David Brooks calls himself an American Whig, but there are good reasons a Whig restoration is impossible.

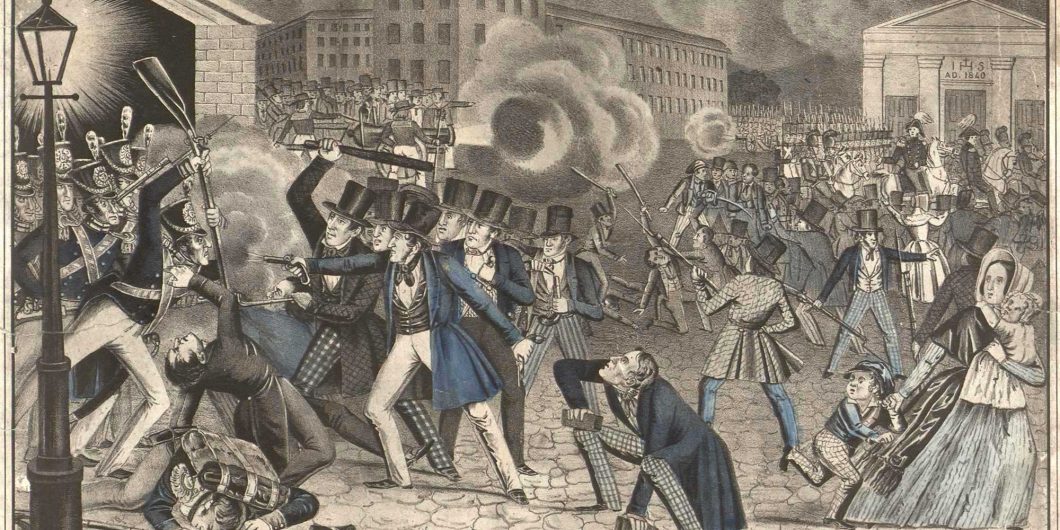

The Philadelphia Bible Riots

Mobs don’t think, as the adage goes, but they have often substituted for thinking by playing a leading role in fomenting political disagreements and deciding political questions.

Mobs fill vacuums. They arise and pose a threat in multiple circumstances: when government is weak or ineffective; where government actively participates in actions that a large proportion of the population perceives to be unjust; and when mobs and governments join forces to assault an out-of-favor group. American history is replete with examples of each.

In May and July 1844, the streets of Philadelphia were witness to combinations of these circumstances to deadly effect. In The Fires of Philadelphia: Citizen-Soldiers, Nativists, and the 1844 Riots Over the Soul of a Nation, George Mason University history professor Zachary M. Schrag offers a meticulously detailed blow-by-blow account of how a dispute ostensibly over Bibles in public schools inspired deadly rage.

Although the tinder that sparked the so-called Bible Riots was—as is so often the case—alleged concern about “the children,” the debate regarding which Bible kids should read in school was actually a proxy for a more insidious divide in which “nativists” strove to deprive new Catholic immigrants of the full rights of citizenship.

The “nativists” of the subtitle is unfortunate. Although the perpetrators often referred to themselves this way, they were in fact much more anti-Catholic than anti-foreign. Some Protestant Irish immigrants lined up with the so-called nativists. Almost all the rhetoric was sectarian. And Schrag admits as much, even as he persists in using “nativist” to describe the Protestant side. “Calling opponents of immigration ‘nativists’ may give too much credit to their own branding,” he writes. “As a Catholic newspaper explained, ‘There is no disguising the fact at this moment, that the soul, and animus, of the Native American party is hostility to the Catholic citizens, whether of native or foreign birth.”

The Protestant Whig ascendancy was doing what all ascendencies do—protecting their ascendancy, and the political and economic privileges that go along with it. As Catholic immigrants poured into America over the following decade, the anti-Catholic vitriol would grow more hostile and more organized.

