Scholars and pundits are suddenly interested in the section disqualifying insurrectionists from offices. But text and history don't offer clear answers.

The Sectional Politics of Reconstruction

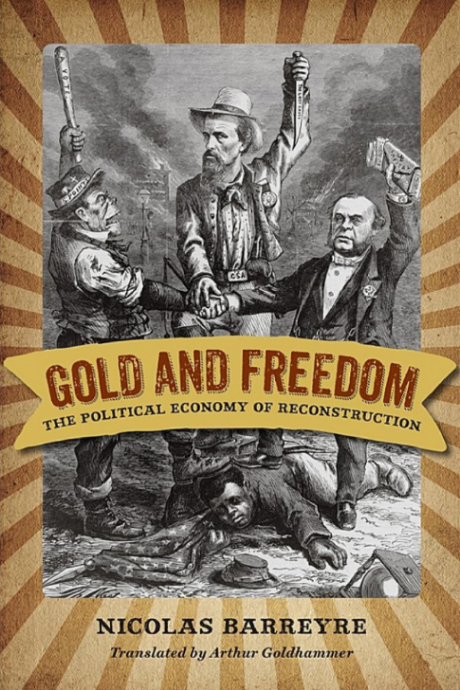

Gold and Freedom is an ambitious account of Southern Reconstruction after the Civil War interwoven with national currency and tariff policy. Nicolas Barreyre, Associate Professor at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, views Reconstruction as a reordering of the American republic that exceeded in scope the constitutional-legal problem of restoring the former Confederate states to the Union.

According to Barreyre, the Southern project called for a redefinition of the American nation, citizenship, the relationship of the people to the body politic, and “the economic model and the type of social relations on which it depended.” In short, “it is impossible to understand Reconstruction apart from the economic debates that engulfed the nation.”

Under the rubric of territorially based state sovereignty, sectionalism was a formative feature of the American republic. The concept was ambiguous, however, insofar as sections provided ground for unification of parts into a whole or separation into independent confederacies. After decades of debate, sectional conflict over slavery between the North and the South resulted in Civil War. The fundamental purpose of Reconstruction was to induce in, or otherwise impose on, the seceded states national constitutional standards of republican government.

Barreyre argues that although Democrats and Republicans expressed fairly consistent views on the reform of the former Confederates states, they were deeply divided on sectional economic issues. This political dynamic ultimately “transformed Reconstruction” and “turned the South into a Democratic fiefdom.”

Amid the debate over the principles on which republican government depended, writes Barreyre, “it is remarkable that the money question gained any traction at all, let alone became such an important political issue.” That it did so was owing in part to Section 4 of the Fourteenth Amendment, providing that “the validity of the public debt of the United States incurred . . . for suppressing insurrection and rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

The question posed in public policy concerned the convertibility of soft paper money (greenbacks) into hard money (gold). A second issue concerned the economic justice of low-revenue tariffs to pay for governmental administration, in contrast to high tariffs to protect domestic industries.

Military defeat of the Confederacy invalidated slavery-based sectionalism. The sections that legitimately qualified to engage in national policymaking were the Midwest and the Northeast. Barreyre seeks to explain how sectional economic issues contributed to Reconstruction’s aims of redefining citizenship and transforming race relations.

Midwestern agricultural and Northeastern commercial-industrial sectionalism signified “a geographic overdetermination of Americans’ economic relationship to their nation.” Although secondary to political parties, Barreyre notes that sections “structured the political field and introduced a spatial dimension.” To confine a party to one section was to suggest that it would not represent the entire country.

“In the aftermath of the Civil War,” he observes, “politics was also a matter of geography,” and “National legitimacy required a party to represent every section to some extent.”

Monetary policy, the first major issue of political economy examined in Gold and Freedom, was a staple of partisan competition. In 1862, Congress authorized the issuance of Treasury notes, said to be “as good as gold,” as legal tender for all debts public and private. Initially Democrats and Republicans supported the withdrawal of greenbacks from circulation in order to increase their value relative to gold. In 1868, however, Democrats sectionalized the money issue.

At stake in the currency debate was the structure of society and the kind of economic relations the American people wanted. Ideological polarization gave rise to “sectional confrontation.” At a time when political parties were incapable of coherent policymaking, sections were useful in framing the money question. More politically metaphorical than geographic-territorial, sections are in Barreyre’s account historical constructs that transcend “mere spatial extent.”

Tariff policy was a second economic issue that invited policy formulation along sectional lines. During the Civil War, tariffs became a protectionist instrument to redistribute wealth in the name of social justice. In contrast, free trade proponents argued for lower tariffs for government revenue purposes. Because neither political party had a consistent position, sectional considerations were relevant. Sections were social constructs that competed with parties and lent a geographical dimension to economic issues.

Barreyre summarizes: “This complex reality partly explains the political course of Reconstruction: it was through the competition between the parties and the sections that the political economy became mixed up with the social and institutional reform of the South.”

