In Search of a Presidential Theory

Is the US president’s administrative control over key portions of his administration the most important contributor to the success of his presidency? What about other factors, such as the president’s political judgment, his ability to formulate and implement policies, and his skill in communicating with the American people?

Patrick O’Brien writes in his introduction to Presidential Control Over Administration: A New Historical Analysis of Public Finance Policymaking 1929-2018: “The central argument of this book is that presidential control over administration is a foundational component of policymaking and operates as a historical variable.” By the term “historical variable” he means that this factor changes from president to president, and affects the president’s success in relation to other presidents. The thrust of his argument is that successful presidents take “administrative control” over and change personnel or policies in important sectors of the government during their presidencies.

This is an ambitious theory, and to cut it down to a manageable size the author limits the scope of his review to what he calls “public finance,” comprising the budget—taxing and spending—and monetary policy. This choice undoubtedly made it more difficult to pinpoint each president’s role in the changes that occurred in his administration. The president, after all, has to rely on the legislature for taxing and spending policies, despite preparing a budget and making recommendations to Congress. Moreover, monetary policy is under virtually complete control by the Federal Reserve, which is the most independent agency in the executive branch. Both elements limit the president’s options.

If Mr. O’Brien had chosen, say, defense policy or foreign policy it might have been easier to demonstrate how particular presidents administered or changed policies in those areas, but this book was developed out of his work as a graduate student at Yale, and what his journal articles have been about. Still, Mr. O’Brien makes a strong claim for the argument in his book. He describes it as “a theory of historical variation in presidential control,” by which he seems to mean that the presidents who take administrative control of their policies and/or personnel are successful, while others are not.

All presidents, he argues, have to deal with certain realities. The first is time. In general, the president does not have enough time during his presidency to change the established administrative structure that was present when he took office. Except under unusual circumstances, he must work with the administrative structure that was there when he arrived. Next is personnel. Except for the relatively few people he can appoint to the major positions in his administration, the president must rely on the assistance or compliance of people already in place. Finally, the president must live with other powerful forces within the government. Congress, for example, has the power to stifle his initiatives, refuse to confirm his nominations, or deny the funds he needs for the policies he has in mind.

Then, after these obstacles, the president has to perform well enough with all his responsibilities to meet the expectations of the public and to implement the policies he campaigned for and reflect the views of his political party.

All this makes sense, but what’s the effect of the author’s theory about administrative control? This isn’t made entirely clear, unfortunately, but appears to be that presidents have only two options. The first is constraint, which occurs when the problem the president confronts is not exceptionally severe or highly prioritized. In that case, the president will likely decide to rely on the existing administrative apparatus to meet his political needs, even though it may not function as well as he would like. The second and most important is innovation, in which a president confronts an exceptionally severe or highly prioritized problem, which will drive him to substantially strengthen his administrative control by “working to restructure both the established administrative apparatus and the established policy parameters.”

The key question, then, is whether a president recognizes that he is confronting an exceptionally severe or highly prioritized problem. If so, which depends very much on his own political judgment, we can—according to Mr. O’Brien—predict what the president will do. He will take the time to change either the administrative structure or the governing policies, or both. That seems to be the theory.

Is it useful? Probably not. It’s useful to know what a president considers an “exceptionally severe or highly prioritized problem,” but how he responds to it is the key to determining the success of his presidency. It’s the quality of his decision-making when he takes administrative control of personnel or policy—inflected by his political and persuasive skills—that will make the difference between success and failure.

What the president actually does—whether he has the political skill to choose the right policy, and the fortitude to stay the course as his policy unfolds—will ultimately determine whether his presidency is a success.

Take our current president, Joseph R. Biden. If we use current news as an example, he has several major problems—inflation, gasoline prices, a war in Ukraine, crime in the cities, a baby formula shortage, an open border with Mexico, and weak economic growth, to name just a few. Any one of these problems would normally be serious and high priority enough to produce some of what Mr. O’Brien calls “innovation”—changes in the administrative apparatus or policy.

But since Mr. O’Brien limited his discussion primarily to fiscal policy, it would be fair to consider what President Biden is doing in the way of “innovation” to deal with inflation. To be sure, most economists would say that much of the inflation problem has been created by the Fed’s monetary policy, but Mr. Biden’s policies, principally his sponsorship of the $1.9 trillion “American Rescue Plan” at the outset of his administration must share part of the blame.