Among Philadelphia’s most vitriolic was the central character in Schrag’s tale: newspaper editor Lewis Levin, editor of the Philadelphia Daily Sun. In another time and place, Levin, a Jewish convert to a vague sort of Protestant Christianity, might have been a candidate to lead a crusade in support of religious toleration. But as it was, Levin’s journalism left no doubt that the target was not foreigners in general, but the Papists who had left a trail of “blood-prints; human victims; civil wars; tortures; burnings; fire; desolation” wherever they wielded political power. Levin was determined they would not wield that power in Philadelphia.

The early anti-Catholic movement involved Democrats as well as Whigs and the loosely affiliated. And it quickly morphed into a movement separate from either party as local blocs in New York, Philadelphia, and other cities formed parties of their own.

Modern psychologists might see a case of projection in the political anti-Catholicism of mid-19th century America. For all the fears expressed by Protestants about the potential for theocratic rule under the Pope, it was the Whig Party that was insistent on imposing its version of right and wrong on the people—for their own good, of course. Whigs populated and paid for the Benevolent Empire of activist organizations that promoted religious teaching and sought reform on a variety of issues from abolition to education to temperance, and the party was happy to enlist government in their cause. The 1844 Whig vice-presidential candidate, Theodore Frelinghuysen, was a leader in many of those organizations. John Quincy Adams complained of the “pernicious factious influence of these Irish Catholics over the elections in all the populous cities.” And, as big-city Democrats increasingly courted the wave of Irish immigrants, it was the remnants of the Whig Party that eventually joined forces with the nativist parties (particularly the American Party, or Know Nothings) to form the core of the new Republican Party a decade later.

As Hillsdale College history professor Miles Smith IV recently put it, “A lot of the anti-Catholic sentiment ca 1845 in the US . . . can be reduced to ‘you’re better at getting your people to the polls than we are, and we’re mad about it.’”

Of course, the “nativists” argued that they were only trying to practice the free-speech rights guaranteed by the Constitution. When they rallied in Philadelphia’s Catholic neighborhood of Kensington in May 1844—something akin to Orangemen marching through the Falls Road section of Belfast on the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne—rowdy residents shouted them down. One even literally called BS on the rally, dumping a load at the base of a jerry-rigged speaker’s stand.

Neither side was particularly respectful of the rights of assembly or speech. But such claims of victimization aside, the Protestant majority was almost always the aggressor in these clashes. That this happened in Philadelphia, a city founded on the notion of religious toleration, only added to the sense that the country was in the throes of a dangerous division over the rights of religious minorities.

“To men like Levin,” writes Schrag, “the Irish Catholic community represented a unique threat: a community large, homogenous, and organized enough to change the character of Philadelphia” and, perhaps, the country.

The question—in 1844 as it remains today—is whether the authority of the state will be employed to quell the mob or to augment it. The former is the foundation of ordered liberty. The latter is something else entirely.

That description applied elsewhere. There were two separate uprisings in Philadelphia in 1844, in May and July. In June, almost 1,000 miles to the west, there was another.

A mob aided and abetted by civil authorities murdered Mormon prophet Joseph Smith and effectively ejected the Mormons from their home in Nauvoo, Illinois, along the Mississippi River. Something similar had happened six years earlier in Missouri, when local militias attacked Mormon settlers and the governor issued an infamous “extermination order” intended to drive the saints from the state.

And here is where the summer of ’44 mobs diverge. In Philadelphia, after some stops and starts, the civil authority in the form of local militias defended order. A few companies hesitated to fire on their neighbors and exhibited sympathy with the anti-Catholic mobbers, but, in the final analysis, they did their duty and dispersed the mob. In Illinois, the civil authorities sided with the mob. Philadelphia’s Catholics survived. Nauvoo’s Mormons, having seen their government abandon them to the mob, fled.

Six years earlier in Springfield, a mere 130 miles from Nauvoo, a young Whig lawyer had warned that “if the laws be continually despised and disregarded, if their rights to be secure in their persons and property, are held by no better tenure than the caprice of a mob, the alienation of their affections from the government is the natural consequence; and to that, sooner or later, it must come.” As would so often be the case, Abraham Lincoln was prophetic.

