Preserving good government depends upon a people’s ability to demonstrate the character appropriate to the task—and ours is in question.

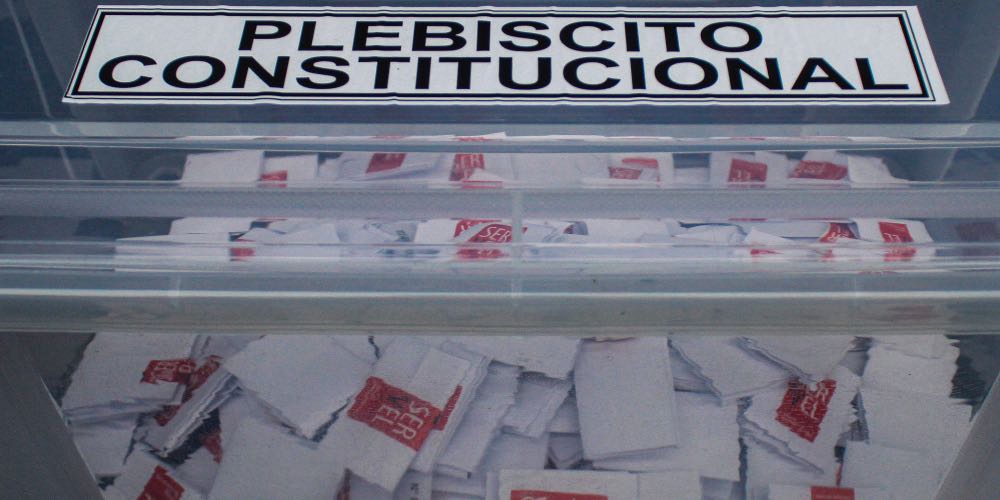

Constitutional Chaos in Chile

Last month, Chileans went to the polls resoundingly to reject a proposed new constitution for their republic, with 62% of the electorate in opposition. To an outside observer, this might seem puzzling. Just two years ago, the country voted heavily to hold the convention that wrote the proposed new constitution the public just rejected. The short explanation is that the convention did an abysmal job, confecting a document rife with contradictions. To get an idea of what might happen next, it’s worth going into a bit more detail about why the public sought a new constitution.

The left has long wanted to rewrite Chile’s constitution. In 1970, when three presidential candidates split the vote, Salvador Allende came first with just under three-eighths of the vote. Throughout his time in office, Allende sought a new constitution that would free him to act as he pleased, but before that could happen, he lost the struggle to control the armed forces, and was deposed in a coup, followed by almost seventeen years of authoritarian rule.

Chile is known as a legalistic society, with paperwork and receipts for everything. Even the military government decided to put forward its own constitution. Drafted by a panel of legal experts, the Ortuzar Committee, the even-handedness of the proposed constitution displeased then-Dictator Augusto Pinochet, so he set his aids to work making modifications. Written and then approved in a rigged 1980 referendum, these changes centered on a brace of now-expired transitory articles that expanded Pinochet’s powers and delayed until the end of the 1980s the return to democracy. In a now famous sequence of events, Pinochet lost a 1988 plebiscite on whether he would be given an additional eight-year term, and during the subsequent transition the military government and the civilian opposition negotiated a set of amendments to the constitution that in 1989 were put to an honest referendum, in which they were approved. Pinochet was replaced by a democratically elected president in 1990, and since then the constitution has been regularly amended, most recently on March 11, 2022. Today’s document is not the charter Pinochet pushed through in the tainted 1980 referendum.

A great deal has been written about Pinochet losing power in 1988 within the framework of his own constitution. The reality is that the constitution, with its framework for democratic restoration, was the price he had to pay to remain in power. Sergio Diez, a member of the Ortuzar Committee, claimed that it “is impossible to construct a socialist state” within the current constitution. The left seem convinced he was right. Since Chile’s 1990 return to democracy, the left has continued to seek a constitution along the lines wished for by Allende.

