Colin Dueck discusses his new book, Age of Iron, with Richard Reinsch

Recovering a Constrained Foreign Policy

The American diplomat and strategist George Kennan posed a critical question in 1950 by asking why the United States then felt so insecure. While political and military realities of fifty years before had provided security unmatched since Rome, the early Cold War was “dangerous and problematic in the extreme.” This remarkable metamorphosis prompted Kennan to look into the recent history of foreign policy which he wrote in a short volume entitled American Diplomacy, now still in print.

Angelo Codevilla takes up those concerns with a wider focus and sharper critical tone in America’s Rise and Fall Among Nations. Published after his death last year, the book indicts policy failures in recent decades which he contrasts with an older tradition of statecraft that had secured the United States’ emergence as a great power. American foreign policy, Codevilla forcefully insists, should secure the country’s “separate and equal place among the nations of the earth” by cultivating peace and harmony with other states. But instead of following this path, he continues, the United States has chosen a foreign policy that has made it less secure abroad and more divided at home.

The Italian-born Codevilla stood outside and increasingly against the American establishment. Briefly in the US foreign service and before then a naval officer, Codevilla became a longtime congressional staffer on the Senate Intelligence Committee for the conservative Republican Malcolm Wallop. The hardline Cold Warrior advised Ronald Reagan’s presidential transition and later worked on the Strategic Defense Initiative. Codevilla knew government from the inside with deep knowledge of history and political theory sharpening his criticism of its failings. He thought establishment insiders had been too soft on the Soviet Union during the Cold War and then too expansive later in waging a war on terror. Neither policy set America’s interest at the center as he argued from the Claremont Institute and other platforms.

Far from evoking a lost arcadia in the American Founding, Codevilla takes an unflinchingly realistic view of the world and focuses on key questions of national interest and the meaning of peace. His historical account parallels work by Walter McDougall, but the analysis follows Thomas Sowell’s distinction between tragic and utopian outlooks, where Sowell’s constrained vision starts with an unchanging human nature driven by self-interest as opposed to utopians who want to transform reality. Rejecting or downplaying empirical understanding, especially when refracted by tradition, utopians rely on abstract reasoning, credentialed expertise, and a willingness to act. Instead of providing fixed principles, utopians follow prevailing trends and passing enthusiasms. Codevilla sees their lack of principle as a fatal flaw. It makes the ship of state a vessel with all sail and no anchor that inevitably runs onto shoals. He accordingly aims to restore the missing ballast.

No Entangling Alliances

Codevilla draws his principles to guide American statecraft from early efforts to secure independence from Britain and uphold it in a hostile world. George Washington and other founders envisioned the United States as a nation apart from Europe with its conflicts while engaged in the world through peaceful commerce. Americans sought freedom from unnecessary conflict to pursue happiness by attending to their own affairs in a country where cheap and available land and generous wages provided opportunity. Independence and republican self-government empowered individuals and allowed communities to manage their affairs free of external interference. Religious liberty ensured Americans could serve God as their conscience directed. Only defending a peaceful independence that served those ends, Codevilla insists, justified war.

In a 2014 reflection on the nature of peace, Codevilla called it both the logical focus of statesmanship and the natural end of humanity. He struck a different note from Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan which famously described man in a natural state without government as in a war of all against all. Codevilla’s argument that war served the natural end of peace looked back to Aristotle and Christian thinkers like Augustine. While honor, interest, and ideas drove men into war, they fought to achieve goals set by them and not for the sake of fighting alone. Conflict as an end itself rather than means suggests either the berserk madness of savages or bureaucratic absurdity of Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. The eighteenth-century world understood war as a limited activity upholding rights or protecting interests to secure a favorable peace. That peace, the jurist Emer de Vattel pointed out, put the settled dispute into the past so parties could live henceforth on good terms.

