Confronted with the fragility of human life, Walt Whitman did not turn his back but looked it directly in the eye.

The Past Is Never Dead

“I don’t think there’s really a lot of research left to do: Those specialists and aficionados have documented his life damn near day by day.” So said John Shelton Reed when I asked him, during a 2012 interview, whether there was more to learn about William Faulkner’s life in New Orleans.

Reed may have been right, not just about Faulkner’s life in New Orleans but about his life, period. That would explain why Michael Gorra’s story about Faulkner is just that: a story, not a biography or, strictly speaking, a work of scholarship. And it’s a story—nonfiction, of course, but part memoir and part history and historiography—that involves theories of time, of the pastness of the present and of the presence of the past, examining the relationship of the Civil War to Faulkner and his fiction.

Reading The Saddest Words during a disorienting phase of mandatory lockdowns and widespread quarantines only intensifies its emphasis on suspended time, on moving forward by looking backward, or backward by looking forward, especially in the wake of a presidential election that occasioned dire warnings of a second Civil War.

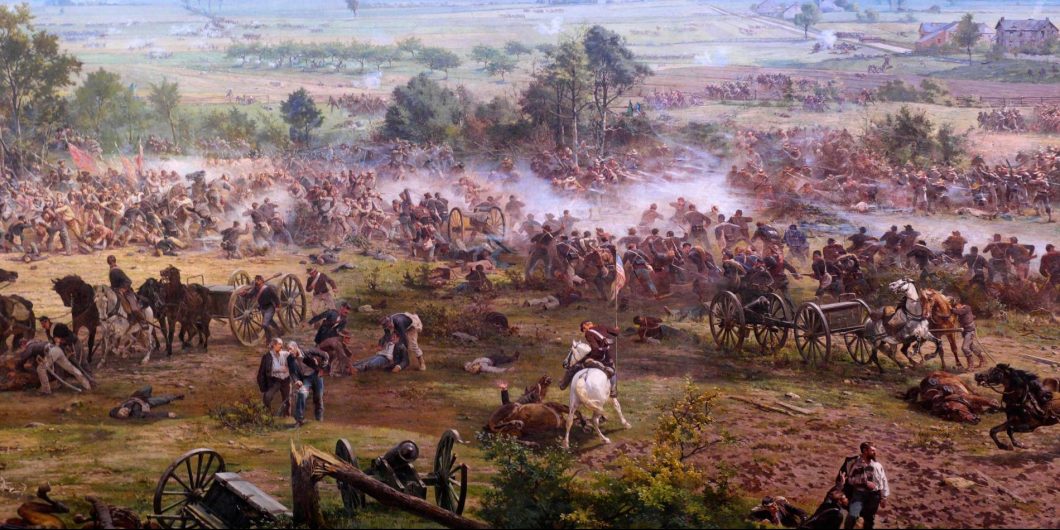

“Great fiction about the Civil War will never be about just the war itself, in the sense of battles and campaigns,” writes Gorra. “The real war lies not only in the physical combat, but also in the war after the war, the war over its memory and meaning.” The first-person “I” with which Gorra guides us through battlefields, New Orleans, Richmond, Natchez and Oxford, Mississippi, among others, reminds us that the Civil War is, in a sense, ongoing, a narrative without end. Sharing his 21st century experience of Faulkner’s 20th century experience of the 19th century Civil War—of memories of memories of memories—Gorra multiplies the complexity of the already complicated feeling that we’re always still fighting, that the hostilities aren’t over even if the physical violence has, mostly, taken the form of rhetoric and discourse. Mostly.

Faulkner was born in 1897, over 32 years after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Faulkner’s South was, in Gorra’s words, “a land where the dead past walks, not was but is, and burning always in one’s mind.”

Was. That verb and again are the two “saddest words” captured in the book’s title. They’re drawn from The Sound and the Fury, more specifically from the characters Jason and Quentin Compson, the latter of whom determines, in a suicidal state, that “again” is the sadder term (because it involves inescapable recurrence, relapse, or repetition).

Faulkner didn’t write much about the Civil War, truly. At least not as a live event or as dramatized action. He focused, rather, on the before and after, the slaves and the soldiers hauntingly present in their palpable absence. Nor was he after moonlight-and-magnolias nostalgia. His Yoknapatawpha was the site of murder, rape, and incest—of the dark and sordid secrets that Southerners hoped to bury. His plots—orderly disordered or disorderedly ordered—are neither chronological nor linear. Marked by analepsis and prolepsis, they transport you through time, sometimes alternating narrators, with repeated attention to the same families and figures.

And to race, about which Faulkner’s track record is mixed. “Faulkner used racial epithets almost every day of his life,” Gorra says, “and as a young man he accepted the whole social order of the Jim Crow South.” Faulkner was in this respect like nearly every other white man alive and residing in Mississippi during that era, “caught by the conventional thought and language of his time and station.” Fiction, however, freed him from those inevitable confines. “The pen made him honest, and from the beginning he skinned his eyes at the racial hierarchy in which a part of him never stopped believing.”

