The Witches of Springfield

It’s a few years since I’ve been to Springfield, Mass. And I have to say that it never gave me the impression of being a place for the supernatural. It’s one of those rare towns that is an Amtrak crossroads. You can head west on the Lake Shore Limited and go all the way to Chicago, or take the Vermonter South to New York, or head up to St Albans or East to Boston. Three hundred and eighty years ago, it wasn’t the crossroads of anything: it was close to the edge of the whole world its residents knew.

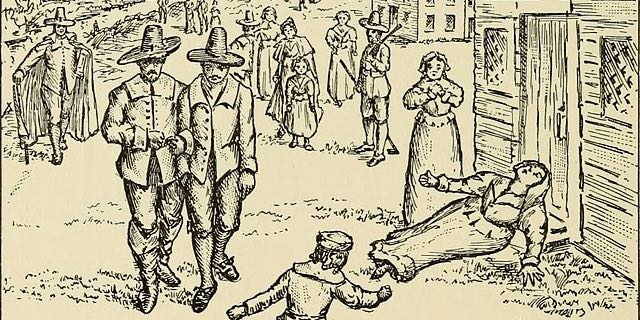

Back then, Springfield was a place where the contradictions of magical belief and frontier society came to the fore. According to Malcom Gaskell, “what happened at Springfield was both America’s first witch panic and an overture for Salem, America’s last.”

It was 1645, when brick-maker Hugh Parsons and his wife Mary were charged with witchcraft. Settlers in New England had been rocked by news of the Civil War back in the old country. And cracks were emerging in the theological system that had been established by the Puritan authorities. Unlike some towns in New England, where entire parishes had upped sticks and emigrated, Springfield’s population was a diverse collection of people from different parts of Britain. They came with their own belief systems and habits, and presumably prejudices, carried along with them. The town father, William Pynchon, had to attempt to steer this ship of souls with the assistance of the local minister.

Life was hard, and many struggled. As back in Britain, infants born in this new world died with depressing regularity. Families faced the vicissitudes of crop survival, and clung to a grim livelihood, believing at least in a Calvinistic predestination. Hugh had a marketable trade, but still found it hard to stay out of debt. He also seems to have been something of a strange fellow. He was constantly dropping in on his neighbors uninvited, for no other reason than to sit at their table and have a smoke. Was he bored? Nosy? Oblivious to social cues? Who knows?

But this kind of ambiguous behavior could add up in a case about someone being a witch. As for Mary, she was apparently witch-obsessed. She talked of witches, and accused others before settling the blame on her husband. She was a gossip, he was unreliable in business, and their bad marriage apparently annoyed the town.

Was this enough to make the Parsons witches? Some of the accusations were odd and trivial, like misplaced tools suddenly reappearing. Another man thought Hugh had cursed him to fall from his horse. Some witnesses saw ghostly apparitions, but the most serious charge against Hugh was that he had bewitched his own child to death. Did all the townsfolk truly believe this? As Gaskill points out:

Though wicked, witchcraft was a slippery crime, suspended between fantasy and reality, credulity and skepticism. Most people believed in witches; the thornier question was whether an individual could reasonably be hanged on the testimony of her neighbors.

William Pynchon, far from being a keen witchfinder, was skeptical. (He had other doubts about Puritan doctrine, and published a book that the Massachusetts authorities deemed heretical.) Nonetheless, this was a world of harsh punishments; even adulterers were hanged in New England. And a court in Boston would decide the Parsons’ fates.

Dying women and children, failing crops, half the townsfolk were moving in a swirl of grief and financial struggle.

Mary’s fate was foreclosed by her confession to murdering one of their children – through human, not magical means. As Gaskill suggests, this confession may have been false, but it is hard to know. She died in prison before she could be hanged. A modern reader might ascribe Mary’s behavior to post-natal depression, and wonder whether Hugh was also having some kind of a breakdown. At one point Gaskill explains that wife-beating was illegal, as though that in itself answers any readers’ lingering questions about the Parsons’ marriage. (Domestic violence has always been underreported, whatever its legal status.)

But such truths remain just out of reach, unmentioned in the record. Gaskill’s years of research mean he takes us through the months leading up to the witch trial, and narrates Mary’s life before she made the decision to emigrate. She was Welsh and poor, and had joined a fervent Protestant congregation after being abandoned by her first husband. Her church connections arranged her passage, in order to work as a nursemaid in the new world. Hugh’s background is cloudier, making him the more mysterious figure.

Kai Erikson, in his 1966 sociological study in deviance, focusing on Massachusetts Puritans, wrote:

One of the surest ways to confirm an identity, for communities as well as for individuals, is to find some way of measuring what one is not.

To a Puritan settler, the measure was to be English, saintly, and saved, rather than Indian, foreigner, witch. On a frontier, these boundaries hardened, with fear of the Other close by. Gaskill suggests that this state of constant anxiety would have contributed:

To stray from the homelots, as children often did, was to sense the eeriness of isolation, feelings of foreboding and of being watched.

Add in the quotidian irritations of living in a small town, and it’s easy to imagine resentments curdling into accusations. It wasn’t a great stretch to believe in the actual witchcraft or demonic possession of one’s neighbors in a worldview that already encompassed ill fortunes, evil spirits, and the wrath of God. As Gaskill reminds us, witches weren’t figures of fantasy: they were felons.

Witchcraft was not some wild superstition but a serious expression of disorder embedded in politics, religion and law. Witches were believed to invert every cherished ideal, from obeying one’s superiors to familial love. They were traitors and murderers, bad subjects and neighbors, delighting in spite and mayhem.

But the fervor of suspicion arose due to local conditions. Historian Mary Beth Norton has tied the Salem witch panic to town leaders already in a defensive crouch after fleeing Indian raids on the frontier. They were determined to assert dominance over threats appearing from magic or human sources. In Springfield, it was a time of political turmoil too—as well as individuals pushed to the limit. Dying women and children, failing crops, half the townsfolk were moving in a swirl of grief and financial struggle. The desire to place blame somewhere is universal, and theirs was a cultural context where witchcraft was available.

The religious frenzy of the Reformation and English Civil War only increased mistrust, and (like “heretic”) the label “witch” was political as well as spiritual. The conflicts of the Thirty Years War and English Civil War were about political power as much as religious doctrines, and across Europe witch trials were fiercest in regions of religious schism. This rippled across to the New World, where Puritan settlements were defined by religious adherence.

The tragic story of Hugh and Mary Parsons is not unknown to historians, but was a minor footnote in the history of early Massachusetts. Gaskill’s careful tracing of their lives through the paperwork of the trial and the early records of Springfield bring their world into clearer view. Feeling sympathy across 300 years is easy, even as I was left wishing some more of the gaps in the story could be filled.

Unlike Salem, Springfield today makes little of its witchcraft connection. There are no pointed hats or broomsticks on street signs. Did the rest of the town regret Mary’s case? Or were they simply glad the finger hadn’t been pointed at them?