Acolyte of Ambition: Balzac’s Lost Illusions and Lost Souls

“You can learn a lot from Mr. B,” Bob Dylan wrote of Balzac. “His philosophy is plain and simple, says basically that pure materialism is a recipe for madness. He wears a monk’s robe and drinks endless cups of coffee,” writing his Human Comedy through the silent night. This recorder of modernity is akin to a medieval illuminator whose quills can cull the sublime from the shabby. His Lost Illusions, freshly translated by Raymond MacKenzie, should be required reading for every peddler of the pen, and everyone stricken by the climber’s desires. For, with homeopathic skill, Balzac cures the soul-sick through artful administrations of what ails us.

The protagonist Lucien, self-styled poet, fails to find recognition in provincial Angoulême, where the arts are “roundly deplored.” Ready to “avenge the humbleness” of his origins, Lucien leaves home armed with grand visions and—a poetry collection. Maybe Paris, that antithesis of country pettiness, can do justice to the young man’s genius.

When, mocked by publishers, his pretentions are proofread into oblivion, he briefly swaps his strivings for friendship with “the Cenacle,” a brotherhood of truly talented artists and totally committed philosophers. Led by Daniel d’Arthez all of them “had that slightly tormented look that a pure life and a fiery mind give to the face, regularizing it and purifying it.” This little flowering of resolve blooms fast and dies. Having spent his last monies on firewood, Lucien again borrows from his homespun family. Filching egoism’s fluid currency with the confidence of a bank too big to fail, he subjects them to the vicissitudes of “self-made” fate.

Again short on cash soon thereafter, the poet descends into dubious journalism. Lucien’s infernal turn coincides with another counterfeit of the good. He cohabitates with Coralie, a gorgeous actress whose theater manager purchases canned applause, manufacturing high ratings for her mediocre performances. Balzac’s observations on journalism are pessimistic but penetrating; although “news” was in its infancy, he is keen to its fundamental causes and its frightening sovereignty. Claude Vignon, a prolific article-maker and colleague of Lucien, anticipates Nietzsche’s observation that the newspaper will replace prayer—the ephemeral will eclipse the eternal. The newspaper, surpassing the “role of the priest,” can “make its readers believe anything it wants to. Then nothing it dislikes” can possibly be correct, “and it is never wrong.” A paper—the people “in folio form”—“will serve up its own father raw, or seasoned only with the salt of its witticisms, rather than fail to entertain or amuse its public.” Filled with pithy, painful truths, Vignon’s diatribe is that of an addict against his narcotic.

Before long, Lucien is “depraved from the habit of writing both for and against.” When different bosses task him with celebrating and decimating the same book, he learns that the newspaper “like the magic spear of Achilles . . . heals the wounds it inflicts.”

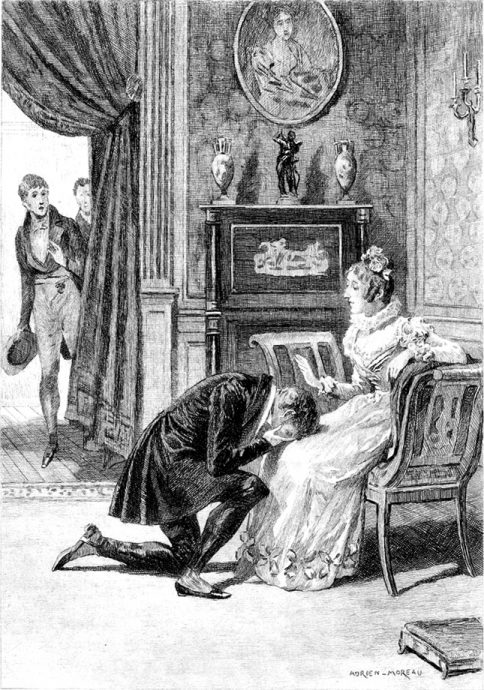

Then the Liberal Lucien enters journalism’s red light district, whoring himself to the Royalist papers in anticipation of their likely ascent. Instead, a convoluted tit for tat blackmail awaits. If he does not wish to watch his Coralie paraded through public scorn, he must excoriate a newly-published book by d’Arthez, the soul of the Cenacle. Like a discreet Judas, Lucien pays d’Arthez a nocturnal visit. Penitent before his hallowed friend, Lucien betrays him with a kiss: “Your book is sublime!” he professes, then confesses to having written a damning review. In one of the most potent reverses in a novel replete with twists and turns, the betrayed d’Arthez helps draft his own death sentence. By perfecting the document that will sink his genius, d’Arthez translates St. Paul’s harrowing wisdom into the idiom of editing: “Therefore if thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink: in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head” (Romans 12:20). D’Arthez then weighs the poet’s transgression in the scales of transcendence:

I’ve always regarded periodic repentance as a great hypocrisy . . . Repentance becomes just the price you pay for permission to commit your wicket acts. But repentance is a kind of virginity that our soul owes to God: a man who repents twice is a disgusting sycophant. I fear that the only reason you repent is to get your absolution!