Discussions of race today too often lack nuance, characterized as they are by bad-faith soundbites, slogans, hyperbole, denunciations, and memes; the weaponization of figures and events to destroy or discredit rivaling perspectives and opinions; and the unwillingness to address or acknowledge significant tensions, contradictions, circumstances, and contexts. In such a toxic climate, how does one read Faulkner? How does one analyze his rendering of the racism that was embedded in the laws and institutions of Southern states, counties, and cities, that shaped everyday attitudes about whites towards blacks and blacks towards whites?

Very carefully.

Not surprisingly, then, Gorra’s measured meditations strain to avoid condemnation. To those who refuse to read Faulkner at all because of his views on race, Gorra passes no judgment, stating, “Such decisions are personal and not perhaps subject to argument or exhortation.” Gorra, for his part, purports to read Faulkner because of the writer’s struggle, against the weight of history and culture, to convey truth through literary invention, a medium through which truth could permissibly pass. Faulkner is “difficult,” Gorra insists, and his “books [are] better than the man.”

These days, writing favorably about a Southern white male from the early 20th century—and about his views of the Civil War no less—is understandably risky, requiring vigorous intellectual distancing to avoid backlash and cancel culture. Gorra makes it clear where he stands not only on Faulkner and Southern history, however, but also on current events that seem to fall outside the scope of his chosen subject. Gorra’s assessment of Faulkner goes far beyond Faulkner, from and against whom he extrapolates political ideas about current culture.

In his introduction, for instance, he recounts contemporary politics, claiming that the Tea Party’s “cadres” invoked nullification, which he thought “was a dead letter, a belief that had vanished even before the Civil War.” If this sounds smug or dismissive, it’s also erroneous. Apparently, Gorra overlooked recent efforts at marijuana legalization by states in contravention of federal law. He missed, as well, the attempt of so-called “sanctuary cities” to circumvent federal immigration laws.

You can argue whether these local acts of defiance—which don’t seem to reflect residual aggression left over from the Civil War—constitute formal, official nullification. Regardless, Gorra implies here that nullification is an automatic, intrinsic bad. Would he take issue, however, with those Northern states that, prior to the Civil War, enacted “Personal Liberty Laws” to protect former slaves from the harshness of the Fugitive Slave Act? Surely not. Let’s not forget, moreover, that the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions—the best-known expression of nullification—targeted the horrible Alien and Sedition Acts. Surely Gorra doesn’t think the Alien and Sedition Acts were ideal or excellent enactments.

Gorra opines elsewhere that “[t]here may be political or practical questions about the removal of Confederate monuments. There are no moral ones.” None? Not one? What of the argument that removing these monuments deprives viewers of the opportunity to learn moral lessons, namely about the period in which most of these monuments were erected (decades after the Civil War)?

The days when Southern white boys grew up valorizing Confederate generals and romanticizing Civil War battles and campaigns, invoking myths of the Lost Cause, uttering to themselves “what if” or “if only,” are long gone.

One who beholds a statue naturally wonders why and how it got there to begin with. Consequently, Confederate monuments force passersby to recall problematic, shameful elements of the past, to question how white supremacy could have been so acceptable and widespread. Such intellectual labor wouldn’t occur if the monuments were out-of-sight, out-of-mind. You don’t have to buy this argument (and, for the record, I don’t, at least not fully) to recognize that it’s a moral one. Gorra himself seems to favor the “series of skeptical contextualizing plaques [that] have been placed next to the [University of Mississippi’s] Confederate monuments, with other tablets to document the labor of the slaves once owned by the university itself.” So does he or doesn’t he prefer the outright removal of Confederate monuments? I’d chalk this equivocation up to hypersensitivity regarding a hypersensitive issue.

Gorra’s message for anticipated (leftist) audiences is, at any rate, that Faulkner isn’t so bad after all, that this conflicted Mississippian often but not always overcame the circumstances of his birth and the sad constraints of his moment and place to author difficult texts that struggled with the brutal legacies of slavery. That won’t satisfy uncompromising, woke zealots, but it resonates with those who are reasonable enough to appreciate that everyone will be measured by future standards that the living cannot meet or understand. We must forgive to be forgiven, placing clarity and understanding before victory and conquest.

Gorra means well and goes about his business in good faith. His prolixity is charming rather than irritating, chiefly because it lacks the jargon and esoterica that have afflicted too much writing coming out of English departments. He’s got an ear for language and a knack for diction. But readers unfamiliar with Faulkner’s novels may feel tempted to skip beyond his plot summaries and analyses, however deftly they’re presented.

The days when Southern white boys grew up valorizing Confederate generals and romanticizing Civil War battles and campaigns, invoking myths of the Lost Cause, uttering to themselves “what if” or “if only,” are long gone. If anything, they ask “what for?” or “why?” Most likely they don’t care at all.

To those who police such standards, Faulkner should, then, be “safer” to teach and read than ever before. The failure to teach and read him might just make matters worse. For Faulkner—both the man and his writing—supplies clarifying context for contemplating questions about race relations that we ask again and again, eluding definitive answers, slowly healing, never forgetting.