The second half of Gold and Freedom concerns Reconstruction policy. The question posed is “what kind of society Americans wanted to build in the wake of the Civil War.” A “newly important concept—national citizenship”—was the fundamental issue to be resolved. “Surreptitiously, almost illegitimately,” Barreyre asserts, “economic issues influenced the debates.”

Belligerent enemies during the Civil War, the United States of America and the Confederate States of America after the restoration of peace reverted to their identity as sectional antagonists. Succeeding slain President Lincoln as the Chief Executive, Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson offered amnesty to all but the wealthiest ex-Confederates and appointed provisional governors to organize loyal state governments and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment prohibiting slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. The Republican-controlled Congress, refusing to seat representatives from the seceded states, adopted the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Fourteenth Amendment recognizing the citizenship of all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and a series of acts imposing military governments in the seceded states. The states were required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and enfranchise black citizens.

Barreyre says Reconstruction created a “new situation” that “affected the whole dynamic of the political system” and encouraged the emergence and crystallization of economic sectionalism in the North. For example, the Bankruptcy Act of 1866 was aimed at Southern moratoria on debt recovery. Because the law was national in scope, however, it was a threat to Midwestern homesteaders and was subsequently remedied. Barreyre asserts that the statute exposed “a spatial contradiction at the heart of Reconstruction.”

Confronted with hostile Southern governments, Republicans sought to reinforce federal powers of intervention that “brought them face to face with local economic interests in the North.” Reconstruction “created a context favorable to the crystallization of the opposition between the Midwest and the Northeast.” Even when Republicans won elections decisively, the tariff and money issues “retained their destructive potential.”

In 1867, Ohio Republicans placed on the ballot a referendum on black suffrage, linked with the money question, which was rejected. Its defeat suggested that “Reconstruction was no longer enough to win elections,” and that it would be impossible to defeat the Democrats without concessions on government finances.

Some Midwestern and Northeastern conservative Republicans believed the currency question outweighed radical Reconstruction plans to reform the South. Sectional differences on economic issues threatened the future of the GOP and Reconstruction.

Following the Radical Republicans’ failure to remove President Johnson from office, General Ulysses S. Grant’s election as President in 1868 heralded peace and augured the end of Reconstruction. In the Fifteenth Amendment, Republicans prohibited denial of the right to vote on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, with the intent of giving blacks the means to defend their liberty and property. Southern states nevertheless excluded blacks from voting by the device of literacy tests previously used by New England states to deny suffrage to immigrants.

The census of 1870 provided the ground for a new sectional balance between the Northeast, the Midwest, and the South. Because Congress was constitutionally required to legislate for the whole country, it became impossible to pass bills applying only to former Confederate states. Barreyre explains: “The new institutional equilibrium—based on an altered role for the federal government and a new sectional balance—meant that the fate of Reconstruction would be tied to economic issues in unprecedented ways.”

Republican unity depended principally on supporting Reconstruction civil rights policies in the South. The party was vulnerable, however, on the matter of Southern white violence and the economics of the currency question. Congress passed civil rights enforcement acts in 1870 and 1871 authorizing the federal government to take control of local governments in order to suppress Ku Klux Klan violence against blacks. Naturalization laws were also adopted permitting the federal government to interfere with Democratic voting fraud in New York and other Northern cities. Barreyre states that “the intersection of debate on economic issues with debate on the Enforcement Acts ensured that sectional tensions would spill over onto Reconstruction.”

Offended by the practices of the Boss Tweed ring in New York City, a partisan faction calling themselves Liberal Republicans advocated civil service reform. In the presidential election of 1872, “an eclectic mix of anti-corruption reformers, independent journalists, more or less marginalized Republicans, and Democrats seeking to capitalize on the new movement” fell in with the Liberal Republicans to support the bizarre candidacy of newspaper editor Horace Greeley. President Grant easily defeated the Liberal Republican revolt, which stemmed from “the intersection of sectional tensions over economic issues and Reconstruction.” Republicans were on notice to be more cautious about federal intervention as Southern Democrats prepared for “head-on racial confrontation.”

In 1873, unrepentant Southerners deployed a “terrorist strategy” to take back political power in reconstructed state governments, while a financial panic provoked an economic crisis in the North. The sectional balance was altered in favor of the Midwest as against the Northeast. Republicans divided on sectional lines while Democrats from the Midwest and the South joined forces to reinstate the circulation of greenbacks in a bill vetoed by President Grant. The war to preserve the Union may have been won, but a mere decade later, one observer could write: “Political cohesiveness has become almost an impossibility. . . The day is fast approaching when there will be no politics in the country undisturbed by local measures and unfettered by the clamors of sections.”