According to Mr. O’Brien’s theory, then, this would be a point where an ultimately successful president—confronted with a problem as severe as today’s inflation—would start to innovate, However, as recently as his State of the Union address, President Biden was still calling for Congress to enact his Build Back Better plan, which had been scored by the Congressional Budget Office at about $5 trillion when priced out over the ten years it would likely be in place. As many have noted, this would seem likely to make his inflation problem worse. In other words, Biden’s actions or inactions don’t seem to match up with what one would expect under Mr. O’Brien’s theory. Where this president should have innovated either in administrative apparatus or policy, or both, he has done almost nothing. This would indicate, under Mr. O’Brien’s theory, that Biden will be an unsuccessful president.

However, that does not tell us much. If Biden had “innovated” at this point in his presidency, there would still be major questions about the actions he might take. These would depend on whether his policies and his political skills actually enable him to deal successfully with inflation. These are unknowns, so that merely innovating—changing policies and/or personnel—is not enough to determine whether his presidency would be considered successful.

This is potentially a serious flaw in O’Brien’s theory. It gets us only to the point where the president acts, but everything beyond that is what will determine whether he is a successful president.

Let’s examine the theory from the other side—a president who came into office at a time when there was a severe fiscal problem, but not of his making. This would be Ronald Reagan in 1980, who succeeded Jimmy Carter in the midst of a period of very high inflation. At this point, the Fed was headed by Paul Volcker, who had raised interest rates to between 16 and 18 percent in order to bring inflation under control.

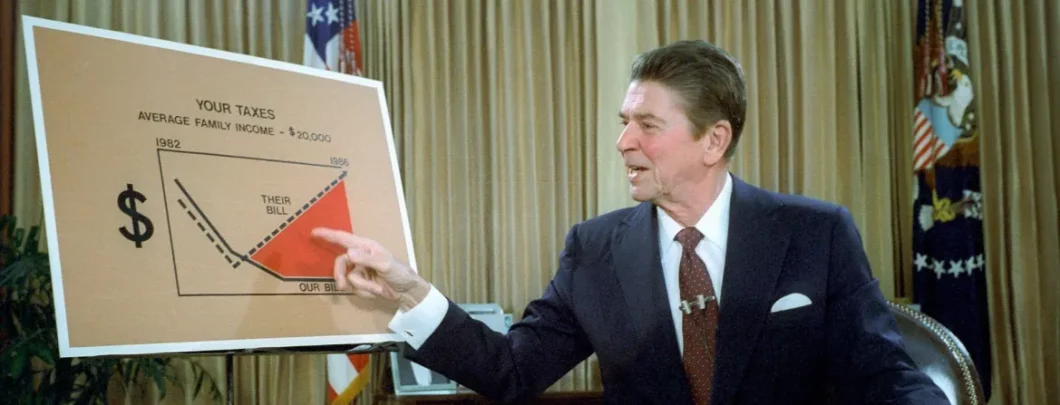

Under Mr. O’Brien’s theory, President Reagan should have immediately turned his attention to dealing with the inflation crisis. He did this—matching what Mr. O’Brien’s theory says a successful president should do—but the policies he adopted were highly unconventional and risky. The expected policy would have been raising taxes and balancing the budget. That would have been consistent with traditional Republican tight money policy, and with most conservative economists’ view that the massive inflation the country was experiencing was in substantial part caused by budget deficits—that is, spending more than the government was taking in through taxes. Instead, Reagan adopted a completely different set of policies, by raising military spending and stimulating economic growth through tax cuts. Both were inconsistent with cutting spending and balancing the budget, but those are the policies that Reagan pursued anyway.

His theory—called supply-side economics at the time—held that cutting taxes would stimulate economic growth, and that in turn would produce enough revenue over time to sustain increased military spending. In the off-year election of 1982, with little to show for these policies and unemployment touching ten percent, the GOP lost control of the House. But by the second half of 1983 strong economic growth had begun and Reagan had the pleasure of saying “Well, they don’t call it Reaganomics anymore.”

This suggests that Mr. O’Brien’s theory does not carry us beyond the first steps—the necessity for a president to act when he confronts a major problem. But what the president actually does—whether he has the political skill to choose the right policy, and the fortitude to stay the course as his policy unfolds—will ultimately determine whether his presidency is a success.