A report of the National Conservatism Conference in London.

Something Rotten in Denmark

Mark Twain thought travel “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow mindedness,” but the much earlier Irish politician and writer Robert Molesworth (1656-1725) noted that it depended on whether visitors brought a discerning perspective to what they saw. Polished, affluent societies, he warned, could “dazzle the eyes of most travelers and cast a disguise upon the slavery of those parts.” Molesworth had in mind the splendor of Baroque France and Spain his countrymen encountered on their grand tour of Continental Europe, but elite reactions to China’s technology and growth today show how despotism can be alluring. Informed judgment, however, could pierce such first impressions to make travel “a great antidote to tyranny.” Observing the conditions of other societies, Molesworth believed, provided a useful point of comparison to better understand one’s own country’s strengths and vulnerabilities. Like studying history, travel could help transcend the limits of immediate experience.

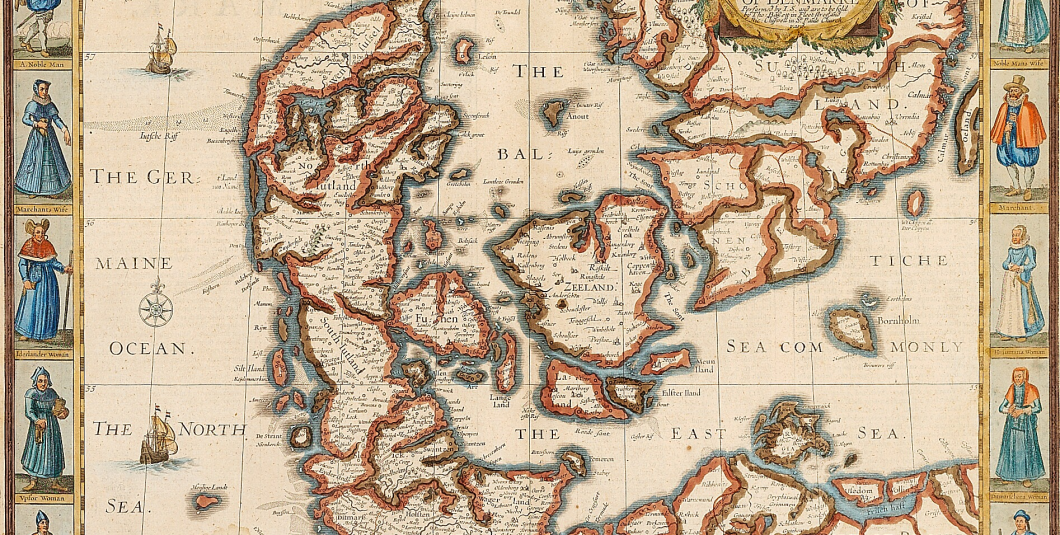

Molesworth wrote An Account of Denmark in 1694 to show how subverting constitutional liberties made a free government despotic. He framed events there during the 1660s as a case study in subordinating nobles, clergy, and commons to hereditary monarchy. Serving as English ambassador to its court from 1689 to 1692 gave him firsthand perspective on the result. What he considered the fragility of England’s political order after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 sparked Molesworth’s warning that corruption poisons the commonwealth much as disease sickens the human body. Comparative study helped diagnose the malady in politics as in medicine to avoid or treat it. He published in 1711 a translation of Francis Hotman’s Francogallia (1573), which traced the free constitution France originally enjoyed before kings usurped power with nobles and clergy. Both works highlighted the danger of losing freedom by degrees so friends to liberty could act in time.

Eighteenth-century booksellers advertised the two works together and bound them into a single volume. David Womersley’s 2011 Liberty Fund edition also combines them as a single text with a scholarly introduction by Justin Champion. The preface to Francogallia, excluded from the original edition for its provocative tone, appeared later as a separate pamphlet entitled “The Principles of a Real Whig.” As Womersley points out, its analysis of variants of “True Whiggism,” has become a standard tool for understanding 18th-century British political thought. Caroline Robbins locates him as the center of a group of Old Whigs often describes as Commonwealthmen. The Liberty Fund edition offers the opportunity to take another look.

