The War Before the War

Andrew Jackson’s presidency was launched with one of the loudest and most chaotic parties Washington, D.C. had ever seen. Following his inauguration, which had been a formal and somber affair given the absence of his recently departed wife Rachel, Jackson’s supporters took the city by storm with feasting and heavy drinking. The White House was soon overcrowded with enthusiasts trying to shake the hand of the Hero of New Orleans. As the partying continued, glasses were broken, fine china was destroyed, and the furniture left in ruins. In the mayhem, there was even the fear that the enthusiastic crowds would press Jackson to death. Commenting on the day, the Washington socialite Margaret Bayard Smith observed that “the Majesty of the People had disappeared” to be replaced by “a rabble, a mob scrambling, fighting, romping.”

Centering on the issue of slavery, and the strong emotions it produced in its fiercest critics and sternest defenders, J. D. Dickey’s The Republic of Violence attempts to illustrate just how chaotic, unruly, ugly, and often violent Andrew Jackson’s America could be. Weaving together disparate figures from across the young United States, Dickey sets out to explain how antislavery activists found their voice, despite violent attempts to silence them.

Beginning in 1833, Dickey traces the birth pangs of the antislavery movement, outlining its development from a motley crew of unorganized but alarmed activists into a professional network of moral crusaders. Though William Lloyd Garrison is known to us today as an unwavering abolitionist firebrand, Dickey uses Garrison throughout his book as his symbolic stand-in for most of the antislavery movement. While he had always opposed the slave trade, Garrison had originally supported the efforts of the American Colonization Society, which sought to resettle free blacks in Liberia. But soon enough, in the face of such inhuman bondage and black protest, Garrison transformed into a radical and immediate abolitionist.

As preachers, ministers, and missionaries stormed the nation with Bibles in hand, ordinary Americans felt called to embrace moral reform.

As Dickey chronicles, Garrison was hardly alone. Many white Americans acknowledged the immorality of slavery whilst believing, naively, that the problem would eventually solve itself through legal reforms, technological improvements, and cultural change. Unsurprisingly, black Americans, both enslaved and free, were far less optimistic about the direction of the country and sought to challenge the republic to live up to its own proclaimed values of liberty. With their lives as living testimonies, black Americans sought to awaken the nation to its hypocrisy and rattle the mentality of white Americans who casually benefitted from the evils of slavery, even if they did not hold slaves themselves or even desire to do so.

At the heart of this transformation, claims Dickey, were the revivals of the Second Great Awakening. As preachers, ministers, and missionaries stormed the nation with Bibles in hand, ordinary Americans felt called to embrace moral reform and were inspired to challenge the slave system. Revivalist meetings, Bible societies, and improvement organizations all became hotbeds for abolitionism. Given that abolitionism took on a spiritual significance, religious leaders often became prominent antislavery voices as well as authority figures within the abolitionist movement. Though the importance of religious influence and reasoning is highlighted by Dickey, he never goes into much detail on the theological and exegetical logic behind their antislavery reading of Christianity. He contents himself with descriptions of each denominational tradition. Even so, Dickey does an excellent job explaining the interconnectivity of religious fervor and abolitionism.

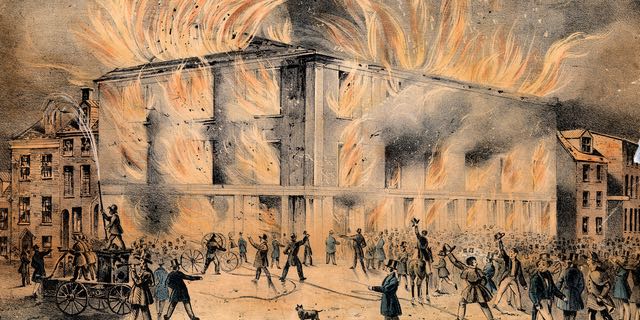

By raising the temperature on slavery through protests, petitions, and in print, abolitionists put themselves in the crosshairs of a public who was often unfriendly to them. Even those sympathetic to the cause often decried these early activists as ‘radicals,’ depicting them as starry-eyed dreamers with no sense of political reality, or as annoying self-righteous moralists who had taken their beliefs to an unhealthy extreme. The texts selected in many historical studies of the rise of American antislavery might give one the false impression that disputes between abolitionists, moderate reformers, and pro-slavery activists were merely an intellectual exercise. The Republic of Violence shows how easily such disputes could devolve into mob violence, challenges to duels, vandalism, and murder. With page after page of horrific displays of brutality against antislavery activists, The Republic of Violence certainly lives up to its title.

