Solzhenitsyn's American Millstone

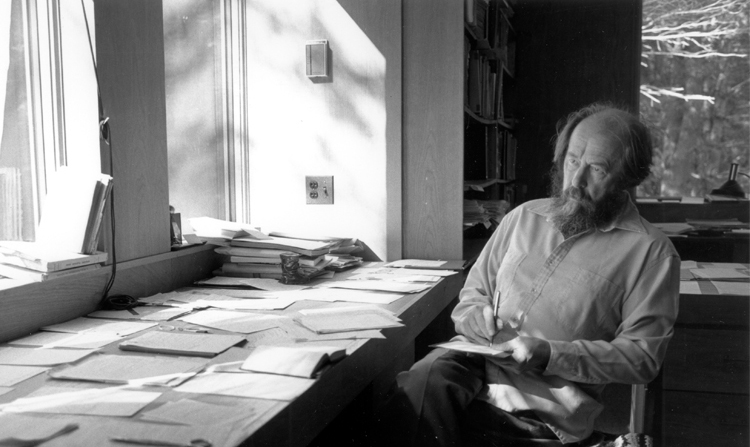

Outsiders see things those on the inside cannot see. Alexis de Tocqueville penetrated American democracy as no American could. In a similar fashion, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Between Two Millstones: Exile in America, 1978-1994 presents a view of America that few Americans could have grasped.

Millstones grind grain into flour, and Solzhenitsyn’s focus is on how the two great political systems of the mid-20th century grind the human soul into dust. One millstone was Soviet tyranny, which Solzhenitsyn dissected in The Gulag Archipelago. The other millstone is Western democracy, which, Solzhenitsyn warns, simulates the Soviet tyranny. Two Millstones focuses on the Western millstone.

The Solzhenitsyn of Gulag is charitable and magnanimous, and indignant in turn. He sought to identify the mechanisms in human nature that allowed the gulag to persist. Surviving in the Soviet system is corrupting to the soul—and who can be blamed for wanting to survive? “Let the reader who expects this book to be a political expose,” he writes in one of the most moving portions of Gulag, “slam its covers shut right now.” Solzhenitsyn recognizes himself in the “blue caps” who take prisoners to the gulag because they had much to live for and wanted to survive. It was easier for him to be courageous since he had nothing to lose.

But the greatness of soul that draws us to Solzhenitsyn in Gulag is muted in Millstones. The Western millstone grinders seem pettier than the Soviets. Solzhenitsyn dives into the gutter about unsubstantiated accusations, slights, treacherous friends or ex-pats, name-calling, and prejudicial journalistic coverage. Solzhenitysn is less charitable to reporters of the New York Times, gold diggers, or hostile academics than he was to the gulag prison guards and blue caps. Does the line between good and evil run through the hearts of New York Times columnists? Are Westerners somehow less human than the apparatchiks of the gulag?

This newly released second volume of Millstones begins after Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard speech, where he criticized the decadent West for its lack of civic courage. The volume does not treat the great geopolitical events of this period, save for the collapse of the Soviet Union. Instead, it covers how Solzhenitsyn and his work were treated in the West during this time. The forgettable lowlifes created a narrative that ground Solzhenitsyn to pieces. He was said by turns to be a monarchist, a reactionary filled with messianic moralizing, an anti-Semite, a neo-fascist, an ardent nationalist, an Ayatollah of Russian Orthodoxy, a fanatical Lenin of the Right, and a warmonger.

When Solzhenitsyn tried to craft a more benign view of Russia as a victim of Soviet communism, he was labeled an unqualified nationalist. When he mentioned that all political communities needed God in order to combat materialism, he was a theocrat. Logic did not matter, since he could not easily be both an unqualified nationalist and an unqualified theocrat simultaneously—since each commitment would in some sense qualify the other. Western politics operates within the narrative’s shadow where people were more interested in the narrative than the truth. No lover of truth could find that congenial.

Western apparatchiks sold their souls to an ideology just as communists did—but without the cynicism and with the confident certainty that every word from their lips was blessed by history.