Molesworth and Whig Principles

Born in Dublin, the son of an Englishman who made a fortune provisioning Oliver Cromwell’s army, Molesworth grew up in Ireland and attended Trinity College. Few details remain of his early career, but during James II’s reign, he fell afoul of the king’s efforts to build a Catholic interest there to recover lands alienated to Protestants. The Irish parliament in May 1689 attained Molesworth, who fled to England and confiscated his considerable estate. Loyalty to William of Orange secured him the ambassadorship to Denmark, but he lacked the tact and discretion a political career required. Molesworth served in both the English and Irish parliaments but never held prominent office. Charm and literary talent, however, made him a leader among “Real Whigs.”

What then is a Real Whig? Molesworth defined him in the preface to Francogallia as “one who is exactly for keeping up to the strictures of the true old Gothic Constitution, under the three estates of King (or Queen) Lords and Commons” with executive power entrusted to the crown while accountable to the whole body of the people. “Executive power has as just a title to the allegiance and obedience of the subject,” Molesworth writes, “as the subject has to protection, liberty and property.” Loyalty means obedience to the law, not to the will of a prince. Defending toleration, Molesworth calls forcing anyone’s conscience to a standard of our own was “no less a piece of tyranny than that of Procrustes the tyrant of Attica” who was famed for chopping short or stretching out guests to fit the measure of his own bed.

Molesworth persistently rejected associating “commonwealth” with the anarchy and confusion of the mid-17th century civil wars and sought to reclaim the term for a government framed to promote the good of the whole people. Blaming those conflicts on Charles I and royalists, he lay responsibility for their evil consequences entirely on what he called the wrongful aggressor. Never, despite acknowledging Lord Clarendon’s argument to the contrary, did Molesworth see the English people taking up arms except to protect “their liberties and true constitution.” He stood with the parliamentarians who led the Commonwealth before Cromwell brushed them aside in 1653. A contractual view of government, opposition to clerical authority, and insistence on the right of subjects to resist unjust rulers echoed Algernon Sidney. Molesworth looked to clarify principles vindicated in 1688 and refurbish Whig ideology to match them. Defending the Gothic constitution and showing how it had fallen elsewhere served that end.

The men who contrived this absolutist revolution enjoyed financial rewards, leaving the people “the glory of having forged their own chains and the advantage of obeying without reserve.”

An Account of Denmark

Since learning in England valued style over judgment, Molesworth feared education left young men too easily misled by refinement and thus unable to appreciate the misery of societies that had forfeited their liberty. They needed to see that misfortune abroad clearly to value liberty at home just as “Spartans exposed their drunken servants to their children, to make them love sobriety.” Denmark, which lacked the glamor of Louis XIV’s France, offered a valuable lesson in how its nobles and commons gave up their liberty.

Molesworth described the original constitution of Denmark as a limited, elective monarchy Goths and Vandals had established in late antiquity. The first parliaments developed from assemblies of the people that chose and removed kings who lived much like regular nobles on the revenue from their own lands rather than taxes on the realm. Things changed in 1660 when the difficult transition to peace from a costly war threw the country into turmoil. Calling the estates to meet only brought more conflict when nobles sought to widen their privileges beyond immunity from taxes. Clergy and commons—the other two estates—resented those efforts and sought to curb them by offering the king unlimited power with a hereditary crown. At worst, they would have but one master and company in sufferings. Clergy aimed to become partners with the king and thereby free themselves from aristocratic control. Few then knew that courtiers had guided them behind the scenes to set the estates against each other for the crown’s advantage. The nobility tried to delay by seeming to approve what they could not hinder, but, with commons, clergy, and the army against them, they failed to break the plan’s momentum. Had they showed even a little courage, Molesworth thought they might have prevailed as the king would not have forced the point. Instead, all swore an oath of allegiance to a newly absolute monarchy.

The men who contrived this revolution enjoyed financial rewards, leaving the people “the glory of having forged their own chains and the advantage of obeying without reserve.” Never mentioned by name, the king had a mild temperament and subjects later blamed their misfortunes on what he permitted rather than what he did. Molesworth found the system and not the ruler at fault, and linked Denmark’s poverty with the insecurity of property and high taxes. Living standards were lower in a hand-to-mouth economy. Parsimony, he argued, both reflects and causes riches since husbanding them builds a larger stock, but the insecurity of wealth promotes improvidence. Denmark lacked the prosperous yeoman farmers he called England’s strength. Its nobles and merchants were far less affluent than their English counterparts. The lack of wealth retarded belles lettres and learning, though “the common people do generally read and write.” A legal system whose simplicity makes justice available quickly and at low cost in contrast with England struck the only positive note.