Yet, as Dickey carefully explains, the specter of violence was not a one-way street. Like many dissenters living in a system hostile to their views, abolitionists continually debated whether violence should be a tool employed in the quest to end slavery. Some, like David Walker in his Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829), argued that slaves should resist their captives just as the Israelites in Egypt had done. But others, like the pacifistic Quakers, believed that such actions would condemn their souls and make them no better than those who had used bloody means to enslave black people in the first place. Garrison also remained committed to nonviolence, much to the annoyance of many of his supporters. Because of these tensions, slave revolts, like those led by Stono, Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and most famously the Haitian Revolution, were sources of both inspiration and concern for antislavery activists, and an ongoing point of debate within the movement. Thanks to his careful and sympathetic analysis, Dickey makes the stakes of this dilemma clear, and the debate over ‘means and ends’ incredibly real.

Garrison comes off as particularly egotistical, unwilling to heed any sort of criticism and eager to shut down rivals to his leadership.

Even as he presents the messy fault lines of the young Abolitionist movement, Dickey does not shy away from their unflattering qualities. Readers will still be inspired by their courageous example, but Dickey shows the abolitionists’ human failings, revealing how they could easily fall prey to petty infighting, leadership battles, unrealistic expectations of their followers, and plenty of money problems. For example, while on a tour of the United States, the British abolitionist George Thompson frequently insulted audience members who disagreed with him. He publicly denounced fellow abolitionist Francis Augustus Cox as a coward at the New York meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Dickey also highlights the less desirable qualities of abolitionism’s leading propionates, such as their fierce nativism and anti-Catholicism, as well as their racist views on black intelligence and race mixing. Garrison comes off as particularly egotistical, unwilling to heed any sort of criticism and eager to shut down rivals to his leadership. Readers might be taken aback by some of his language towards the Irish, who he regarded as “foreigners of the lowest grade.” Such dynamics inject drama into an already vivid history, showing that abolitionists were as human as they were heroic.

One particularly striking theme in Dickey’s work is the price of peace. While The Republic of Violence is full of slavery’s vocal southern advocates, eager to crush the infant antislavery movement, Dickey also shines a light on the various attempts to avoid the subject of slavery at all costs. For example, given the inflammatory nature of the subject, Postmaster General Amos Kendall instructed Southern postmasters to withhold delivering abolitionist material, a move endorsed by President Andrew Jackson. Despite being one of Tennessee’s largest slaveholders, Jackson said very little in the defense of slavery publicly, undoubtably aware how explosive the subject could be. But he also believed the worst conspiracy theories concerning abolitionists, supposing they were hellbent on dismantling the Union. Ironically, the effort to repress antislavery literature only served to further galvanize abolitionists and inspire alternative means of distribution. This in turn provoked efforts to hunt down and mob southern allies to the cause of abolition.

Given this tense environment, Dickey notes the difficult political terrain Democratic and Whig politicians had to traverse and the lengths they would go to try and maintain the peace. Controversy was also bad for business, and many northern businesses hid their associations with the slave south, for fear of provoking a boycott. But as a slaveholding republic, peace, was regularly on the terms of the slaveholders, with abolitionists continually disparaged as willful provocateurs at best, and at worst, terrorist-like saboteurs to the social order. Though it would be a mistake to say that the Civil War was inevitable, peace seems almost unthinkable because of abolitionists and slaveholders’ constant efforts to disrupt the uneasy harmony between the free and slaveholding states, and break up the shaky alliances of the political parties. After all, peace with slaveholders would have been nothing short of a deal with the devil, or as Garrison put it, a “covenant with death” and “an agreement with Hell.”

The Republic of Violence is a page-turning history of a particularly turbulent period within the American experiment. It stands as a stark reminder of the power and perils of free but unpopular speech. Readers will no doubt find many of Dickey’s tales of political intimidation, protests turned into riots, violence in the streets, and activistic infighting, all too familiar. While our current political moment is nowhere near as hostile and as polarized as Jacksonian America, Dickey’s engaging tale demonstrates that many of the questions, issues, and dramas faced by the fledging abolitionists have echoes in our own time.