Solzhenitsyn’s literature was published in the West, unlike in the censorious Soviet Union. That’s different. But his “literary life” fell within “the scope of Hearings and Investigations” first by private outlets that directed opinion and then by public outlets that demanded “advanced censorship.” His books were filtered through the narrative and intentionally mis-read, with unkind, intolerant, unreasonable and (ultimately) embarrassing reviews in the West. “When slander offers them an advantage, do these two world forces,” Solzhenitsyn asks, “differ from one another all that much? In their attacks on me, the Americans are catching up to the Soviet authorities… Even at the height of the battle at the Secretariat of the Writer’s Union, I was not inveighed against with such bile, such personal, passionate hate, as I was now by America’s pseudo-educated elite.” The American press was no less powerful than Pravda in dictating the narrative. There was a difference though: purveyors of the West’s lies were filled with sanctimony while Pravda’s liars were merely cynical.

The usual suspects hounded Solzhenitsyn when he went on Radio Liberty, America’s broadcast into the Soviet Union, with accusations of phantom anti-Semitism. As a result of “Alarm in the Senate” (Chapter 13), bureaucrats stopped his “name even being mentioned on Radio Liberty, and did so just as thoroughly as, until then, only the USSR had done.” Elites demanded advanced censorship of all future Solzhenitsyn broadcasts on Radio Liberty to protect against his alleged anti-Semitism—and the government, under the Reagan administration, no less, obliged. Would it be long until corporations followed suit, under the pressure to maintain the narrative?

Solzhenitsyn wrote about the narrative in “Our Pluralists” (a 1983 essay). Elites of western pluralism, he argued, all came from the same set. “All lived for decades in the capitals, and several of them served as. . . Marxist philosophers, feature writers, lecturers, cinema directors, or radio producers” indistinguishable from “the Central Committee men and the Cheka men, from the Communist regime.” If Solzhenitsyn spoke, his words were mediated through their narrative; if he was silent, the narrative filled in the blanks. “What kind of democracy,” Solzhenitsyn asks, “what kind of conscience is it that inveighs against someone not for what they said but for what they didn’t say?” No kind of deliberative democracy, for sure.

Courts were also implicated. Solzhenitsyn was subjected to a trial for libel from Olga Carlisle, a former friend and associate. To fight the charge he had to hire an attorney, overcome the temptation to settle, and persevere. Another charge was trumped up in England. Solzhenitsyn won but was thereby “drown[ed]. . .in trivia and filth.” No one broke into his home and stole his papers in the West; the courts could still resist elite opinion. Those are differences. The process was nevertheless a penalty. “I cannot think of the English legal system,” he writes, “without a sense of loathing.” But, he imagined, the court system could become more arbitrary and Soviet, someday, when elites captured more levers of power.

Telephones, Solzhenitsyn worries, integrate all into the borg of public opinion—and he finds it “absurd that people don’t want to recognize any space between them, any separation, any seclusion.” Such media rob people of independence and leisure at the same time, while strengthening the power of public opinion. The internet would aggravate that problem.

In Gulag, Solzhenitsyn imagines those who cross the threshold of evildoing without pangs of conscience. They have “left humanity behind, and without, perhaps, the possibility of return.” Such an ideological stance justifies lying to, ruining, and killing innocents. Those who cross that line leave behind the drama of good and evil in political life, putting forward new, superior morality. Under this new ideology, nations are passe and religion is bogus and tyrannical; our tolerance, as defined by the shifting demands of History, is our virtue. Western apparatchiks sold their souls to an ideology just as communists did—but without the cynicism and with the confident certainty that every word from their lips was blessed by history. Consciences are seared more in the West than in the East—that may explain Solzhenitsyn’s less than charitable treatment of Western pseudo-intellectuals.

Solzhenitsyn recognizes limits to this moral equivalence, of course. America is not evil to the core like the Soviet dragon. He had allies and admirers in the West (though he had them in the East too). For every dozen Mike Wallaces, there was a Malcolm Muggeridge; for every 50 conventional politicians, there was a Margaret Thatcher; for every pewful of shallow pastors or priests, there was a John Paul II. Greatness was possible in the system because, to paraphrase George Orwell, hope lay with the proles. Occasionally, the decent good sense that Solzhenitsyn recognized in his fellow citizens in Cavendish, Vermont could still find political expression on the level of the nation. Renewal was possible since many still knew how to govern themselves on the local level and people in the country could still rally themselves to act in the face of threats to its survival.

It is a great testament to Solzhenitsyn’s foresight that he saw Sovietizing perils for the West of his day, when it infected fewer institutions and less of life. The Western millstone has become its own Red Wheel in our late republic. Our freedom is still being ground down by our distinctive millstone. But perhaps there is still hope.