Americans who had fought a devastating war for independence stood ready to defend their honor and safety, but they sought to avoid conflict where possible. Besides recognizing the value of peace, they knew from experience war’s unpredictability. The Roman dictum that if you want peace, prepare for war captured a deterrent approach Washington stressed. Codevilla cites John Jay in Federalist 3 and 4 on the need to avoid giving foreigners insult or injury while deterring their interference with American affairs by threat of retaliation. In Federalist 6, Alexander Hamilton pointed out that since wars arose from ubiquitous and unpredictable circumstances Americans should always be ready to fight. He also drafted the warning against entangling alliances that might draw the United States into the conflicts of other powers in Washington’s Farewell Address. The Federal Constitution ratified in 1788 sought to bind the states more closely into an effective governing system and thereby enhance the nation’s power. Peace stood out as the consistent aim.

Codevilla described the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars as “the crucible in which the American people’s international character was formed” because it tested both independence and unity. Events in France divided Americans even before the start of the European wars that lasted until 1815. Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson struggled to keep the United States from being drawn into it or becoming the pawn of either side. Reciprocity, a key principle demanding respect for American rights and interests while recognizing those of other states, became hard to uphold. The War of 1812 amounted to a second war of independence from Britain, but it also cast the United States in the awkward role of Napoleon’s co-belligerent. Escaping it without lasting divisions or loss was a near miss.

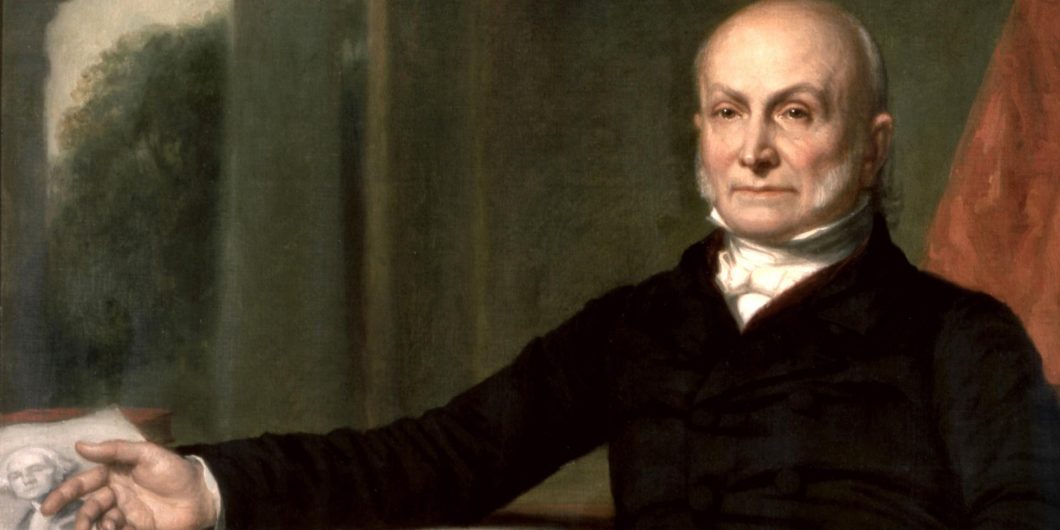

John Quincy Adams, who as a ten-year-old accompanied his father on a diplomatic mission to Europe in 1777, distilled the experience into lasting principles and showed how to apply them. He laid the foundation for American geopolitical thought in distinguishing the causes for which the country should fight by importance and proximity. The most relevant interests were usually where the United States had leverage to promote them. Adams’ diplomacy sought to clarify objectives meticulously as the basis for both policy and discussion. Codevilla emphasizes Adams’ pragmatism in following how timing and space affected the stakes in particular cases to strike compromises that secured American aims without conflict. Not just principles, but their application mattered, too.

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 illustrated Adams’ approach with lasting effect. Codevilla describes it as a statement of mutual non-interference extended to the whole Western Hemisphere. Distinguishing the United States’ political system from that of Europe, Adams sought to exclude new European colonies from the Americas while staying out of disputes across the Atlantic. Since Continental European powers lacked the means to intervene, especially against British opposition, he risked little while defining a vital interest as a future deterrent to foreign involvement. The alternative of cooperating with Britain as Foreign Secretary George Canning proposed risked compromising the principle of upholding republicanism in the New World and subordinated American interests to a partner likely to run over them.