Would that this prophecy remained unfulfilled. For although “from that day on [Lucien] felt devoured by a melancholy that he could not always disguise,” he knows no real remorse. Balzac takes pains to make this plain.

Before he is barred from both journalism and socialite stardom, Lucien drives Coralie to an early death. Exhausted, she takes to bed after receiving “legitimate applause, a response that had not been paid for.” The spontaneity and sincerity of the crowd’s appreciation helps her turn from falsified triumphs. While Coralie lays dying, Balzac hypostasizes the shabby and the sublime. Lucien composes bawdy drinking songs to raise funds for the funeral. The priest proclaims a solemn beatitude that, though meant to bless, comes off as comfortless: “Happy are those who find their Hell here on earth.” Sustaining a Catholic coloration shameful to Lucien, Balzac paints the poet’s last stance in Paris with an allusion alien to the irreligious striver. After begging alms from Coralie’s caretaker, he pines to give the money back, for it “burned in his hand . . . but he was forced to keep it, a final stigmata from Parisian life.”

Overcome with illness on his way home, Lucien receives absolution from an unassuming priest who does not know that “for the past eighteen months Lucien had repented so often that his repentance now, violent as it was, had no more value than a well-acted scene—and one that every time had been acted in perfect good faith.” The counterpoint to Coralie is clear: whereas the actress, in her death throes, retired from acting, Lucien’s living confessions are semblances—the usurious interest of his illusory existence.

The stigmata, nailed into his hands by the city’s burning monies, persists even after the prodigal receives a manmade resurrection. Back in Angoulême he appears at first chastened, relieved to be far from the mutable feast of big city achievements. But his perilous desires are soon petted and purring. At a soirée held in his honor, his hauteur reaches liturgical proportions. When a lawyer calls him a “man of genius,” Lucien “made the kind of gesture you might see in church from a man who finds the censer too close to his nose.” Six days after his triumphant return, he yearns for the “wonderful miseries” of Paris. When Angoulême ultimately fails to appreciate him, Lucien serves up a favorite entrée of bohemian “great men”: “They’re all bourgeois; they can’t understand me.” Balzac, calling his bluff, discloses his recipe’s main ingredient: “he could no longer fool them about his character or his future.”

Cornered by his failures and their consequences for his family, he takes refuge in fate, that category of inevitability that absolves ethical responsibility: “Many families have a member who is fatal for them, like a kind of illness or infection. That is what I am for you,” he writes his sister, promising suicide in recompense.

Ready to off himself, Lucien contemplates ways to die “poetically,” eschewing the hideous spectacle of his dead corpse fished from the river. Flowers in his hands, imagining a beautiful death, Lucien is interrupted by a man who seems—“obviously”—to be a priest, but who is actually the serial criminal Vautrin, a central presence in several Balzac novels. With charm and lure that reads as all-too-plausible, the Jesuitical “Father Herrera” tempts Lucien away from the edge by remarking repeatedly upon the young man’s beauty and oiling the over-worn engine of ambition.

Balzac does not hesitate to tell us what to think. Early in Lost Illusions, for instance, after painting a portrait of rurality, he tells us that “the most ridiculous things about us are born out of fine sentiments, by virtues or abilities carried to an extreme. A pride that is never smoothed down by contact with society ends up becoming a rigidity that exercises itself on trivialities.”

The scene carries a “supernatural” sense. So says MacKenzie in his translator’s introduction. According to the strictures of literary realism, Father Herrera’s sudden arrival seriously tests our suspended disbelief. How, then, could we justify this turn? “Is it Providence, working to keep Lucien from his intended suicide, or the opposite, a Satanic kind of intervention?” Herrera, notes MacKenzie (and his extensive notes are extraordinarily helpful), seems more akin to the demonic Mephistopheles of Faust than the mundane secularity of the novelistic world.

The decadent writer Barbey d’Aurevilly contended that “Catholicism one day will reclaim Balzac as one of its most devoted and most faithful writers, for in all things he draws the same conclusions a Catholic would draw.” But what conclusions can a Catholic extract from a Machiavellian priest who swaps the analogia entis for the analogy of a game: when trying to outwit friends at cards “Do you practice that finest of virtues, openness? . . . You dissimulate, correct? You lie!” Just so, Herrera preaches, in all of life you must perfect your poker face, for “there are no more laws, just customs, and those are only so much playacting—form, always form.”

In his Preface to the Comédie humaine, Balzac wrote that “Christianity, above all, Catholicism” is “a complete system for the repression of the depraved tendencies of man, is the most powerful element of social order.” Herrera’s character and counsel are especially heinous because he assumes the “form” of Catholicism while liberating Lucien’s depraved tendencies. To paraphrase Aquinas, the greater potentiality a thing has, the more it is disposed for good, the worse it is for that thing to be deprived of good.

