Deindustrialization's Global Story

Almost two centuries ago, Alexis de Tocqueville, the great observer of American democracy, argued that two nations of the world—Russia and America—were starting at different points but progressing towards the same ends—power, wealth, and influence. After World War II, both nations achieved superpower status but in very different ways. While Russia chose the path of illiberalism—first under the Romanov dynasty and later the Communist Party—America became the world’s freest and most prosperous liberal democracy in history. This is the “just-so” story we tell ourselves about ourselves: neat, tidy, and unambiguous.

Beneath this “just-so” story of difference, there is an overlooked story of similarity. In the last half-century, certain communities and peoples within each nation have suffered through wrenching economic change due to the economic fallout of deindustrialization and consequent workforce dislocation. In the case of the UK and US, the effects of automation and globalization were associated with a shift towards service industries which left many workers ill-prepared for new employment. In the East, the fall of the Soviet Union wrought even deeper economic dislocation, forcing an overnight revolution in Russia’s government and a wildly distorted and inefficient state-run economy. In all three cases, industries such as heavy manufacturing and mining that once anchored economic and social life disappeared or collapsed in a relatively brief period. Many of the regions, communities, and towns that bore the brunt of concentrated economic dislocation and social upheaval have still not recovered.

Across these deindustrialized places, the similarities are more common than is generally acknowledged, or than we’d like to admit. This geopolitical, social, and economic story of commonality is told by Brookings Institution scholar Fiona Hill in her recent book, There is Nothing for You Here. Growing up a coal miner’s daughter in the northern England rustbelt, by dint of personal determination and effort, she overcame economic, class, gender, and cultural discrimination to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard and become a leading expert on U.S.-Russia relations.

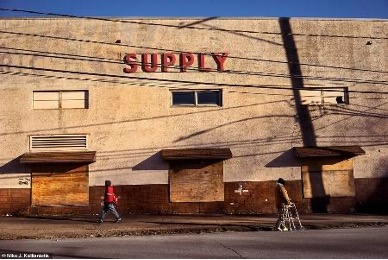

Walking through the streets of these once-thriving communities, Hill says, feels almost identical despite the geographic, historic, and political distances. The abandoned coal mining or manufacturing towns in the American Rustbelt, the Russian Urals, or the north of England have strikingly similar architectural and social environments. The resemblances can be jarring and uncanny.

These communities tend to look a lot alike beneath the surface as well. In all three nations, sudden workforce dislocation is associated with substance abuse (opioids in the U.S., alcohol consumption in Russia), lower life expectancies (in parts of Russia as low as 45 years), and a hopelessness that has hardened into anger, resentment, and political alienation. Traditional economic theory predicts that dislocated workers will relocate to prosperous areas or retrain. But even in the U.S., with its free markets, history of geographic mobility, and entrepreneurial spirit, people who lost jobs and careers to automation and trade have largely remained within their communities.

Part of this geographic immobility is the result of tightly bonded cultures that were built around once vibrant core industries. Qualitative studies of ex-mining regions of the U.S. find that the conception of self and community is historically tied to the industry: mining as a means of survival, connection with community, personal identity, familial relations, and cultural identity. In other words, work was not the only thing—and perhaps not even the most important thing—that working-class communities lost when the jobs went away.

When dislocation happens in democracy, the social alienation that accompanies economic change and cultural stress often fuels political unrest. Economic grievances in dislocated communities tend to meld with cultural anxieties, according to the analysis of Harvard Professor Pippa Norris, and with social and community decay, according to AEI’s Tim Carney. This melding fosters “us-versus-them” resentments that are then reflected in political attitudes and voting behavior.

The connection between economic distress and political populism isn’t new. Throughout American history, times of economic stress, depression, and transition have correlated with rises in economic grievances and interrelated social and cultural conflicts. This was the case during the agrarian discontent of the 1870s industrial revolution, and the populism that marked the unemployment and destitution of the Great Depression.

Deindustrialization across the globe has similarly exacerbated social and political tensions globally today, from the rise of Vladimir Putin in Russia, to the UK’s abrupt Brexit from the European Union, to the election of Donald Trump, along with analogous developments in France, Hungary, Poland, and Germany, among others. While the U.S. has thus far avoided the most extreme political outcomes, failing to come to terms with the anger and despair wrought by economic hardship, Hill says, risks social and political danger. We are not Russia—yet. But if we don’t adjust, Russia may come to be seen as “America’s ghost of Christmas future.”

While the correlation between dislocation, economic distress, and political discontent is clear, it also risks veering into another “just-so” story, a little too neat and deterministic. Alongside apparent bottom-up similarities between Russia and the West in their journey through deindustrialization, there are also stark bottom-up differences rooted in disparate histories, cultures, and political systems. Similar recent problems do not guarantee they will reach the same end results.