Adams’s determination, as Codevilla puts it, to mind America’s business while keeping out of the business of others provided a lasting guide. Codevilla lists Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, and William Seward among the keepers of his legacy in foreign policy. He also describes figures with a very different outlook like Andrew Jackson and John C. Calhoun both of whom accepted the limits of American power. Jackson, determined to neither do nor suffer wrong, sought good relations with other powers. Calhoun resisted taking over Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula in 1848 as the precedent would justify Europeans to intervene elsewhere or use the threat to push the United States into preventive action. Clay thought abandoning the Monroe Doctrine’s principle of amity and non-interference toward Europe would end great power forbearance toward the United States. Speaking in 1885 of a “policy of peace suitable to our interests,” Grover Cleveland defined it as “honest friendship with all nations; entangling alliances with none.” While American power grew over the 19th century, the principles Adams framed still guided the nation’s foreign policy.

Codevilla makes a strong case for turning away from the unconstrained vision of American progressivism and concentrating instead on practical issues. Castigating elite failures—particularly the charge of turning away from the nation-state—is required for self-governance.

The Right Side of History

Imperialism in the 1890s broke with that tradition to set a lasting pattern that framed foreign policy around moral uplift rather than national interest. The general approach outlasted imperialism, which proved disappointing even to some advocates like Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge. Here, Codevilla would have served readers better by defining progressivism clearly rather than leaving them to piece together its origins and outlook from his narrative.

Drawing on German idealists like Hegel, progressives embraced state action under expert direction to improve society and liberate individual potential. Americans who studied in Germany transformed their universities’ institutions to pursue secular research on scientific principles. Indeed, natural science became the benchmark for expertise. Moral reform before the Civil War also shaped progressivism by fostering a millenarian sensibility increasingly detached from biblical Christianity. The influential Social Gospel movement from the 1880s lost sight of the Christian Gospel in its determination to reform society. One of its founders, Josiah Strong, Codevilla notes, saw the United States as the center of a progressive dynamic with global reach. Few programs, in Sowell’s terms, could be more unconstrained than this vision that advocated changing the world instead of improving one’s self.

Progressives emphasized systems as the means to secure both reform and peace. Business administration in the large corporations that dominated the growing 19th-century American economy offered a model of scientific management to apply more broadly. By contrast, legislative bargaining, federalist checks and balances, and local particularism represented impediments to progress in the United States. Abroad progressives looked to international law to enforce peace through binding arbitration and multilateral agreements. Kennan had criticized American diplomacy’s “legalistic-moralistic approach to international problems.”

Codevilla makes the point a central theme with Elihu Root as a key figure in setting a global order defined by international law above national interest. He argues that Root framed progressive foreign policy much as Adams had framed what came before. A modernizer as Secretary of War and then State, Root won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1912 before leading the Carnegie Endowment and foundied the Council on Foreign Relations. Codevilla emphasizes Root’s mentorship of Henry Stimson, the Republican lawyer-statesman who served administrations of both parties and later promoted McGeorge Bundy. The political genealogy continued to Bundy’s protégé Anthony Lake whose influence extended to Barack Obama’s administration. Root sought to institutionalize global order through multilateral bodies that would enforce international law and thereby prevent war. The US Senate’s rejection of compulsory arbitration treaties he negotiated seemed an attack on progress. How could humanity move forward when resistance blocked the way? The argument would only become stronger after the catastrophe of World War I.

The diplomatic historian Paul Schroeder pointed out that the United States benefited greatly from the long European peace between 1815 and 1914. No major wars among the great powers like those of the 18th and 20th centuries threatened America’s peace. The situation aided the United States’ political development and made the Adams tradition easier to pursue than in a more contentious environment. Woodrow Wilson revealingly likened his position during World War I to James Madison’s predicament amidst the Napoleonic Wars. He and other progressives—Democrats and Republicans alike—focused on framing a global order to secure peace with mixed success. Their emphasis on institutionalizing systems and decided preference for those they deemed to favor progress over anything perceived to impede it set a lasting pattern in American foreign policy. Being on the right side of history mattered.