The Dogma Lives

When Philadelphia’s Protestants disregarded the rights of their Catholic neighbors to be secure in their persons and property, they confirmed what many of those neighbors already suspected.

Catholic fears of Protestants using public schools to convert their children were not unfounded in the middle of the 19th century.

There were multiple cases of Catholic children being punished for reading from Catholic Bibles, and even so-called compromises typically ended to those children’s disadvantage—Catholic students might not be required to read from Protestant Bibles or sit for Protestant instruction, but they were required to leave the room while the Protestant kids had their lessons. As Schrag puts it: “Protestants and Catholics agreed that schoolchildren should read the Bible, yet disagreed about what a Bible was.”

Here Schrag makes an unforced error, writing that “officials struggled to reconcile the public’s wish for moral instruction with the constitutional mandate to separate church and state.” There is no such mandate, and it wouldn’t be until the second half of the 20th century that the Supreme Court began to impose such a separation on school children. But the majority’s insistence on its way or the highway is a reminder that, as Senator Dianne Feinstein might put it, the dogma lived just as loudly in the Protestants as in the Catholics.

Human affairs are morally complex and attempts to simplify them—even for supposedly well-intentioned purposes—are almost always bound to come up short. Combine the fraught history of anti-Catholic prejudice with the varied successes and failures of public education, and that complexity is heightened.

Although this echoes contemporary debates about school choice in some ways, that option was not a practical reality in 1844, when state-supported universal public education was the vision of a few dreamers and decades from becoming a reality.

Assimilation, lately a word associated with oppression, was then a stated purpose of public education, along with the instilling of republican virtues. The goal of the education establishment was to make good American citizens out of the rabble of ordinary Americans, including those new to our shores. But while immigrants were eager to become good Americans, to them, that did not mean abandoning their religious beliefs. Indeed, they rightly understood that America was supposed to be a land where that wasn’t necessary.

The insistence otherwise by the Protestant majority inspired the creation of a separate, private, sectarian education system—providing Catholics a choice, but essentially forcing them to pay twice, for private tuition along with the taxes that supported the public schools that refused to accommodate their religious sensitivities.

“Redress by Mob Law“

The struggle begun there—for an equitable way for every family to have a chance at the education that best suits their children’s needs—continues today. So does the struggle to deal with mob violence as a political tool.

The challenges of mid-19th century anti-Catholicism, educational choice, and urban violence are not directly relevant to the early 21st century because the contexts are so different. Today’s nativism, for example, is not anti-Catholic. There is no enslaved workforce in half the country today. The land between the Mississippi River and the West Coast is not virtually empty of White settlers nor peopled by bands of nomadic hunter/gatherers. Every major city (at least for the time being) has a professional police force. Religion has been expunged from public schools. The mainline Protestant hierarchy, to the extent it continues to exist, is not much of a force in politics.

That does not mean we have nothing to learn from the experiences of the Philadelphia Bible Riots. It simply means we should be reluctant to draw straight lines and make parallel arguments based on those experiences. Happily, Schrag spends little time doing this and most of his time telling us what happened, often at a precinct-by-precinct level worthy of Michael F. Holt.

Schrag has dug deeply into the archives, and the time spent there shows up on the page. The running street battles are rendered in amazing detail—block by block, sometimes even house by house. Key players’ biographies are full enough to provide context for their actions without bogging down the narrative. This is the first full-length treatment of the Philadelphia riots in almost half a century, and it should more than suffice for most readers for some time to come.

Academics will continue to debate the causes and cures, and whatever applications each might have for the modern world. But the useful lesson from the Philadelphia riots of 1844, the mob assassination of Joseph Smith, and countless other examples across the centuries, is that those with power will always act to defend that power and are not too particular about how they do it. It makes little difference if that power is derived from positions of authority in government, business, religion, the media, academia, or any other institution. If mobs, in the street or online, will help them achieve their ends, they’re willing to exploit them, ignoring Lincoln’s admonition that “there is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.” The question—in 1844 as it remains today—is whether the authority of the state will be employed to quell the mob or to augment it. The former is the foundation of ordered liberty. The latter is something else entirely.