sort. Rather, he investigates what I consider Madison’s political religion. He points, using Madison’s language, to the U.S. Constitution as “holy writ” whose defenders need “holy zeal” to defend it. Likewise the broader American public ought to feel “veneration” for the “miracle” that the Founders wrote the writ. In short, the idea here is that James Madison transposed the Protestant fervor for the Word onto a republican dedication to the Constitution.

The movement from divine to human writ brings with it the imperfection to which the book’s title alludes. Founders and citizens are all imperfect, and the document that the Founders produced and the citizens ratified bore that imperfection. For Bailey’s Madison, the republican sins of the Constitution were twofold. The specific sin was the compromise on state equality in the Senate, and it flowed from the more original sin: the inability to revise the holy writ when necessary because of the very zeal to preserve it.

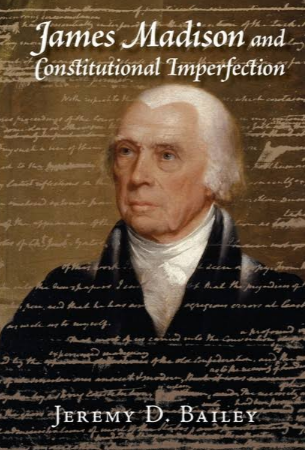

As Bailey capably reveals, James Madison (1751-1836) labored over these questions his entire life. Hence, the cover greets the reader with Chester Harding’s 1829 portrait of an old, tired, yet clear-eyed Madison. Superimposed is a reproduction of the letter that Madison wrote to John G. Jackson on December 27, 1821, in which he explains his efforts to write the history of the 1787 Convention. The cover communicates to the reader that the true Madison is the older Madison, whose ideas matured with the young republic he helped to found.

Bailey is the Ross M. Lence Distinguished Teaching Chair for both the Department of Political Science and Honors College at the University of Houston. (Full disclosure: I am an alumnus of that institution, majored in Political Science, graduated a member of its Honors College, and took four courses from the late Ross M. Lence.) The author’s earlier research focused on the executive power and, in particular, Thomas Jefferson’s view of it. His work on Jefferson clearly informs his work on Madison.

This book is framed as an effort to move beyond “Madisonian constitutionalism” as the proper interpretation of Madison’s political philosophy. What is the need for this departure? The term “Madisonian constitutionalism” comes from scholars who, in Bailey’s view, take too confined a view of Madison’s work. These scholars too often elevate what he wrote from the Constitutional Convention through ratification over what he wrote in the interval between the first Congress and Jefferson’s 1800 election, and especially over what the former Congressman, Secretary of State, and President wrote during his retirement. Others have tended to treat Madison comparatively, defining him only by his points of departure from Alexander Hamilton or Thomas Jefferson.

Bailey takes broader view chronologically but a focused view on the ways in which Madison “spent the vast majority of his life helping Jefferson . . . [and] inevitably made the United States and its Constitution more Jeffersonian.” In so doing, he corrects the “frequently too narrow” efforts to provide “a representative sample of Madison’s career.” The author’s focus is not, however, too narrow for him to consider how Madison debated with Jefferson, Washington, Adams, and later Martin Van Buren. Rather, these debates are examined so as to make the Madisonian position emerge more clearly on its own terms.

The central claim is this: Madison was more or less a Jeffersonian, especially after ratification, but his Jeffersonianism was more moderate than Jefferson. Through eight chapters on subjects such as veneration and popular opinion, Bailey pores over Madison’s later papers to bring out the subtleties of where he differed with Jefferson and where he didn’t. He makes an interesting distinction: that Madison differed with Jefferson about the rationale behind placing greater trust in popular opinion, but not about whether one should put great trust in popular opinion to remedy constitutional imperfections.

Unsurprisingly, the most essential objection for Bailey to overcome—and he places it at the center of the text—is the one that any student of the Federalist Papers would make. Doesn’t Madison, in Federalist 49, directly contradict the Jeffersonian position? In other words, didn’t Madison reject a revolutionary approach in favor of encouraging veneration of the founding charter? The traditional “Madisonian constitutionalist” position pits Madison’s thoughts on veneration against what Bailey describes as Jefferson’s “revolutionary politics of founding . . . [as a] way to purify and elevate the otherwise corrupted opinions of the majority.” Bailey does not want the story to end there. Instead, he answers with a close reading of the arguments Madison makes throughout his 26 contributions to the Federalist Papers about the relative importance of appealing to the people for constitutional change.

As with any interpretation, Bailey has to rely on stressing some of Madison’s claims over others. To the traditional Madisonian constitutionalist’s adducing of Federalist 49, Bailey answers by adducing Federalist 37.

