The Forgotten Gifts of American Voluntarism

Over the course of the pandemic, many were cheered by the myriad ways in which people rallied to help their fellow citizens. But many protested—wasn’t this the government’s job? Shouldn’t the government supply PPE rather than relying on citizens to sew face masks, ensure that children didn’t go hungry, and to feed and house front-line medical staff? With much of this discussion shaped by the polarizing response to then-President Donald Trump, it is helpful to be reminded that the debate about the respective roles of the government and the citizens in responding to crisis goes back even before the country’s founding.

Elisabeth S. Clemens’ Civic Gifts: Voluntarism and the Making of the American Nation-State supplies this history. Dr. Clemens, who is the William Rainey Harper Distinguished Service Professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago and a specialist in the political development of the United States, takes an episodic approach by studying crises from the Boston Tea Party through the Great Depression and World War II. Her focus is on benevolent or charitable associations, which step in to meet welfare needs during crises. At issue is the proper balance among self-reliance, voluntary associations, and government to provide for citizens’ welfare. Dr. Clemens sees an “unexpected prevalence of charity and benevolence” from both government and voluntary associations. “The puzzle,” she writes, “is to understand how charity and the gift became central elements in a purportedly liberal and individualistic political culture.”

Conservative readers who believe widespread charity and a robust civil society are spontaneous components of a healthy liberal democracy may be less puzzled about how charity and individualism go hand-in-hand. This quibble aside, there is much to appreciate in this important history of voluntary associations and their relationship to government. Particularly noteworthy is Dr. Clemens’ attention to the power of ideas to shape action, evidenced by her frequent quotations from speeches, correspondence, and papers of the men and women who led or opposed various associations and benevolent initiatives. Dr. Clemens challenges what she sees as a too-simple narrative of Americans as inveterate founders and joiners of associations, a narrative she attributes to “a stylized summary of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.” She presents a history of voluntary associations that is complicated and contested (and she points out Tocqueville’s own account of associations is more nuanced than is often supposed).

As Dr. Clemens explains, voluntary benevolent associations were essential to the very founding of the United States. When the British blockaded the port of Boston in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party, “communities throughout the colonies contributed sheep, cattle, barrels of rice, and the occasional pipe of brandy to the Boston Committee on Donations” to sustain the Bostonians, who “were understood to be suffering for a nation or polity that had not yet been formally declared.”

But while support for the Boston Committee on Donations helped to write a “story of peoplehood” and paved the way to the Founding, Dr. Clemens writes that this did not translate into unqualified support for voluntary associations among the Founders and early civic leaders. Dr. Clemens quotes Noah Webster’s statement that voluntary associations were “useful in pulling down bad governments; but…dangerous to good government;” Thomas Jefferson’s view that “permitting the spread of voluntary associations and corporations would threaten equality by allowing a small minority, a cabal, to exercise disproportionate influence over public life,” and George Washington’s objections to “the promiscuous mixing of mutual benevolence and state- and national-level political didacticism.”

Of course, these same men led voluntary associations. Webster, for example, founded the Connecticut Society for the Abolition of Slavery and Washington was the first president general of the Society of the Cincinnati. But Dr. Clemens surprises readers who supposed early American leaders were unambiguously supportive of associations as civic institutions by describing their worry that associations could be vehicles for factions. Voluntary associations had an important role, but not as organizations dispensing charity in place of government. Washington, for example, arranged for the charitable funds of the Society of the Cincinnati to be turned over to and dispensed by state legislatures to avoid citizens’ dependence on a private association.

Dr. Clemens writes that, by the Civil War, three competing visions about the relationship between benevolent voluntary associations and government had emerged. One vision kept alive the views of Washington, Jefferson, and Webster, that there should be no “promiscuous mixing” of these associations with government functions. Dr. Clemens cites Samuel Gridley Howe, a physician and member of the United States Sanitary Commission. The commission was founded during the Civil War to advise the U.S. Army’s medical corps, but became a vehicle for channeling citizens’ donations to Union soldiers. Howe eventually resigned, writing “it would be a misdirection of public charity to do what the Government can do, and ought to do, and will do.” This vision emphasized self-reliance, but when it came to providing for soldiers, their widows, or the worthy poor, it is government that should meet these needs, not charities.

Another vision championed these associations as a popular check on the power of government. This vision sought to replicate the success of the Boston Committee of Donations through broad citizen contributions to support (and thereby influence) government and civic causes, and to build a sense that the nation was striving to meet shared aims. During the Civil War, this view was exemplified by the exact organizations that Howe found so objectionable: the United States Sanitary Commission and its peer the United States Christian Commission. Dr. Clemens quotes one observer: “the Sanitary and Christian Commissions, in their ultimate results, are to make the armies of the world the armies of the people and not of kings.”

A final vision agreed on the importance of associations supporting government and civic causes, but distrusted populism. This was the vision of business and social elites, who wanted to ensure voluntary associations “bypassed both the strict constraints of electoral democracy and the dangerous powers of a centralized bureaucratic state.” During the Civil War, this vision was exemplified by organizations in major cities such as “the elite-dominated [New York] Union Defense Committee [which] raised volunteer regiments, collected funds to support soldiers’ wives and families, and eventually took charge of public funds to support their voluntary effort.”

Despite being a major force in American civil life from the Boston Committee on Donations through the first quarter of the 20th century, popular benevolent associations are nearly absent today.

