If history teaches us anything, it is that acting like “everything is up for grabs” is precisely what produces reigns of terror.

The Heroic in France

Scarcely a day goes by without some historical figure once seen as “great” being toppled from their pedestal. Nobody, it seems, is immune from being cut down to size. Those most celebrated for their deeds are judged instead by their words, even words unknown to their contemporaries—and judged, moreover, by the moral sensibilities of the present rather than the past. The higher they had once been held in our forebears’ esteem, the further they must now fall. Hamlet’s wise admonition—“Use every man after his desert, and who shall ’scape whipping?”—has been consigned to oblivion.

Yet many of us who live in a post-heroic age are nostalgic for a more innocent time when heroes were recognised as such and given their due. The classic text is Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (1841). Today, to cite Carlyle except as an example of racism or proto-fascism is to court opprobrium; even his Chelsea home which was preserved as a museum to the historian and his literary wife Jane—a unique Victorian time capsule—is now closed indefinitely. Yet Carlyle had something important to say about the heroic and its antithesis, which he called “valetism”—a homage to Hegel, from whose Philosophy of History he had learned about “world-historical individuals.” There, Hegel cited his own Phenomenology of Spirit—“no man is a hero to his valet, not because he is not a hero, but because the valet is a valet”—adding proudly that this aphorism had been quoted by Goethe. Were Hegel and Carlyle alive today, they might wonder whether our culture had been usurped by valetists: those who judge genius and especially its flaws from the servile standpoint of the Kammerdiener.

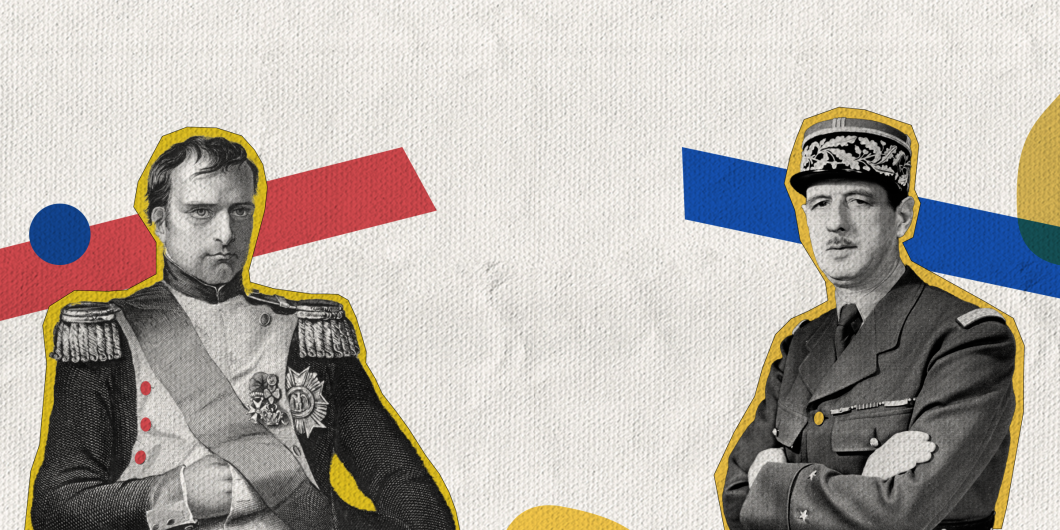

Patrice Gueniffey certainly does not subscribe to historical iconoclasm, which has not yet prevailed in his native France as completely as in the English-speaking world. One might deduce as much from his monumental biography of Napoleon, the second volume of which is eagerly awaited by admirers of the Emperor in this, his bicentenary year. Yet his much shorter recent study, Napoleon and de Gaulle, is more explicitly intended as a vindication of the impact of the individual on history. In its original language, the subtitle was Deux héros français. For an Anglophone readership, the Belknap Press has altered “two French heroes” to Heroes and History—an unmistakable allusion to Carlyle’s “the Heroic in History.”

With this superbly written and elegantly translated essay in comparative portraiture, the author has thrown down the gauntlet to the dominant schools of contemporary historiography, all of which emphasize impersonal factors, whether economic or social, geographical or climatological. Gueniffey unabashedly believes in the power of rare individuals—“heroes”—to alter the course of events. Indeed, he hardly dissents from Carlyle’s view that great men and women are the sole cause of human progress.

