Scapegoating Newt

Julian Zelizer is an esteemed and accomplished historian. He is the author or editor of over twenty books and holds an endowed chair at Princeton University. His books on Congress have won national awards and his earlier books on Congress’s history, including Taxing America: Wilbur D. Mills, Congress, and the State, 1945-1975 and On Capitol Hill: The Struggle to Reform Congress and its Consequences, 1948-2000, are essential reading for those wishing to understand the development and decline of Congress over the past century.

These earlier works set a high bar for careful scholarship and analysis. Unfortunately, Zelizer’s recent book on congressional development, Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of the New Republican Party, fails to meet that standard by a significant margin. In the interest of telling a compelling story to a popular audience, Burning Down the House sacrifices the care and caution that commend Zelizer’s other books.

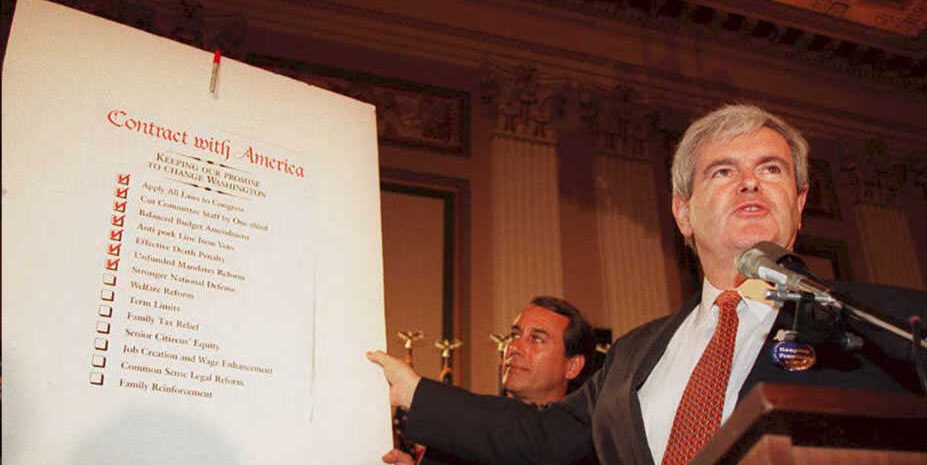

The thesis of Burning Down the House is that contemporary partisan dysfunction is the result of a new strategy of confrontation adopted by Newt Gingrich as he rose to power in the 1980s. Gingrich’s aggressive strategy alarmed Republican Party leadership, but the tactics enhanced the Party’s electoral prospects so greatly that Republican leaders reluctantly accepted them.

If you feel like you’ve heard this story before, it’s because you probably have. It is common in popular articles and books to suggest that Newt Gingrich broke American politics. Gingrich’s much-maligned crusade to bring down House Speaker Jim Wright (D-TX) on ethics charges is often portrayed as the central event in the tale.

Zelizer’s portrayal follows this pattern of treating Wright’s resignation as the critical event that gave rise to contemporary dysfunction: “The Wright scandal was the beginning of this end, and its shadow looms large and grows longer with each passing day,” he writes. Wright’s resignation paved the way for Gingrich, who in Zelizer’s telling “had practically written the handbook on cutthroat congressional tactics and spinning the media for partisan advantage,” to emerge. Over time, more and more of his Republican colleagues “were drawn to the bare-knuckle legislative style that Newt Gingrich had pioneered.”

The ultimate end of Gingrich’s vision, unsurprisingly, is Donald Trump. Zelizer connects Gingrich to Trump with none of the subtlety of his other commendable books. Gingrich, Zelizer alleges, “found Trump exhilarating,” in no small part because Gingrich “had good reason to feel that Trump would never have become the nominee without him.” In fact, Trump’s style of campaign, “which aimed to tear down the leaders of both parties and to destabilize the entire U.S. political system, was Gingrich’s creation.” Gingrich, in this portrayal, is the prime mover of 21st-century American politics, the creator and cause of the most disruptive domestic political force in this century. Offering a metaphor that is curious on many levels, Zelizer writes that “Gingrich would always be Michelangelo to Trump’s David.”

Zelizer frequently attributes motivations to Gingrich in a way that is particularly jarring, especially considering that he never actually interviewed Gingrich for the project. Using Gingrich’s appearance on Hannity in the fall of 2016 as a vignette, Zelizer explains that for Gingrich “the thrill of politics was like a narcotic.” “The best of times” for Gingrich since his resignation in 1998, according to Zelizer, were his appearances on Fox News or when he “filled the role of resident policy wonk at the conservative Heritage Foundation.” The latter claim is especially perplexing, because in my years working at Heritage (2007-2010) and serving as a resident fellow there (2017-2018), Gingrich and his policy ideas were rarely discussed.