Molesworth stressed French influences on Denmark in taste and political thinking—the latter reflected by a large army of troops recruited abroad and the belief that soldiers marked a nation’s wealth—but also noted the country’s protestant culture. Englishmen made a great mistake in thinking Catholicism was the only sect to uphold despotism. “Other religions,” he wrote, “and particularly the Lutheran, have succeeded as effectively in this design as ever Popery did.” The authority clergy held over conscience made them effective partners in tyranny. Molesworth saw the Lutheran clergy’s desire to free themselves from aristocratic patrons as a key factor in Denmark’s subjugation. It became a central lesson he drew from the story.

The Gothic Constitution

Representative institutions had been common in Europe under various names until rulers largely dispensed with them in the 16th century. England’s parliament marked an exception in an age of bureaucratic absolutism, and the Whig historian John Oldmixon claimed in 1724 that “no nation has preserv’d their Gothic constitution better than the English.” Despite the Glorious Revolution, Molesworth feared the same threat as in Denmark. Showing how popular assemblies predated kingship and had legitimacy apart from it became essential to defending them.

Hotman’s Francogallia offered France, with Merovingian kings and bishops conspiring against liberty, as an example that paralleled Denmark’s later experience. A humanist and legal scholar exiled for his Calvinist beliefs, Hotman deployed a wealth of material to sketch the political order that Germanic tribes carried into the post-Roman west. Assemblies of the people selected and often deposed rulers. Patrimonial estates of kings which descended by inheritance were also separate from the realm itself. Sovereignty rested with the public council of the nation rather than, as Jean Bodin later claimed, the king. This justified resistance to rulers who exceeded their authority. Indeed, Hotham lamented the usurpation by churchmen and nobles who joined kings in subverting the Gothic constitution and made the commonwealth into a realm where royal control only became stronger.

Molesworth’s translation in accessible English reframed Hotman’s resistance theory for 18th-century readers. Historical contingency made traditions of freedom vulnerable and defending them effectively required understanding both how they worked and the processes by which they were subverted. Francogallica reinforced the Account of Denmark which had made that realm a byword for despotism. Louis XIV’s bureaucratic absolutism and recent persecution of the Huguenots highlighted the dangers felt even after the French bid for European hegemony faltered in the War of Spanish Succession. Molesworth, after all, wrote for an Anglophone readership to warn liberty in the British Isles could suffer the same fate.

Influence and Legacy

Despite his best efforts, Molesworth remained an opposition figure with the 1720 ascendancy of Court Whigs that he had despised keeping him on the margins. His outlook remained stuck in the 1690s. Hurt financially by the South Sea Bubble, he fiercely criticized the company and speculators who created it. Monied wealth easily left the country, whereas land and other property owners were tied to the commonwealth. Elected rector of Glasgow University in 1721, Molesworth left parliament and spent his final years in Ireland. His influence rested on writings and a circle of prominent intellectual friends including John Toland, Walter Moyle, and John Gordon. Court Whigs like Sir Robert Walpole and his successors the Pelham brothers had little use for their arguments, especially as contract theory and the right of resistance fit awkwardly with upholding the Hanoverian Succession against Jacobitism. The Gothic constitution also fell out of favor in the 1720s as medieval precedents resonated less in Georgian Britain. David Hume’s widely read History of England challenged the antiquity of a political order that the Scot had dated largely to 16th-century developments.

Molesworth still provided rhetorical ammunition that lingered in 18th century thought. Thomas Holles included his works among the volumes he sent to the American colonies where they influenced critics of British policy from the 1760s. Bernard Bailyn cites John Adams and Moses Mather as among those who drew on his ideas, though printers in the colonies did not publish editions. Opposition Whigs in England, including friends of John Wilkes brought them back into circulation and they shaped an emergent radical tradition. The fact that his thinking resonated suggests it reached beyond Molesworth’s time and place, but it appealed mainly to opposition figures. Men who sought arguments and rhetoric to fight insiders found his critique more useful than those who exercised power or looked to uphold the common good. Court Whigs and even Tories, as experience over the 1700s showed, addressed the challenge of governing more effectively than Molesworth and his friends. And that distinction showed the limits to their influence.