On Heroes

It is no accident that Carlyle belonged to the generation that grew up in Napoleon’s shadow, deeply influenced by German thinkers who, like Hegel, had glimpsed “the world spirit on horseback” or even, like Goethe, conversed with him. At 65, Gueniffey is old enough to have lived through de Gaulle’s comeback, his creation of the Fifth Republic, his fall, and especially his death. Tout le monde attended the General’s requiem in Notre Dame, which cannot have failed to awe an impressionable teenager. What Napoleon was to Carlyle, de Gaulle is to Gueniffey. Yet just as Carlyle wrote a huge life of Frederick the Great but never one of his near contemporary Napoleon, so Gueniffey has devoted his life to Napoleon but never, until now, written about de Gaulle.

However, recent years have seen outstanding biographies of Napoleon and de Gaulle by the British historians Andrew Roberts and Julian Jackson respectively. Though neither writes in Carlyle’s heroic mode, both are fascinated by the cults that surround these great men—as, of course, is Gueniffey. Roberts even entitled the British edition of his book Napoleon the Great, though this was changed for the American readership to the blander Napoleon: A Life. Gueniffey’s study of the two heroes came out in 2017, so he was unable to take account of Jackson’s work, which also had a revealing title: A Certain Idea of France—de Gaulle’s self-description of his distinctive kind of patriotism. The awe in which these two figures are still held—uniquely among French leaders, as Gueniffey informs us on the basis of opinion polls—even extends far beyond their own patrie. Both were seen at the time as saviours in adversity and unifiers in division. Now they each stand out for their “grandeur”—a quality that Gueniffey finds manifested as much in their lives as in their achievements, in words no less than deeds.

“If Napoleon was the least French of Frenchmen, de Gaulle was, on the contrary, the most French of Frenchmen.”

Patrice Gueniffey

In both cases, there is a moment when their heroic qualities and status among their compatriots suddenly emerges. For Napoleon, it comes during the siege of Toulon in 1796, when the young commander first displays that instinctive strategic grasp and tactical coup d’oeil which, within a few years, would propel him to heights of military glory not seen since Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. Once the British naval squadron has been driven off by his artillery, the royalist stronghold falls into his hands like a ripe fruit. Seemingly effortless in his ability to inspire loyalty, the young Bonaparte’s charisma carries his armies across Europe and beyond. His own heroism makes heroes of his troops, however many of them he sacrifices for an empire that exists solely as a stage for its creator. In a meteoric career that lasted barely 20 years, Napoleon makes himself lawgiver, liberator, and legend. There has been nothing like it before or since.

For de Gaulle, that heroic moment comes much later in life, at an age when Bonaparte was already dead. A relatively junior general, his only chance of action against the German invaders is barely more than a footnote in the fall of France in May 1940. Only when the panzer divisions have already broken through does de Gaulle, commanding an armoured counter-attack, show what he is made of. It is too little and too late. In the memoirs of his opponent, Guderian, the German writes: “The danger from this [left] flank was slight…During the next few days de Gaulle stayed with us and on the 19th [of May] a few of his tanks succeeded in penetrating to within a mile of my advanced headquarters…I passed a few uncomfortable hours until the threatening visitors moved off in another direction.” That was all that de Gaulle could do—but it was enough. Despite superiority in numbers and equipment, no other French commander achieved even so much, in what the historian Marc Bloch called “the strange defeat”.

Briefly co-opted into the Cabinet by his friend Paul Reynaud, he is ousted by the new regime of Marshal Pétain, who sues for peace. Unbowed but still unknown, he crosses the Channel and, with no authority but his own sense of destiny, issues his immortal Appeal of 18 June on the BBC: “Moi, Général de Gaulle, actuellement à Londres…”

Frenchmen?

Just as Churchill rallied the British at about the same time and as Roosevelt would do after Pearl Harbor, de Gaulle’s appeal made him the conscience of France in her darkest hour. Amid chaos and humiliation, the French heard a voice of hope, telling them that their duty was to join him and la France Libre, the Free French, in London if possible, to resist at home if not. The battle of France was over, but the war was not: “This is a world war.” This global conflict was a God-sent opportunity. The world would empower the liberation and he would lead French soldiers into Paris. De Gaulle’s form of heroism was thenceforth always about France.

Napoleon, by contrast, saw France only as a springboard for global conquest. As Gueniffey puts it: “In sum, if Napoleon was the least French of Frenchmen, de Gaulle was, on the contrary, the most French of Frenchmen.” The Revolution was all about humanity as a whole and the armies who fought under Bonaparte’s banner were as heterogeneous as the Empire he created. Though he adopted Charlemagne’s gesture of a coronation by the Pope in Rome, the parvenu Emperor placed the crown on his own head in Paris. There was nothing Christian about Napoleon—all his symbolism was classical. Like the Romans, his legions brought glory and civilisation, but at the point of a bayonet. His cavalry reduced Cologne Cathedral to a stable.