In 2016 President Michelle Bachelet, a Socialist elected at the head of a broad left-of-center coalition, renewed the push for a new constitution. She convened a set of town meetings around the country seeking input about what people would like to see in a new constitution. Like a “push poll” the meetings were not so much designed to gauge public opinion as to shape it. The sporadic feedback from these meetings seems never to have been systematically analyzed. Bachelet’s initiative marked the beginning of the current campaign to abolish Chile’s present Constitution.

Many on the left believed that there was a “silent majority” of low income voters who would support leftist policies if they could only be brought to the polls.

The left is eager to replace Chile’s current constitution with a document more similar to the constitutions of Bolivia and Venezuela. Partly, this is because of the subsidiarity principle embedded within the current constitution. Former president Ricardo Lagos recently singled this out as his central criticism of the status quo charter. Lagos noted that when Argentina cut off Chile’s natural gas supply he had to collaborate with the business community to find alternative emergency supplies on the world market; he would have preferred to have been able to give them orders. Of course, his example is telling—few things unite Chileans like their shared appreciation for their neighbors on the other side of the Andes Mountains, and a solution to the gas shortage was quickly worked out. When everyone is on the same page the institutions are a matter of form rather than of substance. The subsidiarity of the constitution and its recognition of individual rights and of private property are more consequential when the public is divided.

In 2018, Michelle Bachelet was succeeded by Sebastián Piñera at the head of a right-of-center coalition. When political street violence erupted on the eve of the Covid epidemic the Chilean Communist Party demanded a referendum on whether to hold a constitutional convention, and so in October 2020, amid the pandemic and with voluntary voter participation, the electorate opted by a resounding 56% margin to hold a constitutional convention to write a new constitution. Many on the left believed that there was a “silent majority” of low-income voters who would support leftist policies if they could only be brought to the polls. They held out for, and got, the stipulation that the proposed constitution would be put to an up or down vote in a plebiscite, with mandatory voter participation. But first, there was the matter of electing the convention delegates.

Ever since 1990, a key implement in the legislative toolkit of the Chilean right has been to gather enough votes to block bad ideas. The rules for the convention specified a two-thirds threshold for adopting text, allowing a minority coalition of a third plus one of the convention delegates to stop measures from going forward. As it happened, the right was overly optimistic about how well its candidates would fare at the polls, while the Communists were surprisingly successful in gaining heavy representation among the seats reserved for indigenous candidates. The result was a convention in which the seat share of the right constituted less than a third of the delegates, leaving them without their customary ability to block measures they didn’t like, while the more numerous Communist-indigenous bloc of delegates did wield a de facto veto. Mostly absent from the convention were politicians from the center-left coalition that had held power for the bulk of the preceding three decades. Instead, the larger part of the remaining delegates were amateur politicians imbued with the dilettantish notion that compromise is tantamount to betrayal of one’s principles. The result was a document consisting of 388 articles, plus 57 transitory articles, chockablock with incompatible and extreme measures.

The proposed constitution defined the people of Chile as being made up of “diverse nations,” with citizens having fundamental individual rights while indigenous peoples additionally were to have collective rights. In a bow to environmentalists, “nature” also was to enjoy certain inalienable rights. In addition to violating the principle of equal treatment under the law, the special status established by the proposed constitution would have exposed fatal ambiguities about who was indigenous, as most Chileans have at least some pre-Columbian American ancestry. The same constitution that demanded that all have equal rights also mandated that women comprise at least fifty percent of personnel in all state organizations—it was permissible to have more, but not less.

Refugees from the “Bolivarian Republic” are everywhere in Chile, a pervasive reminder of the possible consequences of electing the hard left.

