The Rise of the Nones

In Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America, scholar Stephen Bullivant explores the most discussed phenomenon in American religion today: the so-called “rise of the Nones.” Nones are people without a religious affiliation; when asked on surveys to identify the religion to which they belong, they check the box that says, “no religion,” or “nothing in particular,” or “none of the above.” Starting about thirty years ago, the percentage of Nones in the United States has risen dramatically, from something like 5 percent in the University of Chicago’s well-regarded General Social Survey (GSS) in 1990 to something like 25 percent today. That’s roughly 60 million Americans.

As Bullivant, a theologian and sociologist with positions at St. Mary’s University in London and the University of Notre Dame in Sydney, explains, this percentage seems likely to increase in the near term. According to the GSS, about a third of Americans below the age of 30 are Nones, though the percentage of Nones among the youngest Americans, so-called “Generation Z,” is a bit less. Although people sometimes become more religious as they age, that seems not to be happening with today’s Nones. “Barring some Great Millennial Revival,” Bullivant writes, the proportion of the religiously unaffiliated seems likely “to grow and grow for the foreseeable future.” He sets out to explain why this mass disaffiliation is occurring and what it might mean for American society.

That the rise of the Nones represents, in Bullivant’s words, “a social, cultural, and religious watershed” is not a new observation. What makes his book original and worthwhile, in addition to the engaging writing and interesting case studies, is his focus on an important factor that scholars sometimes overlook. The vast majority of Nones, about two-thirds or three-quarters, weren’t born that way. They made a conscious choice to disaffiliate from the faith traditions in which they were raised. They converted, in other words, from having a religion to not having one: they are, in his phrase, “nonverts.” Focusing on nonverts specifically, rather than Nones generally, is a useful way to understand the changes that are roiling American culture.

Most American nonverts are former Christians. That’s simply a matter of numbers. The large majority of Americans historically have identified as Christian and continue to do so today. Most Americans who abandon religion, therefore, abandon Christianity. (Bullivant points out that, although people stereotype Nones as White, “as a group, the religiously unaffiliated are as racially diverse as the country as a whole.”) To say that America is becoming less religious means that it is becoming less Christian in social and cultural terms—that Christianity, in Bullivant’s phrase, is less and less our “default setting.” Hence the subtitle of his book. If current trends continue, he predicts, the United States will become an “ex-Christian” nation.

As Bullivant writes, many in American society find this transformation “exhilarating,” since it represents a weakening of unjust “Christian privilege.” Others find it “profoundly disorienting and distressing” and believe it will entail “an all-out assault on religious freedom, morality, and general decency.” Bullivant doesn’t take a side. Rather, he describes the factors that impel people to leave their religion and tries to predict possible long-term consequences for American life. He does so by interspersing chapters that describe big-picture trends with others that focus on the personal stories of nonverts from different faith traditions: former Mormons, Mainline Protestants, Evangelicals, and Catholics.

The chapters on individual nonverts are the most engaging in the book. Bullivant has an eye for good human-interest stories and a talent for interviewing people. Nonverts are a diverse group and generalizations are difficult. Nonetheless, patterns emerge. Nonverts from the same faith tradition tend to resemble one another and differ from nonverts from other religions.

For example, in their interviews, ex-Mormons and ex-Catholics tend to express quite negative feelings about their former religions—“passion-verging-on-hatred,” Bullivant writes. They express deep disagreement with the conservative positions of their former religions on politics and “on questions around sex, gender, marriage, family, and relationships.” They report their nonversions as disorienting but also liberating, an escape from “prohibition and guilt,” as well as hypocrisy. Former Evangelicals likewise tend to take a dim view of their religious heritage, especially its affinity with conservative politics and sexual morality. Just “follow the popular Twitter hashtag #exvangelical,” Bullivant advises, to get an idea.

