Turning Right

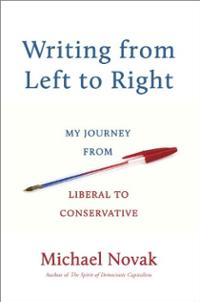

Michael Novak’s evocative new memoir, Writing from Left to Right: My Journey from Liberal to Conservative, is a quick and enjoyable read that will engage many readers in familiar terms. Its story is one of awakening, of an expansion of mind from the narrow constraints of what he seems to regard as a facile liberalism to the embrace of a nuanced and variegated conservatism. It is, as one would expect, clearly and compellingly written—at times coolly persuasive, at others warmly moving. Its only disappointment is also a tribute to Novak: Dr. Johnson said of Paradise Lost that none ever wished it longer. Precisely because Novak is such a complex thinker, one does wish this book were a bit deeper.

At times its treatment of Novak’s former philosophy seems shallow, depriving the reader of the deeper conversation he urges in the book’s conclusion for contemporary politics. Instead, he at times oddly condescends to his younger self, treating the philosophy he outgrew almost as a child’s plaything rather than a serious system of thought with which he came seriously to disagree. Politics emerges in sharply divergent categories that one could describe as Manichean except that Novak, in his defense, does not moralize them—Left vs. Right, socialism vs. capitalism, statism vs. civil society—that leave little room for the subtleties on which the common ground he seeks can be forged. Still, conservatives will find a compelling case for conservative ideas in these pages. He presents the arguments for such policies as lower capital gains rates in full yet simple—one is tempted to say “Reaganesque”—terms.

Novak moves between past and present to interject commentary as he goes. It is, if occasionally unsubtle, always insightful. His dissection of the new multiculturalism—compared to the “new ethnicity” he identified in his landmark The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics—is illustrative: Novak explains the rootedness of ethnicity in mediating institutions like family and the particularity of cultures, as opposed to the unattainable and ethereal universality of multiculturalism. “Each of us is limited, singular, concrete. We are, none of us, Universal Man or Woman. On the other hand, by virtue of our unlimited drive to inquire, to seek understanding, and to expand our capacity for sympathy, we are each potentially open to the universality of our species.” (131-132)

Novak at times exhibits troubling symptoms of Presidential determinism: executives crow; suns rise. There was thus a “Reagan boom of new tech companies” in the 1980s (181), President Clinton (by imitating Reagan) “kept the economy strong and vital” (xvii) and the Arab Spring, having followed Bush II’s Iraq war, seems to have happened because of it (271). This belief in the power of executives is perhaps understandable given the depth of Novak’s relationships with so many of them, but it is also evidence of the lack of theoretical subtlety that sometimes characterizes these reflections compared with his other works. Indeed, his entire journey from left to right seems to occur in simplistic bursts that one cannot help but suspect were more complex than he portrays, if only because the ideas he came to reject were more complicated than Novak acknowledges. He writes, for example, of his nagging doubts in the early 1970s, after he supported George McGovern for President:

In short, my first thought was: Socialism is a pretty good idea; it’s just that we haven’t found a way to make it work yet. Then I couldn’t help thinking: But after scores of attempts around the world to make it work, all of which failed, maybe there’s something wrong with the basic idea. . . . Socialism, I was beginning to infer, is not creative, not wealth producing. (149-150)

This is true enough, but something rings hollow, or at least shallow, about this account. Novak never seems to have been a socialist in any meaningful sense, nor was McGovern—this portrayal flirts with the unhelpful contemporary tendency to apply that label to any economic doctrine left of center—but to the extent Novak was coaxed from his New Dealer beliefs, it would be helpful to see both those beliefs and his conversion in more complex hues than the blacks and whites he presents.

Instead, Novak often presents his old ideas in what feel like facile terms, then describes a change of mind with a transitional phrase like “I saw that,” followed by a new idea, often described at a greater level of sophistication. The reader is left wanting to now how and why he “saw that.” He breezily writes, for example, on page 199:

To sum up what I learned just before and during the Reagan administration: First, economics is often counterintuitive. It would seem that the common good would be improved by a government supervising the economy from the top down, just as common ownership of property would produce a higher common good than private property.

Again, fair enough. But to whom, outside Moscow, Managua and, perhaps, Berkeley, did such a thing “seem”? It is difficult to believe a thinker of Novak’s sophistication actually operated in these simple dichotomies, nor did the Democrats he admired even as he grew distant from their politics.