To retain power, Republicans adopted a sectional compromise between the Midwest and the Northeast on economic issues while acquiescing in white supremacist rule in the South. The party’s retreat was ironically marked by the Civil Rights Act of 1875, intended as a tribute to Radical Senator Charles Sumner (R-Mass.), which proposed to regulate social relations between individuals by prohibiting discrimination on account of race in transportation and places of public accommodation. The act was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1883.

The failure of Radical Reconstruction in the South was acknowledged in the compromise of 1876, which settled the contested election between Democrat Samuel J. Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. An extra-constitutional electoral commission decided the matter for Hayes. The removal of federal forces and the restoration of Democratic Party control in the Southern states followed.

Barreyre’s sectional interpretation based on statistical analysis of congressional role-call votes augments the body of ideological, economic, and ethno-cultural interpretation of Reconstruction politics. The distinctive contribution of Gold and Freedom is its theory of sectionalism as the critical element defining the American Republic after the Civil War. Political parties that conceived themselves as national in scope were in significant part constituted by sections. Barreyre emphasizes that sections were not mere lines on the map. They were “preexisting political categories” that “could be mobilized to make sense of reality.”

Interest groups seeking political advantage sectionalized economic issues. Lacking boundaries and institutional existence, sections “constituted a strong cultural presence.” They “remained relevant to the way Americans understood the space they lived in—their territory.” The “vagueness of sectional boundaries was a plus, because it meant that the geographical definition of each section could adapt to its semantic content.” Sections received (small “r”) republican validation by participating in national politics to control constituents’ local interests.

Barreyre concludes with a kind of historical-philosophic analysis of the nature of the American republic at the end of the 19th century. The Compromise of 1876 created a new equilibrium between parties and sections. Reconstruction was as much a national political configuration as a policy to restore the seceded states to the Union on terms of equal citizenship and civil rights. Beyond the sphere of government and politics, Reconstruction acquired a new semantic construction referring to social, economic, and cultural developments. Taken altogether, the changes formed a “new national political configuration,” comprising federal and state governments and “a particular set of power relations among the more or less institutionalized interest groups that structure the political field.”

Most significant were two major political parties and geographic sectional blocs. Sectionalism played a special role in reconstructing the secessionist states, and in generating outside the South “political dynamics that might seem irrelevant” if focused “solely on the racial question.”

Barreyre asserts that “understanding Reconstruction in terms of the political configuration calls for a spatial history of politics,” which is to say “an analysis of political processes that incorporates spatial dynamics and articulates three notions: spatial categories, scales, and places.” The “historically constructed entities known as ‘sections’” formed “an effective shorthand for expressing shared positions” on critical political issues when the parties failed to do so. The “spatial history of the political” presented itself on the scale of the national government. Partisan and sectional logics intersected at that point because the same politicians who waged party battles represented sectional interests. Barreyre says sectionalism was a “national phenomenon” because only at that level could regional confrontation take place.

In the so-called spatial history of late 19th century America, the problem was that the politics of Reconstruction had a sectional dimension of its own. It was “the policy of the North to transform the South.” The Compromise of 1876 gave rise to a structure of political equilibrium that divided the national government. Until the 1890s, in only three sessions of Congress were the three branches of government controlled by one party. Divided government resulted in a “politics of inertia” that held federal activism in abeyance.

In the 20th century, Progressive “living-Constitutionalism” dedicated to constructing a centralized administrative state obviated not only Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis of frontier-sectional democracy as a guard against centralized bureaucratic government. It also undermined the Founders’ establishment of a territorial federal republic as the constitutional ground of American liberty. Americans were the territorial people of the United States. Sovereignty resided in the people of the state in which they lived as well as in the states united as a national whole. In the 21st century, the aspirations of Progressive statism reach beyond national borders to the conceit of transnational global authority.

In this historical context, the notion of “spatial politics” has unsettling overtones. Territory defined as an area of land, and space defined as an abstract or empty geometric-scientific postulate, have radically different meanings. Architects and builders may explain their designs in terms of “molding space” to achieve an aesthetic or functional result. In a political horizon, however, the idea of infinite and unlimited space is not a wholesome or propitious motive. It is out of place especially with reference to the Founding principles of American federal republicanism, which are intended to disperse and limit governmental power.

Barreyre asserts that a spatial history of American politics is relevant today. Many Southerners defend the preservation of Confederate symbols in the name of historical reality, and cultural elites professing East and West Coast “values” are pleased to look down on the manners and morals of citizens in fly-over country. When push comes to shove over liberty and property rights, however, the instinct to defend and “stand your ground” in an emphatically territorial sense asserts itself.

American federal republicanism assumed the form of a dialectical relationship between national authority and coordinate state authority grounded in territorial sovereignty. Barreyre’s account of sectionalism in terms of the “spatialization of politics” is helpful in understanding the course of Southern and national Reconstruction. It leaves open, however, the question of what sections are made of, their significance in American government and politics, and the manner in which they are constitutive of the nature of the Union.