Why McCulloch Is Blamed or Praised But Rarely Understood

In any compilation of the greatest judicial opinions by the Great Chief Justice, John Marshall, McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) is bound to be mentioned, however short the list. Some scholars regard it as even more significant than Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which Marshall expounded on the power we now call judicial review. One thing the opinions have in common, unfortunately, is that both are widely misunderstood today. Marbury is commonly taught as though it stood for the puffed-up pretensions of judicial supremacy that attained the status of gospel truth among judges, lawyers, and law professors in the last century. And McCulloch is blamed or praised, depending on the political preferences of commentators, for allegedly writing a permission slip for Congress to do nearly anything it pleases under the rubric of “implied powers” authorized by the “necessary and proper” clause. But was that either the purpose or the effect of the Marshall Court’s decision in the case?

Marshall’s compact and elegant opinion for a unanimous Court upheld the bank’s charter as a legitimate exercise of congressional power, and invalidated Maryland’s tax as contrary to the Constitution’s principle of the supremacy of federal laws over state enactments.

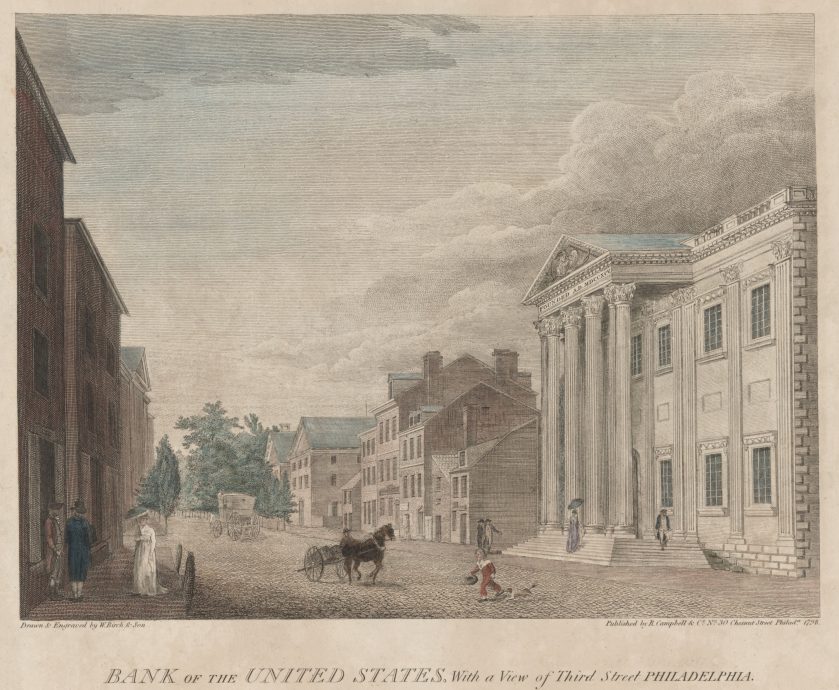

McCulloch brought before the Supreme Court a question that had been repeatedly debated in the political branches since 1791: Could Congress charter a national bank, a corporation in which private parties as well as the federal government held stock, issuing banknotes as a circulating medium of exchange, facilitating tax payments, and serving as a ready source of credit to the government? The First Bank of the United States had been the brainchild of Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, and over the opposition of figures such as James Madison in the House of Representatives and Thomas Jefferson and Edmund Randolph in the cabinet, the bank’s charter was passed by Congress and signed by President Washington. The expiration of the charter after twenty years, on the eve of the War of 1812, proved the utility of the institution even to Madison, who signed the charter of the Second Bank in 1816.

The case arose because Maryland attempted to tax the bank’s operations—by a state law of 1818 taxing only those banks doing business in the state that were not chartered by itself, which at the time meant only the Bank of the United States was subject to the tax. When the cashier of the Maryland branch of the bank, James McCulloch, refused to pay, and the Maryland courts upheld the tax, Marshall’s Court found itself confronted not only with the question whether Maryland’s tax was constitutional, but with the prior question, earnestly pressed by Maryland’s counsel, whether Congress had authority to create the bank in the first place. This of course revealed the real motive of Maryland’s legislature (and of “state’s rights” politicos elsewhere): to destroy the Bank of the United States altogether. They would be satisfied either with a ruling that Congress had exceeded its constitutional power, or a decision that permitted states to tax the bank to death.

Marshall’s compact and elegant opinion for a unanimous Court upheld the bank’s charter as a legitimate exercise of congressional power, and invalidated Maryland’s tax as contrary to the Constitution’s principle of the supremacy of federal laws over state enactments. Immediately the advocates of “state’s rights” denounced the decision, especially in Marshall’s home state of Virginia. This prompted an apparently unprecedented (and unrepeated) step for a sitting justice of the Supreme Court, when Marshall answered the ruling’s critics in his own newspaper essays in the spring and summer of 1819—writing under a pseudonym as his opponents had done, and as was still customary at the time.

