Military conscription is contrary to the self-direction that is necessary for a culture that holds liberty as paramount.

The Broken Road to Military Professionalism

For over three decades, the US military has been the envy of the world and has remained one of the most respected institutions in American society. While the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, combined with corruption and extremism in the ranks, have taken some of the luster away, it is remarkable how few citizens seriously question the role of the military in American society. In the rare moments when Americans do think about the military as an institution, they often perpetuate ahistorical and naive views that inhibit any useful discussion of the topic. Banal talking points such as “support the troops,” “these colors don’t run,” and “don’t use the military for social experiments” are examples of this uncritical approach.

In his ambitious new book, The United States Army and the Making of America: From Confederation to Empire, 1775-1903, Robert Wooster focuses on the development of the US Army as a social institution and attempts to answer two fundamental questions with contemporary implications―How did the United States military become the powerful, professional, and respected institution it is today and why did thinking about the role of the military in society change over time?

Wooster’s book is noteworthy because it succeeds in answering these broad questions on two distinct levels. First, it is a meticulous piece of scholarship that clearly traces a broad range of complex and evolving issues regarding US military policy. The narrative sweeps readers through US history and clearly demonstrates that military policy was a product of the political concerns of the moment. Issues such as the authorized strength of the Army, pay, pensions, the establishment of forts, roads and other infrastructure projects, the adoption of different weapons, and much more are all placed in their historical context. This allows readers to better understand how various pieces of the military establishment were created and how they evolved over time. If this were the only thing the book achieved, it would be noteworthy and worthwhile. However, the book is much more than a chronicle of US military policy.

On a deeper level, Wooster’s book is an examination of the fundamental debates regarding the role of the military in American society and the role of America in the world. In this much more complex and ambitious endeavor, this book also succeeds in making the past relevant and accessible for contemporary readers. The story that emerges is one of deep division between rival political factions, mistrust of government power, a mythos of the American founding that (mis)shaped policy, and a military that often failed to adapt to growing responsibilities.

Starting with the founding generation, this book develops the central theme that military policy was a direct reflection of the beliefs of politicians and political thinkers. Based on their experience with the British and their reading of history, the early patriots were particularly suspicious of standing armies, military professionals, and the taxation required to support them. The true threat to the young republic was not foreign enemies, but the threat from within. As James Madison, a proponent of a stronger central government, reasoned, “Constant apprehension of war…has the same tendency to render the head too large for the body…The means of defense agst. [sic] a Foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home…Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people.”

As a result, the framers of the Constitution (one third of whom were veterans) believed that local militias would be preferable to standing armies and purposely created checks and balances that made it difficult to build and maintain permanent armies unless there was a true consensus among all political factions and the three branches of government. In addition to the constraint on national armies, the framers also feared that individual states would amass dangerous levels of power, involve themselves in foreign entanglements, and perhaps even attack or threaten other states. Because of this, the Constitution prohibited states from levying standing armies or naval forces and from declaring war, a clear indication that the founding generation was deeply suspicious of professional militaries and unrestrained power.

When combined with the popular myth of the “minutemen,” these fears and the governmental structures they inspired led to military amateurism for decades to come. While European-style armies were necessary for winning independence, Wooster does an excellent job of tracing how the popular myth incorrectly credited militia forces with defeating the British. When combined with a suspicion of standing professional armies, this incorrect and populist view of the American Revolution had a profound impact on the military. While it is common today to assert that the military should not be politicized or used as a tool for social experiments, the more interesting fact is that the military has always been a highly politicized organization that was used as a tool to promote a wide range of political agendas.

This pattern of military politicization combined with a deep suspicion of military professionals and standing armies shaped the development of the American Army for the remainder of the 19th Century.

The Jeffersonians provide an illustrative example of the politicization of national defense leading to inconsistent policy. Philosophically, the Jeffersonians had opposed the creation of military forces as a threat to liberty. While in the political minority they had stuck to these principles and had consistently obstructed attempts from the Adams Administration to expand Federal power in general and military power in particular. However, once in office, the Jeffersonians used the spoils system to reward their supporters with military positions, used the military to explore and expand the frontier, founded the United States Military Academy at West Point to train and educate future generations of professional officers, and sent the Navy (which they had opposed funding) to conduct the first overseas raid in US history against the Barbary pirates. When given power and opportunity, the Jeffersonians could not resist the temptation to use the military for their own self-serving ends, philosophical ideals promoting limited government be dammed! Once out of power, the Jeffersonians suddenly became more ideologically pure and again opposed the use of military power and the maintenance of standing armies on the grounds that they led down the path to tyranny.

