From whence cometh our help?

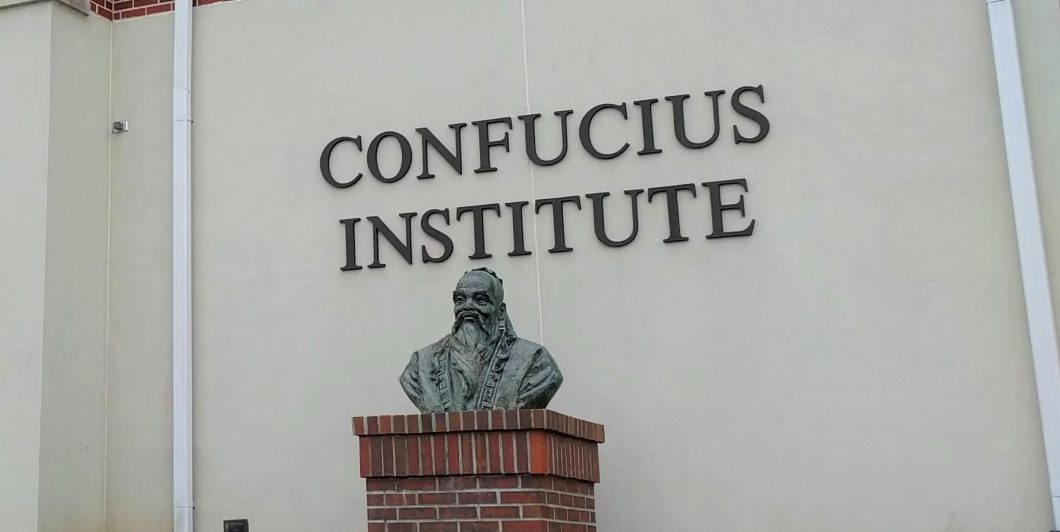

Confucius Institutes: China's Trojan Horse

When the Left and the Right agree on something in these disputatious times, the wise man will want to know what it is. And what has brought these warring factions together, however briefly? The Confucius Institutes that dot American campuses.

The progressive New Republic magazine and the conservative National Association of Scholars (NAS) both warn that the Institutes are not the innocent cultural centers offering Chinese language instruction they pretend to be. They are, rather, a key stratagem of China’s “soft war” against America, crafted, in the words of NAS senior researcher Rachelle Peterson, to “teach political lessons that unduly favor China.”

Writing in the New Republic, Isaac Stone Fish referred to “an epidemic of self-censorship at U.S universities” that funnels students away from “topics likely to offend the Chinese Communist Party.” Topics like the disastrous Great Leap Forward from 1958-1962 that enforced collectivization in the towns and countryside and resulted in the deaths of 30 to 50 million Chinese.

China’s use of “hard power,” such as its aggressive weapons buildup, its suppression of free speech and assembly in Hong Kong and throughout the mainland, its stern warnings that Taiwan must not chart an independent course, and its colonization of the South China Sea, draws the headlines and attracts the attention of policymakers. Meanwhile Confucius Institutes, financed by the Chinese government and supervised by the Chinese Communist Party, are molding attitudes about China, painting an idyllic portrait in which Mao Zedong is a revolutionary hero and the Tiananmen Square massacre never happened. That the Confucius Institutes are instruments of propaganda was confirmed by Li Changchun, the head of propaganda for the CCP, who boasted that the Institutes were “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda setup.”

Founded in 2004, the Confucius Institutes are a global phenomenon, enrolling more than nine million students at 525 institutes in 146 countries and regions. More than 100 institutes have opened in the United States, including at prestigious universities such as Columbia and Stanford. They are mostly staffed and funded by an agency of the Chinese government’s Ministry of Education—the Office of Chinese Languages Council International, or Hanban. The Hanban also operates Confucius Classrooms in an estimated 500 primary and secondary schools in the United States.

A 243-page NAS report described in detail the many strings attached to the goodies offered by Confucius Institutes:

Intellectual freedom. Chinese teachers—hired, paid by and accountable to the Communist Chinese government—are pressured to avoid “sensitive” topics like the Tiananmen Square Massacre and the Cultural Revolution.

Transparency. Contracts between American universities and the Hanban are rarely made public. One university went so far as to forbid Rachelle Peterson from visiting their campus as part of her research.

Entanglement. Confucius Institutes cover all the expenses of classes and also offer scholarships to American students to study abroad. With such financial incentives, universities find it difficult to criticize Chinese policies like its genocidal treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Western China.

Soft power. Confucius Institutes avoid discussing China’s widespread human-rights abuses and present Taiwan and Tibet as undisputed Chinese territories. As a result, writes Peterson, the institutes “develop a generation of American students with selective knowledge of a major country”—and a major adversary. Confucius Institutes are a textbook example of soft power that causes universities in receipt of Chinese largesse to stay silent about controversial subjects like China’s use of forced labor to pick cotton, a 21st century variation of the slavery of the ante-bellum South.

The Confucius Institutes pretend to be a Chinese version of cultural institutions like the Alliance Française or the Goethe Institute, but they are in reality a propaganda machine funded and directed by the Chinese government. Based on the findings of its 2017 report, the NAS recommends that “all universities close their Confucius Institutes.”

Writing in the New Republic—the leading journal of the Left—Isaac Stone Fish said he had found on many American campuses “a worrying prevalence of self-censorship regarding China.” Some of America’s most distinguished schools kowtowed to Communist China, including Columbia University’s Global Center in Beijing, which cancelled talks “it feared would upset Chinese officials.” North Carolina State University canceled a visit by the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s revered religious leader. The university’s pragmatic provost explained his decision with the revealing statement that, “China is a major trading partner for North Carolina.”