The furor over McCulloch passed, though the bank remained controversial. When a bill was passed to renew the Second Bank’s charter in 1832, four years before its expiration, Andrew Jackson vetoed it, standing on his right to contradict the McCulloch decision on the constitutional question. He subsequently directed his treasury secretary, Roger Taney, to withdraw the federal government’s deposits from the bank, shaking public confidence in it for what briefly remained of its life. The United States would not have a central banking system answering to the federal government’s authority from 1836 until 1914, when the modern Federal Reserve system was created.

For two centuries, then, McCulloch has been a lightning rod of controversy. It was fitting therefore that the American Enterprise Institute should sponsor a conference on the bicentennial of the case, resulting in the present volume edited by Gary J. Schmitt and Rebecca Burgess.

Following Schmitt’s useful introduction, the volume begins with an essay by Nelson Lund, expanding on one that appeared here at Law & Liberty’s forum discussion in March 2019. As a contributor to the forum here prompted by Lund’s essay, I will not repeat all that I then said about it (and readers can see Lund’s rejoinder to me and other commentators at the link above as well). But I believe it is important to recognize the strong affinity between Lund’s view of Marshall’s McCulloch opinion and the view taken of it by Spencer Roane and other contemporaneous critics of the chief justice. Not that Lund shares the view of Roane et al. at its deepest level, with its insistence that the Constitution did not essentially change the character of the Union previously created by the Articles of Confederation. Yet like those long-ago members of the Richmond Junto, he complains about Marshall’s “expatiating without any clear necessity on the political theory of the union,” without noticing that the chief justice was rebutting arguments on that score made before the Court at length by counsel in the case.

Lund also insists that Marshall should have undertaken a more fine-grained analysis of just what made the incorporation of the bank “necessary and proper” to the execution of specific enumerated powers granted to Congress by the Constitution. Hamilton had gone into such detail in 1791; why could not Marshall have done so in 1819? But the chief justice gave his reason in the McCulloch opinion, and defended it in his subsequent essays: “the degree of [the bank’s] necessity . . . is to be discussed in another place,” namely in the legislative process.

Curiously, Lund closes his chapter by changing the subject, offering a litany of cases in which “the justices signaled that the commerce clause gives Congress authority to regulate virtually everything in human life that is not protected by . . . judicially favored individual rights.” This discussion would not be out of place in an essay on Marshall’s great 1824 commerce clause decision, Gibbons v. Ogden, but what it has to do with McCulloch is unexplained. Most of the cases Lund mentions do not cite McCulloch at all, and the Court’s reliance on it is significant only in one or two. Whatever McCulloch accomplished, for good or ill, its effect on the interpretation of the Constitution’s enumerated powers as such is pretty much nil.

In the end, like Marshall’s critics in 1819, Lund seems more disturbed by the reasoning in McCulloch than by the result it endorses, the constitutionality of the bank. But as Marshall said in one of his essays

I hazard nothing when I assert that the reasoning is less doubtful than the conclusion. . . . [T]he principles laid down by the court for the construction of the constitution may all be sound, and yet the act for incorporating the Bank be unconstitutional. But if the act be constitutional, the principles laid down by the court must be sound.

This statement makes sense in light of Marshall’s consistent adherence to a bright line between the questions that concern legislatures (and the political branches more generally) and those that concern the judiciary. As Christopher Wolfe and Adam White both recognize in their excellent chapters in this volume, Marshall’s jurisprudence differed from that of modern judges, who “have no hesitation about deciding questions of degree” rather than hewing to those of principle (Wolfe); by contrast, Marshall exemplified the “self-restraint” appropriate to a “republican rule of law” (White).

Michael Zuckert’s chapter makes an interesting case that Madison’s reading of the “necessary and proper” clause navigated a third and better way between that of Jefferson (and the Richmond Junto in later years) on the one side, and that of Hamilton and Marshall on the other. Jefferson insisted on an “absolutely necessary” or sine qua non reading of the clause, such that any power that could not be characterized as indispensably, solely the means of executing an enumerated power was to be held unconstitutional. Hamilton and Marshall, in Zuckert’s account, read the clause as authorizing any law that plausibly advanced the “objects” of the Union, broadly understood. Madison’s via media, then, was that any implied power must be shown to aid in executing the enumerated powers of the government, not the overall “objects” of the government.

I think that Zuckert, an accomplished Madison scholar, has correctly read Madison’s argument, but has been betrayed by focusing too much on some admittedly equivocal language employed by both Hamilton and Marshall. Wolfe is right, I believe, when he says in reply to Zuckert that Marshall was not “talking about the general objects of the Constitution (apart from the enumerated powers), but rather the objects implicit in the enumerated powers” (emphasis in original) as the ends to which implied powers were the means. Madison and Marshall, it turns out, are not so far apart in their reasoning after all.