Of course, a change of mind is a difficult thing to describe; sometimes it simply happens, or one does just read Hayek (153) and realize that economic order is spontaneous. Moreover, Novak is entitled to characterize his own thinking, and if it was actually this simplistic in his liberal days, so be it. But by not crediting the complexity of the ideas he shared with his ideological confreres, he is sweeping them by implication into the same one-dimensional heap. He professes admiration for them—from McGovern (“thoroughly decent” 127) to Senator Scoop Jackson (who, while a Cold War hardliner, was also an ardent New Dealer)—but one wonders whether he can have it both ways, seemingly stigmatizing himself while still lionizing them.[1]

To be sure, Novak’s conservatism is exceedingly complex, even if by the end of the narrative his ideas so closely hew to Republican Party orthodoxy—from endorsing George W. Bush’s Second Inaugural to counseling skepticism on climate change—that one wonders why he apparently affiliated as a Democrat until 2010. Novak rejects the individualism that characterizes a substantial strain of contemporary conservatism, emphasizing—as he did in The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism—that individuals are situated in social contexts and the vital importance of mediating institutions. He says he does not deny a role for government, although it is unclear what precisely that might be. He recounts a heroic struggle to bring conservatives and liberals together on poverty policy through an initiative at the American Enterprise Institute.

The skill and moral clarity of his diplomacy are also evident in these pages. As Reagan’s envoy to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, he orchestrated the first censure of a regime in the Soviet orbit (communist Poland) for human rights abuses. (216) While Novak graciously shares credit for the technical achievement with the vote-tallying tacticians in his delegation, one receives the clear impression that the modest yet unwavering moral message of a theologian made an impact in ways the diplomacy-speak of a foreign-service officer might not have. His steadfast refusal to accept a watered-down agreement on the Helsinki Round in Bern in 1986, which assessed compliance with agreements on human contacts such as marriages between citizens of different countries (Chapter 19), further testifies to the moral perspective he blended with diplomatic skill.

By far the most moving account in the memoir is his recollection of his relationship with Pope John Paul II. We are able to see their friendship in human terms, but also the Pope in the moments of both stalwart resolve and personal prayer—Novak joined him on several occasions in his private chapel—that made him such a giant of his time. Novak also honestly portrays his “great struggle of conscience” (313) when he disagreed with John Paul II over the war in Iraq in 2003.

Novak’s scattershot policy overview in his penultimate chapter is less satisfying: an attempt to cover too much ground in too few pages. It ranges from a far too simplistic account of the Bush II Administration’s policies in Afghanistan in Iraq, which appear here as nearly unvarnished successes, to a few pages on his friend Steve Forbes, to a puzzling claim that Clinton raised income taxes “only modestly” (273) when his own chart shows the maximum rate increasing by more than 40 percent. This last claim is in the service of arguing that President Reagan’s policies deserve credit for the balanced budgets of the 1990s—an argument that can be made, but that Novak needs to make in more detail, especially since he skips over the credit seemingly due to Bush I and the fact that the deficits that were erased in the 1990s had ballooned in the 1980s.

Novak is a devotee of Reinhold Niebuhr. His plea for civility, which is blended with these policy observations, commends the Protestant theologian by way of paraphrase: “In my own views, there is always some error; and in the views of those I disagree with, there is always some truth.” But by the time he has reached right on his long journey from left, Novak does not seem to acknowledge either error in the former or truth in the latter. There is little left in his worldview of either a Niebuhrian mean or Niebuhrian irony. He seems, instead, to have reached a tranquil set of clear conclusions. Having witnessed eight decades of history, made much of it and shaped through his writings a great deal more, Novak is entitled to that.

[1] Some errors of fact also give the manuscript an occasionally shallow or overly breezy feel. George Mitchell, who did not join the Senate until 1980, appears as a villain in the battles against capital gains cuts in the late 1970s (180); Jimmy Carter, who never actually used the term, is quoted diagnosing the nation with “malaise” (181); Ronald Reagan’s famed debate with Bobby Kennedy, which actually took place just after he was elected Governor of California, is located here after he left office (185); Novak attributes to Pat Moynihan, and slightly misquotes, a quotation that Moynihan actually attributed to the sociologist James Coleman (254). On the whole, however, it must be said these errors flit about the edges of Novak’s arguments rather than reaching their cores.