Academic self-censorship has an impact far beyond the ivy tower, Fish points out. It restricts the ability of U.S. policymakers, business leaders, human-rights advocates, and the general public to make the right decisions about how to interact with China. For the Hanban, the correct decision is one that acknowledges China’s rightful place as the Middle Kingdom of Asia and a global superpower as important as the United States.

Leading American universities are not immune to China’s hard-edged soft power. Minxin Pei, a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and an open critic of China’s authoritarian government, refers to the American institutions that have programs in China as “hostages.” “If you’re Stanford or Harvard and you have operations in China,” Pei asks, “are you going to host a famous dissident?”

The question of self-censorship is a proxy, argues Fish, for the critical question of how to react to the global rise of China. Should the U.S. protest it? Accede to it? Try to stop it? Regardless of the reservations of liberal U.S. academics about American global dominance, he says, “many China studies professors have spent enough time in China to conclude they don’t want to live in China’s world.” American academics should think critically, he says, about “how to respond to China’s growing influence instead of acting as [President Jinping] Xi’s willing censors.”

China’s dissemination of what amounts to communist propaganda on American campuses has attracted the attention of U.S. senators and congressmen across the political spectrum. Sen. Robert Menendez (D-NJ) referred to China’s “tentacles of influence,” such as the Confucius Institutes, the setting up of CCP cells in U.S. businesses, and espionage targeted at high-tech research. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) expressed concern about the Chinese government’s aggressive attempts to use Confucius Institutes to influence critical analysis of “China’s past history and present policies.”

A bipartisan group of Senators ranging from Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) to Ted Cruz (R-TX) called out “those that seek to suppress information and undermine democratic institutions and internationally accepted human rights.” Sens. Rob Portman (R-OH) and Tom Carper (D-DE) asserted that absent full transparency of operations in the U.S. and full reciprocity for U.S. college in China, “Confucius Institutes should not continue in the United States.”

If scholars are found guilty of incorrect classroom content or publications, their families in China are threatened, and they are banished from returning to China.

U.S. intelligence agencies joined the chorus of concern, led by FBI Director Christopher Wray, who revealed that the Bureau was monitoring the activities of the institutes closely. As of this April, there were 47 Confucius Institutes in the U.S., down from a high of just over 100, led by Columbia, Stanford, UCLA, Rutgers, and George Washington University. There were also Confucius Classrooms in seven K-12 school districts. Many of the CI closures occurred in 2018 when Congress passed legislation forbidding schools with Confucius Institutes from receiving language funding from the Defense Department. Almost immediately, 22 schools closed their Confucius Institutes.

The University of Chicago shut down its institute after 100 professors signed a petition citing the “dubious practice of allowing an external institution to staff academic courses within the University.” A University of Chicago professor called the Confucius Institutes “academic malware” injected into the university system. In response, Hanban attempted American-style rebranding, changing its name from Hanban to the Ministry of Education Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation. It created a separate organization—the Chinese International Education Foundation—which will fund and oversee Confucius Institutes.

But the raison d’etre remained the same—to present a carefully sanitized story of a powerful aggressive China. The 90 million members of the CCP are dedicated practitioners of Marxist-Leninist-Maoist-Xi thought as set forth in a recent document of the CCP’s Central Committee. It warns officials across the country, including those who manage the Confucius Institutes, to be fully alert to the threat of certain Western ideas, known as the “Seven Don’t Speaks”: universal ideas; freedom of speech; civil society; civil rights; historical errors of the CCP; official bourgeoise universal ideas; and judicial independence.

These “Don’ts” are a checklist for scholars who study in or about China. If they recognize them as threats to “Communism with Chinese characteristics” and exclude them from their classes and publications, well and good. But if they are found guilty of incorrect classroom content or publications, their families in China are threatened, and they are banished from returning to China.

According to Lucy Hornby of the Financial Times’s Beijing bureau, China has long used the real or imagined benefits of “access”—such as visas, research cooperation, and the “honor” of being met at the Purple Light Pavilion in the Imperial City in Beijing by someone who far outranks you—to obtain acquiescence and/or silence on “red line” issues like the Three T’s: Taiwan, Tibet, and Tiananmen.

Regardless of their brand, reports Peterson, Confucius Institutes will fulfill the Chinese government’s goal of maintaining outposts on American college campuses “where they can disseminate propaganda, conduct espionage, monitor overseas Chinese students, and advance the [government’s] agenda to ‘make the foreign serve China.’”

In acknowledgement of the Institutes’ threat to academic freedom and opposition to telling the truth about China’s persistent violation of human rights, the Trump administration proposed that American colleges and universities be required to disclose any financial ties with Confucius Institutes. (Some schools accept as much as $1.7 million annually.) Despite the bi-partisan criticism of the Institutes, the Biden administration withdrew the Trump proposal—sending a global signal that, in Peterson’s words, “the Biden administration will not take Confucius Institutes seriously.” The Biden White House should talk to FBI Director Wray, who takes the Institutes very seriously.

Over 2,000 years ago, besieging Greeks tricked their way into the city of Troy with the gift of a giant wooden horse within which they hid solders who, while the Trojans were celebrating a victory, opened the gates and let in the rest of the Greek army. Ever since, we have been told, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.” The Confucius Institutes are the modern equivalent of a Trojan horse, seemingly benign and apolitical, but committed to shaping our understanding of an authoritarian adversary out to undermine America’s leading role in Asia and around the world.