Resistance to propaganda is difficult: if we succumb to it or embrace Machiavellian methods, we undermine the humanity of our project.

Edward Bernays: Prophet of “Spin”

In his masterpiece, “On the Nature of Things,” the great first-century BC philosopher Lucretius argued that in a machine-like world made up of atoms, “swerve” or “spin” must be posited as the basis of free will. In the intervening millennia, quantum theory has secured much wider patronage as an account of indeterminacy, and clinamen, Lucretius’ Latin word translated as spin, has assumed the broader connotation of inclination or bias. Perhaps no one in the 20th century took greater advantage of this evolution than Edward Bernays, the prophet of “spin.”

Bernays fancied himself the “father of public relations,” a title he devised and campaigned for throughout his life. His book Propaganda (1928) unwittingly helped to transform this once neutral word denoting something propagated into a term of derision, in the sense of biased or misleading information. Bernays believed that the masses are largely uninformed and irrational, and that it is up to the cognoscenti to harness their herd instinct and crystallize it in forms favorable to their own purposes. Such beliefs have had a significant impact on both American advertising and American political discourse.

Bernays was born in Vienna in 1891, the nephew of Sigmund Freud twice over—his mother was Freud’s sister and his father’s sister married Freud. When Bernays was a child, his family moved to the US. Bernays graduated from Cornell with a degree in agriculture, but his passion was journalism. Bernays worked as a medical editor and press agent before going to work for the Committee on Public Information in World War I, where he was tasked with building public support for the war effort. In 1922, he married Doris Fleischman, who, flouting the conventions of the day, kept her maiden name.

His experiences during the war opened Bernays’s eyes to the manipulability of public opinion. Once the war was over, he opened a public relations business and in 1923 published the book, Crystallizing Public Opinion. Bernays’ campaigns are the stuff of legend—he promoted Ivory soap because it floated; he promoted Dixie Cups by suggesting that non-disposable cups spread disease; and while working for a hair net company, he successfully lobbied for laws requiring their use. Hired to spice up a bland Calvin Coolidge, he invited celebrities such as Al Jolson to a pancake breakfast at the White House.

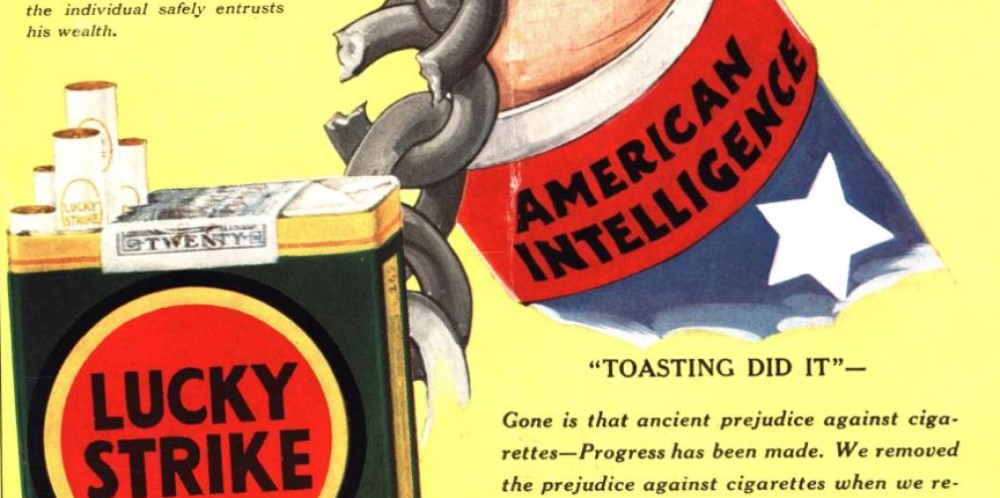

Bernays the publicist had a long association with tobacco companies. The distribution of free cigarettes to US troops during World War I had hooked a large proportion of US males on smoking, but women were reluctant to take up the practice. Bernays began associating cigarettes with a svelte figure, promoting them as a good substitute for sweets. Seeking to exploit the notion that women were oppressed, he promoted cigarettes as “torches of freedom.” He arranged for young women to crash the 1929 Easter Day parade in New York, emerging from houses of worship, lighting up, and proudly joining the procession.