This pattern of military politicization combined with a deep suspicion of military professionals and standing armies shaped the development of the American Army for the remainder of the 19th Century. When viewed through this context, issues such as federalism, sectionalism, westward expansion, Native American relations, taxation, and debates over slavery take on new meaning. Indeed, according to Wooster’s interpretation, the inconsistent military policy of the young republic was due neither to neglect nor incompetence, but rather was a direct consequence of the Constitutional structure and the fractured political landscape. The fear that a standing army could be used by political rivals combined with the belief that citizen soldiers could effectively respond to the crises of the moment to ensure that there was never a sustainable political constituency for building and maintaining a professional force. As a result, the small cadre of military professionals were often unable to enact military reforms and American forces had an uneven record in combat because they were compelled to rely on unreliable militia forces and ad hoc volunteers.

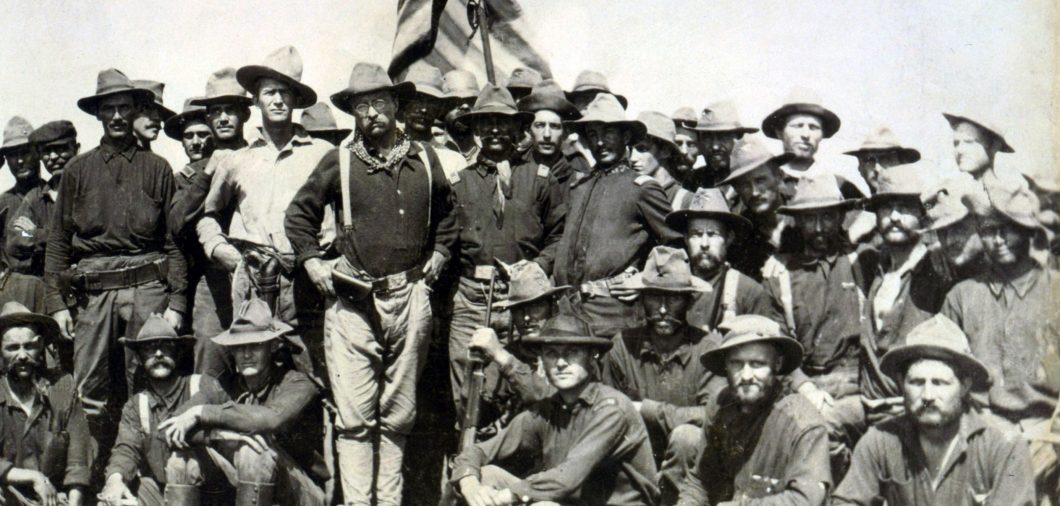

This pattern of amateur armies producing mixed results continued until the aftermath of the Spanish American War. The poor showing of American ground forces in this conflict and increased foreign commitments ultimately led to political consensus and a series of reforms in military training, equipment, doctrine, organization, and leadership. While the US Army would continue to struggle with professionalism, funding, and other civil-military relations for decades to come, it would eventually evolve into an institution that was less overtly politicized, increasingly professional, and more recognizable to contemporary audiences.

While students of the military, politics, and intellectual history will all find much to admire about this book, it is worth asking the obvious question―how does this book help us better understand the problems of our own time? Wooster does not explicitly say, and the answer to this question may be something of a Rorschach test for the reader. Indeed, it would be fair to view this book from a variety of perspectives including: a grand morality tale about the consequences of fractured politics; a critique of American exceptionalism; or a way to better understand the unique intellectual traditions in American political thought.

From the perspective of this reviewer, this book is extremely valuable because it reminds us of two simple truths―people are political beings and that ideas have far reaching consequences. Both of these ideas are so simple that it is easy to forget, yet these very questions are fundamental to being engaged and enlightened humans.

Viewed in this light, it is understandable that modern Americans politicize the military. We always have and always will. We are no less human than our forbearers. One can only hope (perhaps in vain) that by understanding how and why we got here that we can appreciate that the debates we engage in and the choices we make today will shape our warriors and the nation for many years to come.