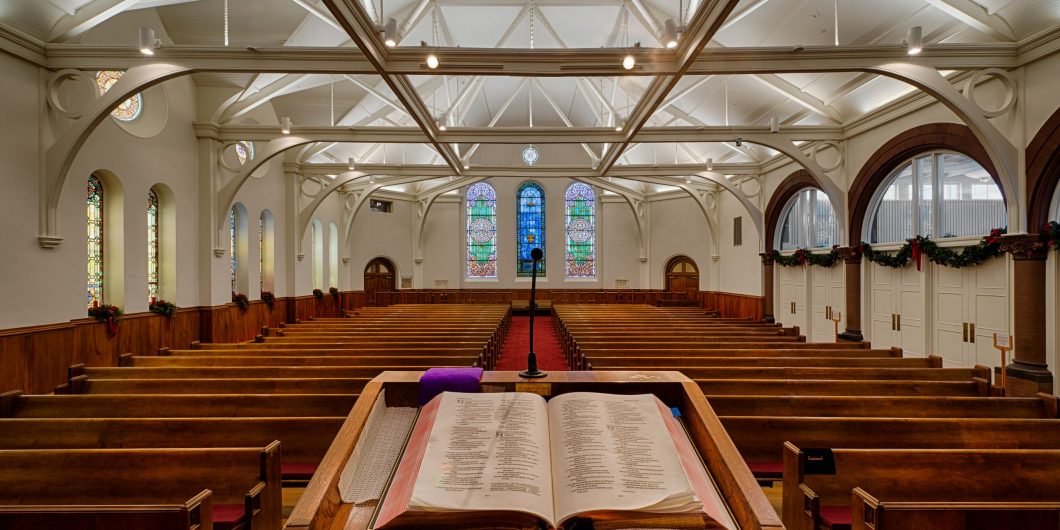

By contrast, nonverts from Mainline Protestantism tend to view their former religion with indifference. “It’s not like I hate it,” one former Presbyterian says. Nonversion from the Mainline typically does not involve “great spiritual crisis or trauma.” People simply lose interest and find other things to do on Sunday mornings. This may be the case, according to Bullivant, because many Mainline churches have themselves become quite secularized in the past fifty years, downplaying theological commitments in favor of a broader humanitarianism and social consciousness. Not much exists to hold believers in Mainline churches when they start to wander. For many Americans who have disaffiliated from the Mainline, he writes, “there seemed to be very little actual ‘religion’” in their churches in the first place.

Religion-specific factors aside, Bullivant offers several reasons for the great disaffiliation America has experienced in the past thirty years. Some are familiar and persuasive. Bullivant points to the ways in which the sexual revolution has become entrenched, even conventional, in American life, putting serious pressure on faith communities that hold to traditional sexual morality. (On the other hand, Mainline churches, which have accommodated the sexual revolution, have suffered the greatest losses.) He shows how 9/11 caused many Americans to question the benign view of religion they had, and how the internet, which offers possibilities for worldwide virtual communities of the religiously disaffected, has served as a catalyst for changes already underway.

If current trends continue, American religion will be polarized between very committed believers and people who reject organized religion entirely. That’s not a recipe for a harmonious society.

But some of his explanations are not so persuasive, including some that have received the most attention in the media. For example, he argues that the end of the Cold War had a negative effect on religious affiliation in the United States. During the Cold War, he observes, religious affiliation served as a proxy for Americanness: we were a religious people, as opposed to the godless Communists. Once the Communists were defeated, religion faded in importance as a cultural marker and Americans felt freer to leave religion behind. There’s something to this, but it seems overstated. Western Europe also opposed the Soviet Union, and religious disaffiliation was already underway there long before the Berlin Wall fell. If the fight against Communism reinforced religious commitment in America, one would have expected it to do so in other parts of the free world as well.

Bullivant rejects the conventional view that nonverts tend to come from the ranks of people whose religious affiliation was indifferent to begin with—those who were Christians in name only. Many Nones “were once genuinely believing and practicing—even ‘painfully devout,’” he writes. It isn’t simply weak Christians who are drifting away, but true believers. As a consequence, he believes, the crisis facing American Christianity is real and worse than many would like to admit.

As evidence, Bullivant points to data that shows that more and more Americans who regularly attended church as children become Nones as adults. “These were church kids,” he notes. But attending church regularly as a kid isn’t really a proxy for religious commitment; lots of kids go because their parents make them. And some data refutes Bullivant’s argument. For decades, the GSS has asked respondents to rate the strength of their religious affiliation. The percentage of respondents who say their religious affiliation is “strong” has gone down a bit since 1990, but not by much: from 37 percent to 34 percent.

By contrast, the percentage of respondents who rate their religious affiliation as only “somewhat strong” has gone down dramatically, from 14 percent to 4 percent. As in so many areas of American life, the middle seems to be dropping out in favor of the extremes on either end. If current trends continue, American religion will be polarized between very committed believers and people who reject organized religion entirely. That’s not a recipe for a harmonious society.

Of course, even if it’s only nominal Christians who are leaving, that itself reflects something important about the religion’s waning influence in American life, as Bullivant insightfully observes. Nominal adherence tells you how a brand is doing, which is why “successful sports teams often have vast numbers of casual fans.” It’s fun to root for a winning team. When a team falls on hard times, its fair-weather fans desert it. More than anything else, it seems, that describes what’s happening to American Christianity right now.

Bullivant is quick to point out that American Christianity, even conservative Christianity, is by no means dead. American Christianity still has many millions of followers and great spiritual resources. Indeed, traditional religions in general have shown some surprising resilience lately. As Bullivant points out, the culture wars have done wonders for ecumenism, encouraging conservative followers of many faith traditions—Catholics, Evangelicals, Mormons, Orthodox Jews, and so on—to make a common cause. Still, Bullivant’s basic point, that “America is demonstrably becoming less religious than it was,” seems correct. Nonverts give a good sense of exactly what is going on.