In Federalist 37, Madison compares the Bible to the Constitution. The problem with the two is the same: its use of language, for even when “the Almighty himself condescends to address mankind . . . his meaning, luminous as it must be, is rendered dim and doubtful, by the cloudy medium through which it is communicated.” Worse for the Constitution is its human authorship, which lacks such luminosity but retains the three issues of language Madison raises: “indistinctness of the object, imperfection of the organ of conception, [and] inadequateness of the vehicle of ideas.”

Perhaps to compensate for what Bailey calls Madison’s “impiety,” Madison then credits the success of the 1787 Convention not to the Constitution but to the laying on of “a finger of that Almighty hand which has so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution.” Yet Madison, as Bailey argues throughout, does not recommend remedying constitutional imperfection by pleading for a divine hand. On the contrary, Madison, like Jefferson, appeals to the people.

For Bailey, the imperfection argument in Federalist 37 trumps the veneration argument in Federalist 49. This means that the people should only venerate what is perfect in the Constitution and seek to improve its imperfections. Therefore one could say that Madison voted for Jefferson before he voted against him, only for Madison to veer back to Jefferson after ratification.

Bailey presses his case for Federalist 37 as central for the later Madison. He looks at the favorable turn to popular opinion during the years between the 1788 ratification until Jefferson’s election in 1800. One example comes during the bank controversy of 1790: By then, Madison had embraced partisanship and had elevated the party of Jefferson as “the party of public opinion.” Public opinion, for Bailey’s Madison, was the true sovereign, and public opinion could be either “fixed” or “unfixed.” Interpreting Madison, Bailey says:

When public opinion is fixed, it must be obeyed; but where it remains unfixed, there it can be influenced by the government. This distinction, Madison argued, “would prevent or decide many debates on the respect due from the government to the sentiments of the people.”

Fixed opinion took time to form, and in this regard Bailey cites Madison’s observation that “a bill of rights . . . acquires efficacy as time sanctifies it and incorporates it with the public sentiment.” The Constitution’s Bill of Rights, now “sanctified,” has become holy writ for the public at large. Yet vast spaces for public debate remained in place for government to influence what the public may yet hold sacred in the future.

The people preserved government with fixed opinions about its nature, and government sought to reform the people by influencing their unfixed opinions. Consequently, Bailey is reinterpreting Madison as falling far short of the traditional view, which has him demanding zeal and veneration of the Constitution. He says, rather, that Madison thought of the American Constitution as “so complicated that it required more veneration than usual.”

This interpretation seems to me creatively Madisonian because it achieves not so much a resolution but balance between two competing forces. Fixed public opinion about the Constitution required veneration, but unfixed opinion allowed room for remedying constitutional imperfection. We can see that even Madison’s “holy zeal” was moderate, because a zeal for the Constitution also encountered contravening passions, such as self-love, that resulted in an “equipoise of the passions” replicating, on the personal scale, what the extended republic of Federalist 10 was on the national scale.

Bailey’s reliance on 37 over 49 is the critical choice and the major contribution he makes to the study of Madison and the Founding. This slim volume (under 200 pages) is dense with extended textual interpretation of Madison’s later writings that verify Madison’s embrace of Jeffersonian politics and, with it, a distancing from veneration in favor of appealing to public opinion. Thus does Bailey accomplish one of the high ends of academic scholarship: challenging the current consensus with a unique position and dedicated archival work intended to reach closer to the truth about his subject. One is tempted to say that Bailey regards contemporary veneration of Madisonian constitutionalism as imperfect and in need of an appeal from the people of the Founding to render their judgment.

In a text dense with argumentation and evidence, the quality of the prose can suffer. Bailey’s is very serviceable but uneven, in places relying on numerical lists of reasons for the claims offered. These lists, scattered across the book, read like outlines shorn of their form. Even so, the book has more than its originality to recommend it. Each chapter begins with an excellent overview of the current state of Madison scholarship, and these introductions would be valuable refreshers even for active scholars in the field.

All in all, James Madison and Constitutional Imperfection would be well suited to an upper-level undergraduate or graduate course on the Constitution or American Political Thought. Students interested in Madison could easily make use of Bailey’s references and summaries to learn the contours of the debates over this crucial figure.

As someone deeply invested in the quality of Ross Lence’s successor, I am happy to see Jeremy Bailey produce innovative and thorough scholarship. I’m tempted, of course, to wonder what the Reasonable Mr. Lence would have thought. In my mind’s eye I see him demanding that Bailey invest in a sturdy pair of suspenders and, with a twinkle in his eye, pondering whether calling Madison a “Jeffersonian” was an insult.