Unlike his earlier subjects, Zelizer also makes little attempt to hide his contempt for Gingrich. He casually affirms Speaker Wright’s assertion that Gingrich “was like Joseph McCarthy. The difference,” he explains, “was that the Wisconsin senator had been quashed within a few years in the early 1950s, whereas Gingrich climbed all the way to the top. His rabid political style became the echo chamber of the Republican Party.”

This being said, various chapters in Burning Down the House do cover the stages of Gingrich’s rise to the Speakership and the escalating political conflict that preceded his speakership. While they don’t cover much new ground, they effectively tell a story about the emergence of a new era in Washington, defined by party antipathy and escalating hardball tactics.

No single person or single party broke Congress. While one can learn much about the events and the choices that led us here from reading Burning Down the House, there are far better alternative accounts.

On occasion, these chapters of Burning Down the House find other actors to blame: Jim Wright for his frequent provocation of Republicans during the 1980s, and Republican Party leaders in the 1980s for allowing Gingrich to rise through the ranks. Often these attributions are buried in footnotes, as when Zelizer contrasts his book with another book on the Wright resignation (John Barry’s The Ambition and the Power) by explaining that he believes “the Democrats played a bigger role in the outcome, both through the limits of the reforms they adopted in the 1970s and through the pressure they decided to put on [Wright].” Zelizer quotes a story from the Washington Post explaining that Speaker Wright’s “fiery partisanship and hell-for-leadership style already have polarized the House,” before his resignation.

These brief moments provide glimpses of a deeper and more accurate account of what’s happened to Congress over the past decades. They indicate that Gingrich’s tactics in the 1980s did not emerge in a vacuum. His tactics were as much an effect of the environment that preceded him as they were the cause of escalating partisanship. And many of these decisions that led to Gingrich were adopted by liberal Democrats in the mid-1970s.

This more complicated yet more accurate account of how we got here, however, is deemphasized in Burning Down the House. Zelizer is right to point to developments that preceded Gingrich as pivotal moments in the story he is telling but Burning Down the House doesn’t pay sufficient attention to many of them.

The scholarship exploring the causes and the timing of congressional polarization is vast but has reached something of a near-consensus: the “reform period” of the mid-1970s was a critical turning point that set Congress on its current path. During that period liberal reformers in the Democratic Party, a new kind of “amateur Democrat,” decentralized power in the hands of more homogeneously liberal rank-and-file members of Congress. They also succeeded in instituting direct primaries to ensure that party nominees reflected the wishes of their party’s base rather than the more moderate candidates preferred by party leadership. More recently, voters have started sorting themselves ideologically into similar communities, leading to districts that are increasingly purely “red” and “blue.” Representatives from these districts have fewer incentives to govern responsibly and more incentives to pander to their base.

These reforms and developments have the foreseeable effect of making both parties more monolithically liberal and conservative. As empirical studies of congressional voting behavior indicate (admittedly measured by imperfect “DW-NOMINATE” scores), the two parties started sorting themselves into ideologically homogeneous groups well before Speaker Wright was ousted in the late 1980s. These are structural and institutional causes that run much deeper than any one person’s ambition. Zelizer’s haste to portray Gingrich as the evil genius of American politics leads him to undersell the more complex and deeper causes of contemporary polarization.

In short, Zelizer tells an engaging but a misleading story. Newt Gingrich didn’t break Congress. No single person or single party broke Congress. While one can learn much about the events and the choices that led us here from reading Burning Down the House, there are far better alternative accounts.

This is more than a quibble about properly assigning blame for the situation we are in today. It is about properly understanding the depth of the causes of contemporary dysfunction. An incorrect diagnosis usually leads to a flawed prescription. Zelizer’s account, unlike other, better books I have reviewed for this site, neglects the deeper systemic issues that plague American politics. Consequently, the reader is likely to draw the wrong conclusions about what to do. If it’s the Republican Party, and the ambitious, self-seeking politician who corrupted it, that “broke” American politics, then the only thing we need to do to “fix” American politics is to shame and rebuke Gingrich and his Party.

Such an assessment of the illness and the remedy would, of course, produce exactly the opposite effect of what it intends. If progressive intellectuals and political leaders believe that the fault lies entirely on one party and its leaders, then they would be justified in taking extraordinary steps to delegitimize and destroy that party and its leaders. Such an approach would likely provoke and radicalize that maligned party and its leaders, exacerbating the conflict rather than eliminating it. The constitutional hardball would not stop, but would intensify.

It is true that the forces least interested in compromise are in charge in Congress today. Reversing the contemporary trends of polarization and dysfunction in the halls of our capitol requires a serious consideration of their structural and institutional causes. Yet if that problem is to be solved, it will not be by overly simplistic characterizations assigning total blame to one person and one party. Such accounts will not help to advance the cause of moderation and responsible governance.