Lacking military force, de Gaulle mobilised spiritual and moral energies in his crusade against the godless Nazis. A devout Catholic, he challenged the collaboration of the clergy under Vichy France. As the symbol of the Free French, de Gaulle adopted the Cross of Lorraine, the precarious province wrested back from the Germans after 1918 but restored to the Reich by Hitler. When the General prophesied victory, he was believed. In 1934, he had warned Pétain and other military grandees of the threat from a new kind of mechanised warfare. The prophecy had come to pass, the prophet had been vindicated and the French followed him.

But only for as long as it suited them. While the war lasted, the prophet-general had no need of policies because he embodied them. On the greatest day of his life, the liberation of Paris on 25 August, 1944, he strode alone along the Champs Élysée past the rapturous multitudes. At l’Hotel de Ville, he gave them his manifesto in three words: “La guerre, l’unité et la grandeur, voilà notre programme.” Yet only a year after the German surrender, de Gaulle had resigned. Without war, it seemed, there was no unity and no grandeur either. He tried to start a new movement. When it failed to sweep him back into power, he retreated to his home at Colombey-les-Deux-Églises in northeastern France. Only a decade later did he return to rescue France again, this time from the threat of a military coup mounted by the army in Algeria. Only the war hero could save the nation from civil war. The price of his comeback was a new Republic, the fifth since 1789, created in the image of the General himself.

Had it not been for the shock and disillusionment of les évenements in May 1968, would the founding father of the Fifth Republic ever have relinquished power voluntarily?

This last phase of de Gaulle’s career has left its mark on France, but his legacy has been a mixed blessing. Just as Napoleon’s transformation of a revolutionary republic into an imperial monarchy turned France into a despotism and placed an intolerable burden on the Emperor, so de Gaulle’s combination of an elective presidency and a parliamentary system, with only a weak separation of powers, has shone an unforgiving light on the lesser men who have succeeded him. Napoleon was, Gueniffey reminds us, at first compared to Washington as the victor of a revolutionary war; but while the American refused the crown, the Frenchman seized it—and, even after his abdication, returned from exile to reclaim it.

All the same, both Napoleon and de Gaulle are rare in having even attempted comebacks. If the Hundred Days was always likely to end in defeat, it was at least the most spectacular one in history—indeed, we still say of leaders that they have “met their Waterloo.” As for de Gaulle, after his equally dramatic resurrection from the politically dead in 1958, he enjoyed a decade of almost untrammelled authority in which to shape his country. Raymond Aron, great liberal-conservative intellectual of the day, had warned of the General’s dictatorial tendencies, both during the war and again on the eve of his return in 1958. But Aron later admitted that he had been wrong to fear “the shadow of the Bonapartes”: de Gaulle was “a charismatic leader par excellence” but he resembled Washington more than Napoleon. Aron was perhaps too generous to the General. Had it not been for the shock and disillusionment of les évenements in May 1968, would the founding father of the Fifth Republic ever have relinquished power voluntarily?

From what might have been a mere jeu d’esprit, Gueniffey has conjured a beautiful and profound reflection on the meanings of heroism. He shows how his compatriots transformed Bonaparte into a mythical conqueror of Roman nobility, while de Gaulle has been transfigured into a chivalric legend from the Chanson de Roland. Unfortunately, in the four years since it appeared, the eclipse of such values has become almost total. Napoleon’s bicentenary is being overshadowed by the cancel culture, which focuses on his attempt to reintroduce slavery in the French colonies, to the exclusion of everything else.

The mantle of De Gaulle has been donned by Emmanuel Macron, who nevertheless disdains almost everything that made the General unique, except his aversion to “les Anglo-Saxons.” Yet it was Churchill, that quintessential Anglo-Saxon statesman, who showed a true instinct for the heroic theme in French history. It was he who extended every assistance to de Gaulle in wartime, despite the latter’s intransigence that provoked his notorious remark that “the hardest cross I have to bear is the Cross of Lorraine.” When de Gaulle showed him the tomb of Napoleon in Les Invalides soon after the liberation of Paris, Churchill bowed his head and declared: “In the world there is nothing grander.” Thanks to Gueniffey, we too have been reminded that, for all the flaws of these heroes, humanity would be the poorer without the example of their grandeur.

Editor’s Note: This review has been updated to clarify the location of Napoleon’s coronation.