Partisan Democracy

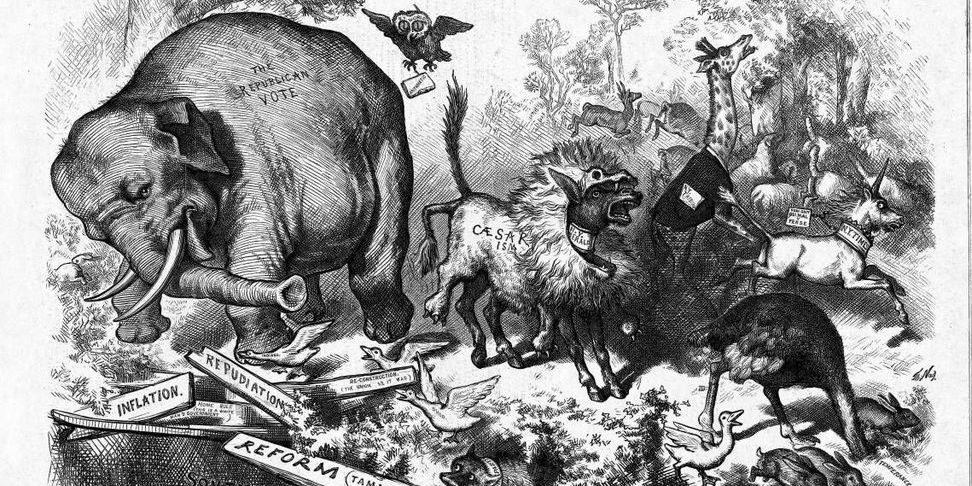

American politics is an ugly business. We should not overstate this, of course. The commonplace claim that “America has never been more divided,” for instance, is ahistorical hyperbole. Nonetheless, we can be forgiven for finding partisan mudslinging nasty, unproductive, and often irresponsible.

The repugnant culture of partisan politics has undoubtedly discouraged countless qualified, talented people from pursuing a career in public service. Although we can always find people who relish “the politics of personal destruction” to stand for office, we may question whether they are ideal advocates of their constituents’ best interests.

Unfortunately, calls for civility often come across as unrealistic and naïve. One might as well ask champion boxers to put a little less force behind their punches. Practitioners of brutal politics can accurately note that politics is an inherently vicious game with high stakes. If you do not like it, stay out of the ring. Besides, if just one side was convinced to follow the path of high-minded civility, it will be to that side’s disadvantage if their opponents fail to reciprocate.

Robert B. Talisse, a philosopher at Vanderbilt University, seeks to resolve this problem in his new book, Sustaining Democracy: What We Owe to the Other Side. He notes that a functional democracy requires citizens to recognize each other as political equals, worthy of civility. For Talisse, political civility is not defined by formal courtesies, and it does not preclude bitter struggles. Instead, civility requires “public-mindedness, reciprocity, and transparency.” More broadly, it means that “citizens do not lose sight of the fact that their fellow citizens are their political equals, who are therefore entitled to an equal say.”

Democracy, Talisse notes, suffers from an unfortunate dilemma. The attributes that define a responsible democratic citizen are also associated with uncivil attitudes and behaviors. We may aspire to the day “when every citizen is an active, sincere, and conscientious participant” in American democracy. Yet these virtues are also associated with our worst political impulses: animosity toward partisan out-groups, distrust, radicalism, and a refusal to engage in good-faith political discussion with our opponents.

“The democrats’ dilemma,” as Talisse calls it, cannot be solved by appealing to democratic theory. Partisans are convinced that political defeat would be disastrous and will not readily concede anything to their adversaries. They are furthermore convinced that their opponents are corrupt and malicious, unworthy of civility. Therefore, Talisse appeals to political self-interest to make his case.

Partisans, Talisse argues, should maintain a baseline of civility because doing so makes them more likely to win. Uncivil, polarized political actors are simply less efficacious. Too often, ideologues form homogenous bubbles, incapable of creating partnerships with groups and individuals that fail to align with every one of their values and interests. These polarized groups become increasingly intolerant of internal dissent, the most radical rise to the top, and the heterodox are sent packing, which only shrinks the group further. According to Talisse, political actors that cannot maintain civility with their opponents will not be able to build effective coalitions with their allies.

To make his case, Talisse relies on recent findings in political psychology, especially research on the nature of polarization. He notes the disconcerting finding that “interactions among like-minded people tend to result in each person adopting more radical versions of their shared views.” As we increasingly retreat into our homogenous political silos, we “become more dogmatic, that is, less responsive to counterevidence and criticism.”

Once again, the problem is not easily resolved. Groups of like-minded people tend to become ideological echo chambers, dominated by the most radical voices. Yet we must join groups to have any kind of political efficacy. Furthermore, the process of joining a partisan community has consequences for our sense of personal identity and way of viewing the world. As we form into political tribes, and primarily receive political information from trusted allied sources, “our conceptions of our rivals tend to be exaggerations and distortions.”

