We need to understand the history of the development of market economies in terms of institutions and culture.

Economists Should Return to Moral Philosophy

Policy makers and economists of various stripes have had a field day since the onset of the last financial crisis blaming the downturn on market failures and proclaiming new regulatory fixes. Never mind that most of the mainstream either did not anticipate the collapse or had even preached perpetual boom, they were brimming with solutions. That fact has set a few members of the economics profession on edge and in one case, has inspired an important new contribution to thinking about markets. What is the right way of conceiving the relation of public policy and law to economics?

Certainly most economists and economic pundits see the utilitarian connection. On the right, this has meant a general disposition in favor of neo-classical style analysis of efficiencies. On the left, it has meant the kind of legal realism that seeks to uncover the underlying interests in social, political and legal frameworks to fashion more equitable social and economic policies. Against these predominant viewpoints is the recent and critical work by economist Enrico Colombatto of the University of Turin and director of the International Centre for Economic Research, in his book Markets, Morals, and Policy Making (Routledge; 2011).

Certainly most economists and economic pundits see the utilitarian connection. On the right, this has meant a general disposition in favor of neo-classical style analysis of efficiencies. On the left, it has meant the kind of legal realism that seeks to uncover the underlying interests in social, political and legal frameworks to fashion more equitable social and economic policies. Against these predominant viewpoints is the recent and critical work by economist Enrico Colombatto of the University of Turin and director of the International Centre for Economic Research, in his book Markets, Morals, and Policy Making (Routledge; 2011).

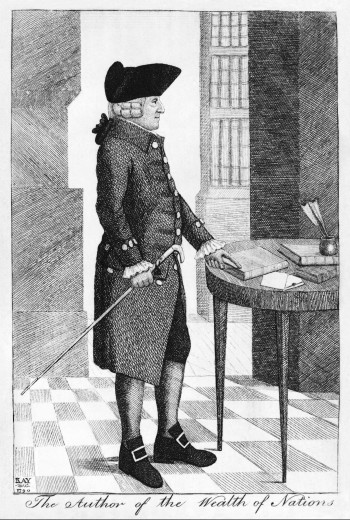

Displaying the erudition and insights of one steeped in the scholarship of both American and European perspectives, Colombatto has developed a powerful argument that economics and public policy must ultimately return to their original foundations (as exemplified, for example, by Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment) in moral philosophy. This notion will not please the majority of economists and policy analysts and the author is well aware of the fact, but it will be difficult for any of them not to take his arguments seriously if they choose to read this work with the care that it deserves.

At the core of Colombatto’s thesis is a basic, disarmingly simple theme, but when confronted directly, gives very little wiggle room for prevarication or fudging. The drive to prescribe economic policies during crisis has laid bare the fundamental tension that rests at the heart of so much recent scholarship. Economists today love to preach the universality of their discipline to all endeavors, often articulating some variation on the idea of opportunity costs to the effect that there are no free lunches or that every decision will always entail tradeoffs. To this our author says fair enough, but then proceeds to illustrate with painstaking attention all the different ways the profession has tried to have its cakes and eat them too. The basic tension stems, on the one hand, from the desire to analyze how things are versus the aim to prescribe how things ought to be. In the realm of policy, most want to blur the distinction without explicitly declaring for one or the other, and that entails a fundamental contradiction, according to our author.

As scientists, economists have generally come to accept the subjective theory of value. Individuals have their own goals and aims and from this fact, they define their own sets of values. Certainly we are all influenced by friends, family and society, but each person’s particular perspective is his/her own unique blend of inputs and inclinations. Markets are the means by which these diverse valuations are coordinated and realized in a free society, and that notion of ultimate subjectivity grounds economics in methodological individualism.

That said, most economists also insist that they can proclaim on the optimality of outcomes, improving on conditions arising from poor information or bad institutions, and that everyone could be made better off if they just took their advice and got the incentives right. That inclination produces a powerful inducement to modeling and formalization, which inevitably result in simplification and the reduction of complex phenomena for purposes of mathematical representation. Invariably, then, the economist or policy maker will assume a static conception of a higher good or some particular end that is socially or politically “given,” rather than individually determined, discounting the degree to which all social outcomes are the product of dynamic individual decisions, entailing individual learning through trial and error over time.

There is then, according to Colombatto, a basic tension between ostensible method and practical application which he argues makes for the uneasiness that most economists feel when dealing with foundational questions of “how they know” (epistemology), and “what they do” (practice). Refusal to confront that tension helps the so-called “experts” to elide the distinction between their politics and their science.

Colombatto would ask them to desist, not simply because they cannot ultimately substantiate most of what they advocate by way of policy, but that such a basic foundational confusion detracts from the information needed for those to whom such advice is proffered. Let us have the moral choices of economists upfront. If they have a particular conception of the social good, of the desired end goal of society, they should put that out on the table rather than hide behind vague and unsubstantiated assertions of efficiency and objectivity.

Towards the end of the work, the author very appropriately notes the fact that our current mess of interventionist and regulatory policies were themselves the products of previously hidden collectivist visions, however they may have been modified, here and there, by pro-market reforms. Such a mix did nothing to prevent the current economic crisis in part because of the lack of clarity and uncertainty those policies engendered.

If policy analysts and economists in general would state upfront the world view that informs their particular prescriptions, it would at least go part of the way to providing a better handle on the overall regulatory picture. More information can only help and would constitute a first step in opening up public discussion of something potentially very useful: What kind of society do we actually want?

That is a question better suited to moral philosophy. Hence a return to the foundations of economics as a discipline—a return to first principles. That is a debate well worth having.