All three countries passed and are passing through similar economic transitions, but have coped (and are coping) with deindustrialization through different cultural matrices of history, politics, economics, and, crucially, commitments to democratic values. In the cases of the US and UK, democratic political mechanisms have (somewhat imperfectly) absorbed, ameliorated, and redirected the forces of dislocation. As AEI’s director of foreign and defense policy studies, Kori Schake, pointed out in a recent AEI event on Hill’s book, the American people have a history of indulging populist impulses while keeping them on a short leash through vigorous and critical public exchange.

While the U.S. has been remarkably successful in dampening the impacts of deindustrialization, our policy responses over the past few decades have also been, in too many places, too little, too late—and sometimes they didn’t arrive at all.

For instance, when economic distress hit American farmers in the 1870s and 1880s, William Jennings Bryan’s People’s Party sought to protect agricultural interests, railing against industry and urbanism. Bryan was unable to assemble a majority in three presidential races because his populist message lacked broad enough appeal. Nonetheless, the ideas he championed, including the graduated income tax and eight-hour work day, would continue to have influence and even triumph in policy history. Similarly, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal softened the impact of the Great Depression and helped to ease the social pressures and populism it generated. Russia, on the other hand, lacking significant history in liberal democracy and political mechanisms for responding to social stress, has fallen back on its history of political repression and economic royalism and exploitation.

Free people in a free economy have a remarkable capacity to weather dislocation and adjust over time. While dislocations associated with deindustrialization are facts of life in regions of the country, these conditions are the exception rather than the rule of the U.S. economy. According to one Brookings study, over two-thirds of the older industrial cities hit by deindustrialization have transitioned successfully from manufacturing to other forms of industry and employment. Despite dislocation, wages and output continue to increase, and unemployment since the 2008-10 recession has been falling. Entrepreneurship remains strong, with Americans filing paperwork to open 4.3 million new businesses even during the hardship of the pandemic.

This American combination of democratic flexibility and economic dynamism means that America has the resources and political wherewithal to adjust and even thrive in the face of the stressful economic transition in a way that an authoritarian society and culture like Russia’s does not. Research from AEI’s director of economic policy, Michael Strain, and Diane Schanzenbach of Northwestern shows that the use of government transfers like the Earned Income Tax Credit and other safety-net programs have softened the blows of dislocation, prevented even more widespread economic hardship, helped increase incomes, and blunted inequality. Viewed this way, much of America’s resiliency derives from its continuing commitment to certain political and social values: respect for individual rights and limited government, free markets, and democratically accountable government. One might say that everything we think of as America’s strengths—family, community, economic prosperity, and opportunity—is downstream from its overarching commitment to liberty.

While the U.S. has been remarkably successful in dampening the impacts of deindustrialization, our policy responses over the past few decades have also been, in too many places, too little, too late–and sometimes they didn’t arrive at all. This brings us to, if not a parting of the ways between political liberals and classical liberals, then to some relatively clear distinctions in the way the center-right and center-left of America look at solving the nation’s economic and political problems.

Political liberals tend to favor more active intervention by government to relieve distressed communities. In her book, Hill argues for a “Marshall plan for America” aimed at fostering place-based regeneration. Embedded in this argument is the idea that an absence of opportunity is what holds individuals and communities back. If government spends public resources to build ladders of opportunity, the argument goes, people will respond in kind. A vicious cycle can, by government action, be replaced with a virtuous one.

To many classical liberals, this sounds uncomfortably like a replay of the “place-based” Great Society and War on Poverty programs which overlooked individual agency and thereby failed to place the individual at the center of policies and programs designed to ameliorate poverty. When “poverty won” and greater shared prosperity failed to appear, public confidence in government intervention collapsed.

While the insights and preferences of political and classical liberals each have their points, this history of socio-economic experimentation suggests the best way to reduce inequality and foster opportunity is to lean into individual and community dynamism that will “grow the pie” from the inside, thereby allowing people to engage in free markets to generate opportunity within each locality, rather than trying to engineer prosperity through top-down programmatic interventions. Guiding growth directly or reaching into communities from the “outside” is not only inefficient but can be counter-productive, deepening political resentment while leaving economic distress unresolved.

Government has a part to play, both by its positive actions and by what it chooses not to do. Both free markets and safety nets are important now and in the future as are policies that promote self-development with a healthy dose of sweat-equity from individuals. Policies that encourage and, in some cases, require workforce participation for those that have dropped out of the labor force should be matched with training and educational accounts that give workers the highest level of control possible over their employment and economic destinies.

The turbulence of the age means we need to keep a weather-eye on the nation’s economic and political outlooks without being apocalyptic about a slide into authoritarianism. Though helpful in shedding light on more complex realities, we, luckily, do not live inside either of the deterministic “just-so” stories we’ve detailed. Instead, we are part of a national story that is being written through the choices and actions of 320 million Americans. Ensuring the resiliency and flexibility of our workforce will ensure that the future need not look like the past. As we experience new challenges to our prosperity, our best course is to rely chiefly on the capacity of free people and institutions to shape and build our future. If we do, there will be something here for everyone.