Unless the line between “reasonable” and “unreasonable” is drawn with extreme care and with little ambiguity, partisans will seek to declare their opponents outside the realm of “reasonableness,” freeing them from the obligations of civility

Although Talisse relies on relevant research to make his case, he provides few details about specific studies in the main text, instead directing readers to citations in the footnotes. I wish he had written more about the research that was critical to his argument. Talisse clearly wanted the book to be short and accessible to non-experts, and he succeeded in that goal. In fact, he overshot. I suspect he could have easily included more detail about these studies without confusing readers or trying their patience. A few more pages explaining recent research on the psychology of polarization would have made the argument more compelling.

The dilemmas Talisse points out are real and have been well documented. Unfortunately, Sustaining Democracy provides few viable solutions. Talisse acknowledges that efforts to mitigate these issues—such as encouraging people with different political attitudes and identities to respectfully engage with each other as individuals—have a mixed record. Even if facilitated deliberation of this kind was consistently successful, it is probably not scalable.

Given that there are no obvious institutional or policy changes that will mitigate the problems Talisse identifies, he is left instead with appeals to individuals, changing attitudes and behaviors one person at a time. He insists that he is not calling on people to abandon their principles or become ambivalent moderates. He instead encourages more thoughtful reflection, and a willingness to entertain the possibility that one may be wrong. According to Talisse, “The first thing we must do is recognize the vulnerability of our political commitments to reasonable criticism.”

To help us break free from the worst aspects of partisan group-think, Talisse encourages readers to occasionally step away from political engagement. Yes, a vibrant democracy requires active, passionate citizens, but astute and effective activists must also be, at least some of the time, “reflective and introspective, reserved and thoughtful.” By stepping away from politics, even briefly, we can, Talisse hopes, free ourselves from polarization’s most deleterious, perception-altering effects.

Although Talisse wants to see more civility in American politics, he also concedes that there may be times when civility is a mistake. “Unreasonable” proponents of views that “are incompatible with the fundamental democratic commitment to self-government among political equals” do not require civility.

According to Talisse, “Familiar forms of racism, sexism, and nationalism are among the views that obviously fit this mold.” Although most readers will broadly agree with his assertion that certain political actors cannot be reasoned with and easily incorporated into democratic discourse, this passage in the book may fatally undermine his larger cause.

The desire to view one’s political opponents as irredeemably wicked, and thus unworthy of civil treatment, may prove irresistible. Indeed, I imagine many of Talisse’s readers will say they agree wholeheartedly with his analysis and recommendations, but nonetheless insist that their enemies have already crossed that particular Rubicon. Thus, in their view, they have the right (and perhaps obligation) to take the gloves off and fight dirty.

I assume Talisse does not consider most Republicans, including most Trump supporters, to be “unreasonable” according to his own definition. The book would make little sense if he did. However, much of the left—perhaps a majority of left-wing activists and opinion leaders—eagerly declare their opponents racist, sexist, and even fascistic. As long as they believe these monikers are deserved, they have little reason to pursue civil discourse with their opponents, according to Talisse’s own argument.

Unless the line between “reasonable” and “unreasonable” is drawn with extreme care and with little ambiguity, partisans will seek to declare their opponents outside the realm of “reasonableness,” freeing them from the obligations of civility. The book unfortunately provides little advice for readers who want to know how Talisse would determine who belongs in each category. Rather than provide a list of attributes we can use to determine whether an opponent is outside the bounds of reasonableness, he considers it sufficient “to set forth an intuitive view of what makes a view unreasonable.”

Further confusing matters, Talisse is vague about how we should engage with political opponents after concluding that they hold views incompatible with democracy. He again gives little guidance, only suggesting that some views are so abhorrent that attempting to put them into practice should be criminal, whereas others may require “begrudging tolerance.”

Talisse hopes that citizens who follow his advice will be in a better position to disaggregate people who are “severely misguided but nonetheless reasonable political opposition and those who are truly beyond the pale of the democratic ideal.” I consider this unlikely. Righteous fury can be an agreeable feeling. The belief that one is engaged in a Manichean struggle against perfidious enemies can provide meaning in an otherwise uninteresting existence. Few people will be eager to give up either, even if their partisan enemies are, objectively, not that bad.

Sustaining Democracy contains many important insights, and readers will be wise to heed its advice. I am nonetheless skeptical that Talisse will convince many Americans to change their approach to politics. This is not necessarily a pessimistic prediction. Exemplars of the uncivil polarization Talisse describes, the irritable activists on the far left and far right, often stand for terrible politics and policies. I do not want them to be more effective. Perhaps the best-case scenario is that Talisse is correct, their boorish approach to public affairs results in political defeat, and, failing to learn any lessons, they continue forever down the path of self-marginalization.