Codevilla laments the habits of tinkering with foreign problems American officials developed. Military expansion laid the foundation for a national security state in the 1940s. Universities and private think tanks established in the 1930s advised policymakers as diplomatic infrastructure grew. These institutions had priorities of their own and competed for influence within the larger government bureaucracy. Periodic crises gave authority to experts who specialized in managing emergencies according to the latest best practice. Foreign policy became a big business where “clashes of ideology, identity, and interest” within the American establishment mattered more than public opinion. Citing expert advice dodged accountability, especially where Congress deferred to the executive rather than risk taking controversial positions.

Elites for the Public Welfare

Codevilla draws a sharp contrast between historical periods in American foreign policy to make his case for returning to the path Adams had blazed. A narrower vision grounded on national interest has more chance of success than the unconstrained pursuit of global order. His deft sketches of episodes since World War II serve readers well by showing the consequences of progressive shortcomings. Wrong choices brought failure or squandered opportunities to capitalize on success. Charles de Gaulle’s description of the Kennedy administration as “not serious” after its bargain to end the Cuban Missile Crisis, which gave up the chance to secure key objectives, captures an important theme for Codevilla. His persistent critique of elite fecklessness echoes James Kurth’s description of post-Cold War American supremacy in the 1990s as an adolescent empire that substitutes vigor and emotion for prudence and judgement grounded in experience. Serious leadership appreciates context and engages practical issues to avoid debacles like Iraq where policy not thought carefully thorough falls apart. Codevilla’s polemic resonates here even where it invites criticism on other points.

Despite strong prose and evocatively presented episodes, Codevilla leaves some points for the reader to fill out themself. What specifically is the ruling class? Who are they? What is what Obama advisor Ben Rhodes famously called “the Blob”? Is this a different group from the so-called “wise men” who guided policy after World War II or their successors in the 1960s who were responsible for the debacle of Vietnam? Progressive thinking became the default with other voices, like Robert Taft, marginalized. But different, sometimes conflicting strains of thought operated within that consensus.

Explaining the differences Codevilla mentions within the American establishment, including those seen over time, would strengthen his critique. Not doing so gives critics openings to challenge his larger view and makes sympathetic readers less able to grasp where things went wrong.

Codevilla does better as critic than offering an alternative for the present. While he emphasizes national interest and treats peace as an aim rather than as an ongoing process resonates, his specific proposals are mixed. Abrupt disengagement from Europe, Northeast Asia, and even the Middle East creates its own problems, and Codevilla’s suggestion of letting regional conflicts burn themselves out is easier said than done. Offshore balancing to protect interests while minimizing liabilities works better than a sharp break. The legacy of conflicts since World War I and the upheavals it brought produced a more complicated environment than the 19th century Pax Britannica that shielded America’s rise.

Codevilla rightly focuses on the Western Hemisphere where threats from instability have been neglected, but how to protect American interests without being drawn into larger commitments needs explanation. He channels Niccolò Machiavelli as a guide for ruthlessly deploying force to secure peace without realizing the difficulty of making Florentine realpolitik fit in a very different American culture. Escalation also risks expanding conflicts and making a favorable peace elusive. Adams’ principles require care in their application to be effective. Codevilla risks at times falling into the same trap as the progressives he criticizes by offering solutions that work better on paper than in reality.

Nevertheless, America’s Rise and Fall Among Nations makes a valuable contribution to debate. Codevilla brings into focus the failings of dominant thinking about foreign policy and shows where it broke from earlier practice. He makes a strong case for turning away from the unconstrained vision of American progressivism and concentrating instead on practical issues. Castigating elite failures—particularly the charge of turning away from the nation-state—is required for self-governance. Elites, like the poor, will be always with us. What we need, from Codevilla’s perspective, is a new elite operating on better principles with an eye to the public welfare.