Lucien’s fall is hard to witness, but a falsified Father is hardest to find out. For Balzac, the erosion of Catholic order may have been primarily a political tragedy. Nonetheless, if MacKenzie is right that Herrera’s presence is mythical-allegorical, are we wrong to come to this chilling conclusion: when religion’s restraining power withers, it will be replaced not by an enlightened governance but by wicked ambitions unleashed with a logic that assumes pseudo-sacred authorization.

In the sequel Lost Souls (MacKenzie’s rendering of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes), he chases the effects of this erosion to their horrific conclusions: Ferrera (whose real name is not Vautrin but Jacques Collin) continues to manipulate Lucien. Living vicariously through the beautiful boy, he plays his marionette to a death that occasions a secular conversion: “Last night, as I sat holding the cold hand of the dead boy, I made a promise to myself to give up the insane battle I’d been waging for twenty years against society. You won’t expect me to launch into Capuchin-style pieties, not after what I’ve already told you about my religious opinions . . . Well! For these twenty years, I’ve seen the underside of the world, its cellars, and I’ve come to see that in the stream of events there’s a power that you’ll call Providence, and I call chance.” Lucien’s death moves the master of the underworld to abandon his post and make himself “the servant of that power that weighs down and crushes us”—helpmate of the police, those “Providences” of Paris. What are we to make of this about face?

Elsewhere, and often, Balzac does not hesitate to tell us what to think. Early in Lost Illusions, for instance, after painting a portrait of rurality, he tells us that “the most ridiculous things about us are born out of fine sentiments, by virtues or abilities carried to an extreme. A pride that is never smoothed down by contact with society ends up becoming a rigidity that exercises itself on trivialities.” The penchant for moral aphorism is evinced in French writers from La Rouchefoucauld (“If we had no faults we should not take so much pleasure in noting those of others,”) and Pascal (“A trifle consoles us, for a trifle distresses us,”) to Simone Weil (“Evil when we are in its power is not felt as evil but as a necessity, or even a duty.”). One of the delights of reading Balzac is his interplay between intense action and incisive aphorism. But when it comes to his thoughts on Collin-Vautrin-Ferrera, he withholds expressed judgments. Is Peter Brooks right when, in Balzac’s Lives, he argues that “Outlaw and police are just two positions on the social chessboard that can be easily swapped,” that these two positions possess an “essential moral equivalence”?

Even if we contend the that the police, insofar as they serve law and order, are devoted to a superior end, the authorities’ appreciation of Collin’s crime solving swiftness suggests another aphoristic truth: their capacity to contain crime is directly proportionate to their alliance with a criminal. What is unsettling about Collin, Brooks contends, is “that he refuses the distinctions between good and evil altogether . . . what is truly diabolical [about him] is that he puts in question the very idea of social order,” for—like Rousseau—he sees society as a sham social contract wherein law exists to protect the fraudulent. In his preface, Balzac argues the contrary. In spite of the fact that in his novels he has “displayed more of evil than of good,” society, “far from depraving him, as Rousseau asserts, improves him, makes him better.”

Is Collin, then, “improved” in the end? “Now,” he promises, “if you put me into the service of the Law and the police, at the end of the first year you’ll be applauding the revelations I’ll bring you—I’ll be frankly and openly exactly what I should be.” Arguing the authenticity of his submission, Collin appeals to the free character of his reversal: “I’ve given you sufficient proof of my honor,” he says to the prosecutor general, “you let me go free and I returned.”

This free choice, however, is not sufficient evidence of his lawfulness, as his final soliloquy bespeaks the grave risk of relying on a serial felon. Musing upon the upper crust who have gone unpunished, Collin “allow[s] himself a superb smile . . . ‘They all believe me, they all act on the revelations I make to them, and they leave me alone and unhindered. I’m going to reign over this whole world, this world that has already been obeying me for twenty five years.’” Balzac has trained us to abhor the white collar criminal as epitomized in the banker Nucingen, whose dealings are funded by fake bills and whose obsession with Lucien’s lover have hastened the young man’s ruin. Nucingen is a “kind of legal Jacques Colin in the world of écus”; a “man steeped in secret infamies, a monster who in the business world has committed such crimes” that every cent of his fortune is “wet with the tears of some family.” Balzac dares us not to delight in Colin’s plans to punish the fraudulent banker, even if justice is driven by a valet of vengeance.

Henry James called Balzac a “Benedictine of the actual” who “read the universe, as hard and as loud as he could” into whatever his coffee-fueled pen offered up. In Lost Illusions and Lost Souls, Balzac proves himself an acolyte of ambition, immersing us in addled souls who can’t let go until it is too late, subjecting the spirited to catharses and conversion, ridding us of republics writ only in dreams. Practicing his office upon illusive altars, he clears the incense that enshrines Faustian bargains and purges the reader of Paris spleen.