To withstand Bernays’ cynical vision, democracies need fewer manipulable consumers and more citizens worthy of self-government.

Some of Bernays’ efforts took on a more political tone. Hired in the 1940s to promote US banana sales, Bernays arranged for celebrities to appear publicly with the fruit in hand, touting its salutary effects. When his client, the United Fruit Company, expressed alarm at the political situation in Guatemala, raising the specter of the industry’s nationalization, Bernays arranged for the publication of many articles decrying the threat of communism there, even organizing tours of the country for prominent citizens. In 1954, the CIA helped to arrange a coup, during which Bernays functioned as the chief supplier of information to the US press.

Bernays referred to his approach as the engineering of consent:

If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it? The recent practice of propaganda has proved that it is possible, at least up to a certain point and within certain limits.

He likened the production of mass opinion to the mass production of material goods, calling it “the very essence of the democratic process, the freedom to persuade and suggest.” He wrote that the only difference between education and propaganda is in the point of view. To be precise, he said, “The advocacy of what we believe in is education. The advocacy of what we don’t believe in is propaganda.”

Bernays was no advocate for a society of free and responsible individuals, at least not as it pertains to ordinary citizens. He believed that the average person has no idea what to think, arguing that it is up to elites to make up his mind for him.

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government, which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.

As Bernays saw it, a healthy democratic society requires the regulation of the beliefs of the many by the work of an unseen few. Such people understand the principles of psychology and the technology of public opinion. “They pull the wires that control the public mind,” he wrote, and they “harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.” They tell us who to admire and who to despise, how our houses should be designed, what food to serve, how to dress, what sports we should play, what entertainments we should prefer, how we should talk, and even what jokes we should laugh at. Government itself depends on knowing how to get the public to acquiesce.

Doubting that ordinary people possess the ability to think for themselves, Bernays might have relished contemporary political discourse, which often resorts to name-calling and ridicule. Forced to think for themselves, he thought, people could fall back on little more than “cliches, pat words, and images which stand for a whole group of ideas or experiences.” The propagandist needs merely to “tag a political candidate with the word ‘interests’ to stampede millions of people into voting against him.” This use of labels to mold opinion has been amplified in the age of social media. Merely categorizing someone or something as communist, capitalist, woke, or systemically racist is all it takes.

Bernays was unencumbered with even a trace of political or ethical idealism. He was convinced by his uncle’s writings that thoughts and actions are mere substitutes for desires human beings have found it necessary to suppress, that people cannot see things for their intrinsic worth but only as representations of something else, and that virtually no one can bear to face up to his or her real motives. Accordingly, Bernays argued that “no serious sociologist any longer believes that the voice of the people expresses any divine or especially wise and lofty idea.” As a result, the public’s opinion must be fashioned for it, using symbols and cliches provided by propagandists.

Bernays found such notions not only sustainable but immensely profitable. He made a fortune and lived to the ripe old age of 103. His wife, Doris, was not quite so lucky. At the same time her husband was successfully increasing the attractiveness of cigarettes to women, Doris had become addicted to them. Bernays attempted repeatedly to get her to quit, even breaking in half any cigarettes he found around the house and flushing them down the toilet. Later in his life, he would seek to undo the damage he had done, working with public health advocates on anti-smoking campaigns. But his efforts may have proved too little and too late for Doris, who predeceased him by 15 years.

Bernays’ efforts also backfired in another way. One of the admirers of his books turned out to be Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. According to Bernays himself, Goebbels had Bernays’ books in his library and used them “as a basis for his destructive campaign against the Jews of Germany, which shocked me.” Once regard for liberty and responsibility have been consigned to history’s dustbin, there is nothing to stop the technology of public opinion from spinning in any direction its wielders might choose. In a world from which respect for objective truth has been expunged, we are left with nothing but biases and the propagandists who mold them.

To withstand Bernays’ cynical vision, democracies need fewer manipulable consumers and more citizens worthy of self-government. They must care about separating truth from falsehood, be able to recognize spin when they see it, and jealously guard their liberties and responsibilities. Among other things, the development of such citizens would require childrearing and education practices that esteem ends over means, prioritizing knowing and serving the good over merely getting what one wants. One way of fostering an appreciation for the importance of such knowledge is to introduce students to Bernays’ work, inviting them to behold life in the dystopia he describes.