While the first vision opposed any mixing of charities and government, the other two embraced this mixing but were at sharp odds about whether popular or elite sensibilities should lead. Dr. Clemens tells how the tensions between the latter two visions led to blows between Ernest Bicknell, who embodied elite-led benevolence at the turn of the 20th Century as secretary of the Chicago Bureau of Associated Charities, and Father Basil, a Catholic priest. Frustrated by the Bureau’s denials of his request for support for a home for boys, Father Basil went to the Bureau’s offices and gave a beating to Ernest Bicknell. Father Basil had stopped by a courthouse on his way and been advised that the fine for assault ranged from three to one hundred dollars—apparently a price was worth paying to deliver a message to the elites that they should harken to those actually working and living among the poor.

Dr. Clemens describes how each of these three visions had their champions and critics during the Civil War, depressions of 1873 and 1893, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, World War I, and the Mississippi Flood of 1927. Leading players appear repeatedly: Ernest Bicknell survived his encounter with Father Basil to go to San Francisco in the wake of the earthquake—uninvited by local authorities but at the direction of several Illinois organizations—and would later become first national director of the Red Cross. Over the decades, these three visions were realized in new forms. Community Chests, for example, became favored vehicles for elite philanthropy, while Block-Aid—which introduced the first “call this number now” appeals—became a vehicle for popular support of government relief efforts.

The Great Depression fundamentally reset this contest as the economic crisis overwhelmed the ability of citizens and voluntary associations. Instead, the government took primary responsibility for providing for citizens’ welfare. However, even during the Depression, voluntary associations still enjoyed support in many quarters. Franklin Delano Roosevelt himself championed the March of Dimes, then known as the Committee to Celebrate the President’s Birthday, to raise funds for polio research and treatment. In short, each vision persisted, even as the balance shifted inexorably away from citizen self-reliance to voluntary associations entwined with government and to government itself.

Dr. Clemens’ account of these episodes and how different visions informed the balance of citizen self-reliance, voluntary associations, and government in response to those crises is a valuable history; it provides us a new framework in which to take stock of the health of American voluntary associations and civic life during our current pandemic crisis. To do so, we may ask how—if at all—her three visions remain present today.

The vision most conspicuous today is of elite-led voluntary associations working in concert with government. For example, during the Obama Administration, as Megan E. Tompkins-Strange detailed, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, and other elite philanthropies played a major role in reshaping education policy (so much so that an Obama-era Department of Education official once referred to the “Obama Administration” as the “Gates Administration”). During the pandemic, celebrity chef José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen exemplifies a new kind of elite-led voluntary association that works in concert with government: FEMA subsidized WCK to provide food in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, and during the pandemic, state and local governments are using FEMA funds to provide meals from WCK.

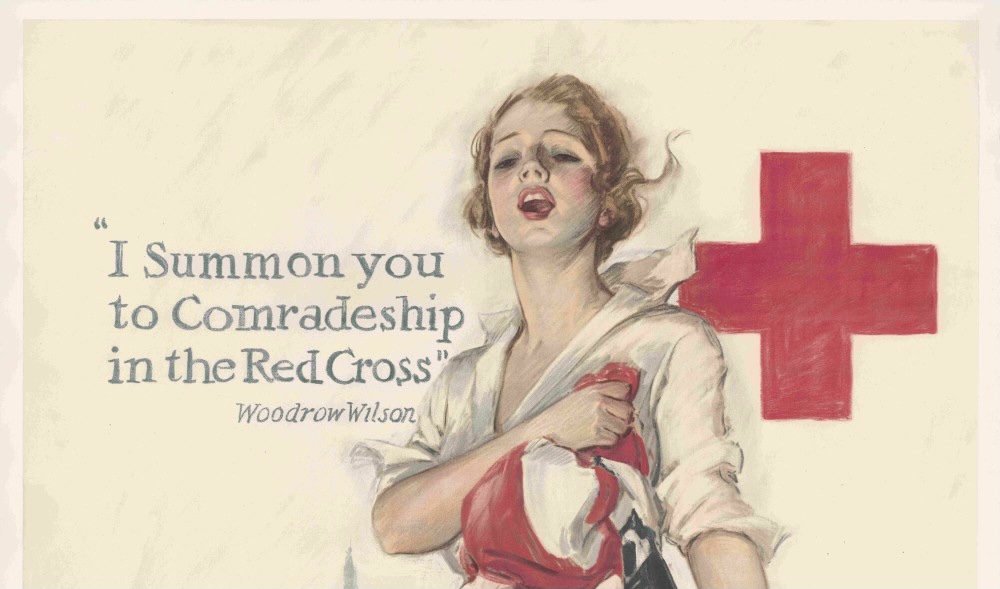

Despite being a major force in American civil life from the Boston Committee on Donations through the first quarter of the 20th century, popular benevolent associations are nearly absent today. Dr. Clemens notes that “by December 1917, 22 percent of the American population had made a least the basic contribution that signified membership in the organization” to support the American effort in World War I. Today, Americans are so fragmented and polarized that no organization has the trust of so many. To be sure, Americans give more generously than ever: during 2020, giving rose 11%, and small donors, whose gifts had fallen off in recent years, contributed to that boost. Indeed, there may be reasons to favor smaller, local associations over a national association such as the Red Cross; but the fact that it is difficult to imagine so many coming together to support a single organization testifies to a lost sense that we can rally to face together national challenges. Dr. Clemens book, completed shortly before the pandemic, ends with a nostalgic hope that Americans could recover the possibility of mobilizing in a crisis through voluntary associations, acting as “democratic citizens [who] insisted that government depended not only on popular consent but popular contribution.” The events of the fifteen months have shown just how difficult it would be to realize that hope.

Dr. Clemens’ excellent study helps us understand the visions and practices of voluntary benevolent associations throughout America’s history—and provides a vantage point for assessing the erosion of our feelings of solidarity and common purpose with our fellow citizens.