The longest essay in this book, and the most challenging, is Robert Webking’s analysis of Marshall’s nine “Friend of the Constitution” essays, his second series of replies to his critics in 1819, this time answering Spencer Roane’s “Hampden” essays. For Webking, these essays shed important light on certain unelaborated elements of the McCulloch opinion itself. The most startling conclusion he draws is that “the decision was not about implied powers and did not depend on the necessary and proper clause to reach its conclusion on the bank.” Webking’s case for this counterintuitive reading rests on a reply Marshall makes in his essays to an argument of Roane’s about the difference between those powers that are additional to the enumerated powers but legitimately implied as “incidental” to them, and the mere “means” of executing enumerated powers that spring directly from those powers themselves.

Take, for example, a law providing comprehensively for the collection of revenue into the treasury. Every detailed provision for specifying taxpayers’ obligations, when they are due, how and where the revenue is to be collected and transmitted to the capital, is a means to the end of the taxing power. But these are not the employment of “implied powers”; they are direct exercises of the taxing power itself. By contrast, says Marshall the essayist, passing a law to “punish those who resist the collection of the revenue” would be an exercise of an “incidental” or implied power, one that is “necessary and proper for carrying into execution” the taxing power, but not so directly an exercise of the taxing power as to be a “means” in the narrowest sense.

Adam White describes McCulloch—as a case in which a statesmanlike Marshall exercised restraint, declining to endorse a broad agenda of nationalism in American politics—I am quite happy to say amen. Twentieth-century “big government” will have to look elsewhere than Marshall’s great decision to find its constitutional justification.

This is an important distinction, and I’m grateful to Webking for his rediscovering it. But his lengthy revisionist case for a hard distinction between “means” and “incidental powers,” with his insistence that wherever Marshall says “means” we must understand him not to be referring to incidental or implied powers, brings him to the insupportable conclusion that McCulloch is not a case about implied powers at all. Webking is quite mistaken to aver that Marshall treats the bank’s incorporation as a “means” in the narrow sense of being a direct exercise of one (or more) of the enumerated powers, and equally mistaken to deny that Marshall rests the decision (in part) on the “necessary and proper” clause. The chief justice explicitly relies on that clause in McCulloch itself, and equally explicitly he refers there to Congress’s power of incorporation as one that can be “implied as incidental to other powers or used as a means for executing them.” Notice Marshall’s use in that line of all three expressions: means, implied, and incidental. It is true that “means” is the word most often used in the McCulloch opinion. But it does not follow that Marshall understood the word always to import the narrow sense he recognized it may sometimes have in his “Friend of the Constitution” essays. Language is often equivocal, and a law may be a direct or primary means to the end of an enumerated power, as in a law specifying the mechanics of revenue collection, or it may be an indirect or secondary means to effectuating the end of such a power, as in a law punishing tax dodging with fines and imprisonment. To insist on a radical contradistinction between “means” and “implied powers” does not do justice to Marshall’s subtlety.

Abram Shulsky’s chapter, “How an Economist Might View McCulloch v. Maryland,” offers a useful perspective on the case, considering its implications for Congress’s power to create a national financial system, encourage commerce, regulate the money supply, and facilitate the payment of taxes and other debts to the United States. But the chapter makes some odd missteps. At one point, Shulsky muses about Marshall’s omission of the power “to coin money [and] regulate the value thereof” from his list of enumerated powers served by the bank, and later he concludes that perhaps “at the time, this power was generally believed to be confined to the actual minting of gold and silver into coins and had nothing to do with a ‘currency’ of the sort the bank would create—or, for that matter, of the sort we have now.”

But this was not only true “at the time”; it is true now. Neither the greenback dollars in our wallets nor the deposits electronically tallied in our banking system are money “coined” under Congress’s enumerated power on that subject. But they are no less “money” for all that. The banknotes of the old Bank of the United States were only as good as the public’s acceptance of them, and the assurance of specie reserves in the bank was the backstop of that acceptance. But no one was obliged to accept them at face value in wholly private transactions, so Shulsky is mistaken to say that “arguably Congress had delegated to a group of private citizens the authority to exercise this vital power [of creating a “national currency”] of the national government.” The Treasury banknotes of the late nineteenth century were legal tender for all debts, as are the Federal Reserve notes we carry today, but this obligatory character of its notes’ universal acceptance was never accorded to Hamilton’s bank.

As I have indicated above, the contributions of Christopher Wolfe and Adam White are the high points of this collection. Wolfe, long one of our best Marshall scholars, has the rare capacity to see Marshall’s jurisprudence as the chief justice himself saw it—as animated by a devotion to principle and an aversion to judicial aggrandizement. White’s contribution is a thoughtful consideration of what Marshall can teach us about the meaning of “judicial statesmanship.” Since in part he takes issue with an article of mine from three decades ago, I will take this opportunity to say that he seems quite ready to condemn judicial statesmanship as I described it, and I am quite ready to embrace judicial statesmanship as he describes it. And as he describes McCulloch—as a case in which a statesmanlike Marshall exercised restraint, declining to endorse a broad agenda of nationalism in American politics—I am quite happy to say amen. Twentieth-century “big government” will have to look elsewhere than Marshall’s great decision to find its constitutional justification.