This fundamental document would have given international agreements the force of constitutional law. Articles 151-158 made ample provision for popular initiatives at all levels of government, and for popular voting to reverse pieces of legislation. Article 201 would have established a series of ”autonomous” communities, formed on the basis of “demographic, economic, cultural, geographic, socio-environmental” criteria, as well as the level of urbanization, empowered with “the autonomy to fulfill its functions and to exercise its competencies”—a godsend for narcotics dealers. The proposed constitution would have severely weakened the Senate, creating what would have amounted to a unicameral legislature. There was also a grab bag of over a hundred unenforceable articles guaranteeing rights to everything from a clean environment to digital education. Taxes would have to be progressive, ruling out both value added taxes, and per-gallon gasoline taxes. With enough computing power, perhaps the government could have means-tested consumption taxes. A reader could spend endless hours encountering contradictions among the hurrah’s nest of articles set forth in the proposed document. In practice the judiciary would have had to resolve the contradictory tangle of rights and entitlements, leaving people to guess how the particular magistrate confronting their case would rule. This is precisely the sort of ex-ante uncertainty a well-functioning legal system is supposed to preclude.

Once unveiled, the proposed constitution encountered predictable criticism from the right, but also, on the basis of its many internal contradictions, from many voices of the center-left. Nevertheless, many others took the stance that the country had voted for a new constitution, and so a new constitution it would have, with the design flaws to be resolved later.

As Chileans went to the polls, opinion surveys indicated it would be a close decision. It was not. When the blizzard of ballots from the mandatory plebiscite was tallied, five-eighths voted to reject, while a mere three-eighths—the same fraction won by Allende a half a century earlier—voted to accept the new constitution. More people voted to reject in the mandatory plebiscite than had voted at all in the referendum on whether to call for a convention.

There were surprises in the variation of votes across Chile’s nearly 350 municipalities. Only eight gave a majority of their votes to the proposed constitution. More surprisingly, when they divided municipalities into income quintiles, researchers Miguel Angel Fernandez and Eugenio Guzman of the Universidad de Desarollo found that the lower a township’s income, the wider the margin by which it rejected the proposed constitution! Sorted by the fraction of people identifying as indigenous, the greatest opposition was to be found among the bottom and top quintiles. Given the special considerations accorded to indigenous groups in the constitution, it is perhaps not a surprise that the bottom quintile was not attracted to the proposed constitution, but this antipathy also emerged among the communities with the largest fraction of the indigenous population! Perhaps it was the prospect of further empowering the self-styled indigenous elite that they found unappealing—arson and violence directed against those disliked by the local indigenous leaders have become commonplace in rural southern Chile.

What will happen next? Even as the final ballots were being counted, Chile’s newly elected President Gabriel Boric took to television to announce his support for a second convention. There will be more constitutional reforms, either in the form of a packet of amendments to the existing document, or presented as a new fundamental law. Many Chileans are deeply apprehensive that the parties of the left will convert their country into a recycled version of Nicolas Maduro’s Venezuela. Refugees from the “Bolivarian Republic” are everywhere in Chile, a pervasive reminder of the possible consequences of electing the hard left. The Boric government’s ostentatious approval of the region’s left-wing totalitarian governments only intensifies the public’s concerns.

Campaigning in the shadow of the Constitutional Convention, Boric was elected promising to serve as a transitional president who would manage the handover to the new constitution. Now he finds himself in an Uber, coming back from the airport, Chile’s flight to Venezuela having been canceled by the voters. He has three and a half years of his term ahead of him. President Boric has tacked slightly toward the center. After the plebiscite he reshuffled his cabinet, giving more prominent positions to Socialists and diminishing the profile of the Communist Party. In his post-plebiscite speech to the UN, Chile’s head of state included some belated solidarity for political prisoners in Nicaragua, and after having just the week before rejected the credentials of the Israeli ambassador, he affirmed the right of the Levantine republic to exist. It will take a lot more to convince the public that a new Constitution written to please his coalition partners in the Communist Party, won’t leave the voters trapped in an Andean version of Venezuela.