Charles Fried's "Conservatism" Is a Form of Living Constitutionalism

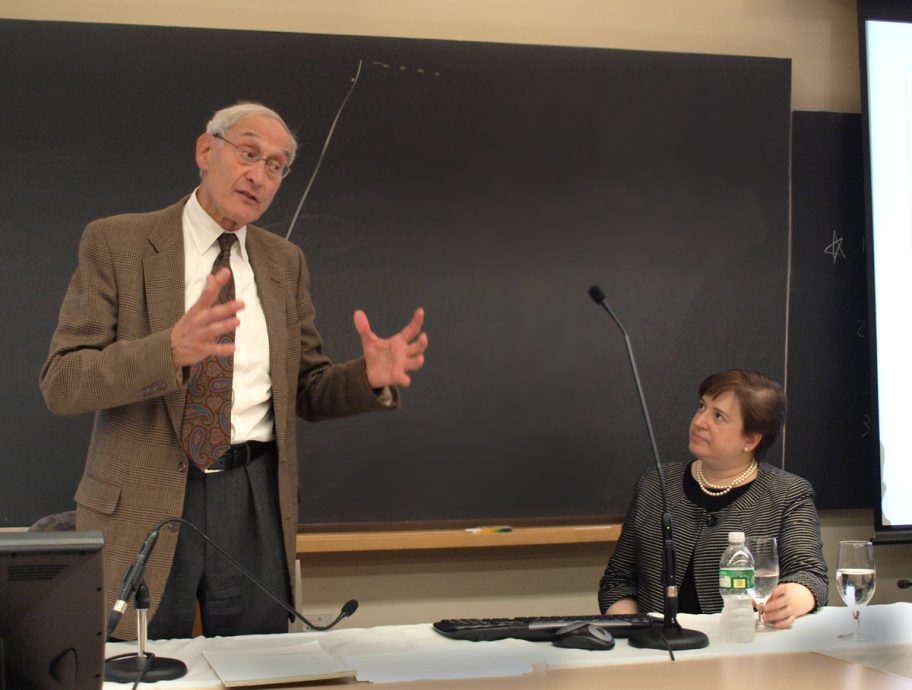

Charles Fried, a Harvard Law Professor and former Solicitor General under Ronald Reagan, has attacked the Roberts Court for failing to respect legal settlements reflected in either judicial precedent or bipartisan legislation. Fried argues that disturbing such “compromises” is not “conservative.” Fried’s arguments represent a misunderstanding of conservatism in law and ultimately are indistinguishable from living constitutionalism that is the essence of legal progressivism.

Fried does not try to demonstrate that the Roberts Court decisions to which he objects are based on misreadings of the law, but claims only that they rest on “abstractions” and upset settlements that are “working.” But Fried never even shows why these decisions are improperly abstract. Take Citizens United to which Fried now objects — even though he supported it at the time it was decided. As was noted at oral argument in the case, the logic of the government’s position was that Congress could ban people banding together in the corporate form from publishing a book about a candidate before an election. This seems a very concrete violation of our First Amendment rights. Moreover, the Citizens United Court shows that First Amendment law has long proceeded on the basis that corporations are protected under the First Amendment, including in landmark decisions, like New York Times v. Sullivan. How does Citizens United rely on mistaken abstraction rather than the neutral principles that should be the hallmark of First Amendment law?

In McCutcheon v. FEC, another case about which Fried complains, the Court invalidated a law that prohibited a citizen from giving $2,500 to multiple candidates. The government’s principal argument was that the aggregate ceiling on donations to all candidates prevented circumvention of limits to giving more than $2,500 to individual candidates, but the Court observed that there were many ways that Congress could make circumvention illegal without trenching on the First Amendment interests of giving to different candidates. This kind of less restrictive analysis is typical in First Amendment cases: it tries to avoid abstract justifications for violating constitutional rights by forcing consideration of how objectives of legislation would be met by more freedom respecting alternatives.

Fried also objects to Shelby County v. Holder, which struck down preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Court’s decision there pivoted on Congress’s reliance on three-decades-old information to determine which states should be burdened by preclearance. It was Congress’s failure to provide relevant data that doomed the statute. The abstractions of which Fried claims in these cases are illusory: it is his own claims that are abstract and without sufficient reference to the particulars of the cases decided.

But even worse is Fried’s own criterion for determining whether settlements that he admits may not be legally “coherent” should survive. The question for Fried is whether constitutional law needs to be altered to respond to “changed circumstances.” Fried determines for himself that change is not needed on these issues. But shaping constitutional law according to justices’ or commentators’ view of the good consequences is the essence of living constitutionalism. It transfers policy determinations to a small group of unrepresentative individuals. Has conservatism come to this?

And Fried does not criticize Obergefell v. Hodges, but the decision creating a constitutional right to same-sex marriage most obviously changed by judicial fiat a long standing settlement — one that had lasted for hundreds of years in the United States and many more elsewhere and was itself a decision against precedent. Whatever else may be said about the merits of that ruling, it can hardly be called consistent with conservatism. Fried’s failure even to address Obergefell shows yet another problem with his defense of conservatism. It will condemn conservatives to support precedents that are unsound in law, while liberals remain empowered to eliminate precedents that do not cohere with their own abstract theories of justice. For these reasons, Fried’s conservative constitutionalism is a one-way road leftward.